It’s May 2011 and me and my mate are lying side by side on my single bed. We are fourteen years old and Odd Future is everything. We downloaded the mixtapes, watched all the videos – the freestyles, the group antics – we have even made our own spin-off – logo brandished on phone home screens – and we’ve been looking at Supreme clothing, which of course we can’t afford.

We press play on Tyler, the Creator’s debut album and stay silent, lying still.

First we hear from Tyler’s psychotherapist alter ego, Dr. TC, then Tyler’s regular voice irately declares: “I aint a fucking role model.” He’s talking directly to us, we think, and, to all the other fourteen year olds who had ‘discovered’ this subculture online and felt like they belonged to it. I imagine you felt the same way. But his denouncement, obviously, is the hallmark of someone who knows exactly what they are but can’t yet concede.

We were at the perfect age to be indoctrinated. Listening back to Goblin, it is clearly disgusting and singularly myopic for a nineteen year-old to have been rapping about violence, sexual violence, and homophobia in the ways Tyler was, even while acknowledging that this was a performance, as he would so often stress.

I think we were aware that this content was unacceptable, but it seemed murky at the time – or maybe we just didn’t want to own up to the fact. Tyler tried to explain it away by substituting lyrical energies over content: he only used language that “hits and hurts people” the most, he pleaded. “I don’t know, we don’t think about it, we’re just kids”, he continued. Sure.

I’m treading old ground here. Every review of Tyler’s work acknowledges this past. But I think all of Tyler’s then-fans, myself included, have to acknowledge that as much as Tyler has had to, as Ira Madison III puts it, “earn the right to penance”, we have to earn this with him by confronting the fact that by buying Tyler’s music, his brand, we were implicitly condoning his content – however naïvely.

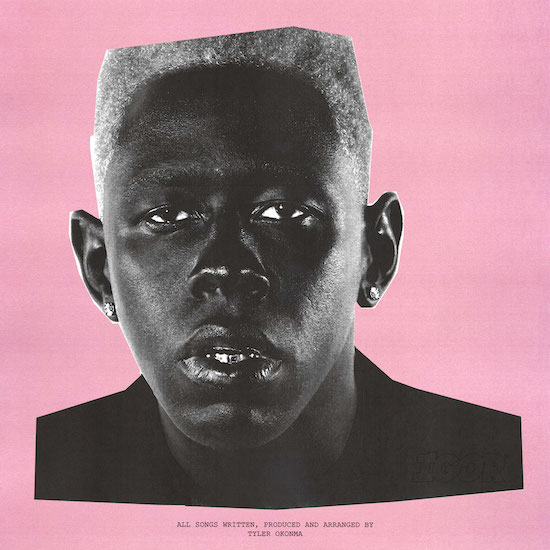

So, IGOR. The opener sets the tone for a new, more concise, direction: the vocals and drums are fluid yet compact, and I’m making toast on the synth line. But if we are, as Tyler has patronisingly instructed, listening “ALL THE WAY THROUGH, NO SKIPS. FRONT TO BACK” – oh, and by the way, “NO DISTRACTIONS EITHER. NO CHECKING YOUR PHONE” – then we soon get treated to IGOR’s two most uninspired tracks back to back. ‘EARFQUAKE’ feels long even at 3:10 as it peddles out a single idea that feels aimless and, unfortunately, no matter how much vinyl crackle is injected, or how many times Tyler says “skate” and “fuck” underneath the beat, character on the verses of ‘I THINK’ is still lacking.

The hooks on these tracks, and elsewhere on the record, are undeniable, however. Tyler’s song writing has continued to progress since Flower Boy and ‘RUNNING OUT OF TIME’ and ‘GONE / GONE, THANK YOU’ demonstrate his ability to deftly abut on hip-hop, pop, and jazz through complimentary shades of convention and experimentation.

My interest is really piqued by ‘NEW MAGIC WAND’, which shows Tyler’s idiosyncratic energy resurfacing: it’s arguably IGOR’s answer to ‘Who Dat Boy’ or ‘Domo23’ but Tyler’s recent productions allow ideas to take a supporting role and not constantly jostle, as they have done on his previous records, for listening space. ‘NEW MAGIC WAND’ consequently arrives with a freneticism that is all the more sinister for its being contained. The teaser video features a blonde-wigged Tyler flailing and a crowd of four or five youths flailing back. My teenage gatherings are nostalgically resurfacing. I think this is what was so appealing about Tyler’s more intense and aggressive productions; they give you a space, even if just for a few minutes, to totally lose your shit. At the end of the video Tyler runs away.

Unfortunately, Tyler’s tedious jilted lover persona returns again on IGOR. There is something cathartic, for sure, about his emotionality on the chorus of ‘NEW MAGIC WAND’. “Please don’t let me down” Tyler pleads vulnerably over the chaotic beat. However, on the same track, Tyler tells us he will “blow the whole spot up” and that his lover’s ex is “gonna’ be dead”. Surely this kind of lyricism isn’t hugely divorced from the kinds of violent imaginings that Tyler began his career with?

The following track ‘A BOY IS A GUN’ explores similar themes from the inverse perspective: “No, don’t shoot me down” repeats Tyler, turning his own violence back on himself, feeling rejected by someone he desires, then requires distance from and continuing to thematise his sexuality as he did on Flower Boy. Maybe the dialectic created by these two companion tracks is why Tyler feels we have to take the record holistically and not pick and choose while we draw conclusions. Of course, we can continue to debate whether Tyler has ‘earned penance’ here.

IGOR closes with Tyler looking for forgiveness, for acceptance: “Are we still friends? Can we be friends?” he sings, tentatively. Maybe he is propositioning the ex-lover that he has alluded to through the album. Or, maybe, the track is dedicated to the Odd Future members who got lost, so to speak, along the way. Tyler reunited with long time friend and collaborator Hodgy – who bitterly referred to Tyler as a “fraud” in 2015 – at last summer’s Low End Theory. Or, (more spuriously still) maybe the track is dedicated to our now Prime Minister who, when she was Home Secretary, banned Tyler from entering the UK in 2015 based on his lyrical content. Recently the ban was lifted: can they be friends after all?

This Sunday, at Bussey Building, Tyler promised an impromptu performance. The queue to get in stretched back to the station. Fans were jumping between roofs to get a view of the gig, and were scaling the surrounding fences. The show was shut down before it had begun. Tyler’s cultish appeal, generated by his intriguing online persona, is clearly still enormous.

When the Home Office issued their ban, it arrived with the possibly quite hyperbolic statement that his work “fosters hatred with views that seek to provoke others to terrorist acts.” Whatever you think of the decision to ban an artist entry to a nation based on the content of their work, that Tyler’s lyrics contained “violence” and an “intolerance of homosexuality” is undeniable. And although protest arrived due to the fact that the lyrics cited were from six years previous, the way in which we consume music is far from linear. Those who discover his work through Igor are more than able to go back to the early material and decide for themselves whether they can tolerate the rank misogyny and homophobia. Tyler’s latest album remains ambiguous and uncertain, however. Or maybe I’m just projecting my nostalgia for an artist that defined a period of time in my life and provided the sense of nebulous, though detached, inclusion.