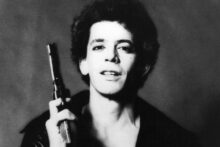

It’s no wonder Lou Reed often got grumpy with those who interviewed him. Whether they were partial to his output or confounded by whatever he’d been up to, journalists constantly urged Reed to explain himself.

This was especially true in regard to 1975’s Metal Machine Music. It was by no means the first example of “noise music” in the history of the human eardrum but it was one of the most notorious and therefore influential. In the immediate aftermath of its release, and then for the rest of Reed’s life and long career, people were determined to figure out his motivations for releasing a double-LP of screeching amplifier feedback.

The star’s comments varied and they could be contradictory:

Reed used Metal Machine Music to help him sleep. He thought it would make a suitable soundtrack for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It was meant to be heard through headphones only, preferably while alone. When Reed broke his own rule and played it in others’ company, MMM’s vibrations brought one friend to orgasm. He didn’t like any of his solo albums with the exception of Berlin and Metal Machine Music. The latter was the closest he had got to “perfection”. People could listen to just one of the sides (which are all the same length, at 16.01, with a locked groove at the end of the fourth side): “there’s no particular need to listen to the others.” It was a calculated attempt at career suicide after the commercial success of Sally Can’t Dance, an album Reed hated. MMM would repel all those “fucking assholes” who attended his concerts and yelled out requests for ‘Vicious’ and ‘Walk On The Wild Side’. It was intended as his grand final statement. He was “trying to do the ultimate guitar solo.” The music was “one machine talking to another”. It was a serious work of art (“… I was also stoned”). He had, so he said, been working on it for six years. It included frequencies that were against the law (“…they use them in surgery”). It was supposed to have been sold with a “Warning” sticker on the front which would have signalled its contents more clearly than the relatively mild subtitle: An Electronic Instrumental Composition. It was the most returned LP in record shop history. Nobody Reed knew had listened to it all the way through, including himself. The liner notes, which contained that latter claim, were meant to be taken with “a gallon” of salt.

“I thought people would love it,” Reed said in 2004.

Well, some did. More and more of them, over the years, whether you consider them all to be aural masochists or else contrarians who would secretly rather be listening to Transformer.

MMM’s reputation was enhanced by those who defended it and paid tribute to its audacity. Sonic Youth’s 1998 Silver Session (For Jason Knuth), for instance, has been likened to a cover version of Metal Machine Music. Reed wasn’t mentioned in Silver Session’s liner notes and Sonic Youth’s effort was edited down to a comparably brief and more forgiving running time. Still, it contained the familiar sound of guitars and amplifiers feeding back on one another, with no vocal or rhythm to hold anything down.

The sticker on this compilation could not make matters much clearer, so returned copies ought to be at a minimum: “[A] New collection of extreme sonics inspired by Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music”.

The first cut is provided by the ex-Sonic Youth cacophony enthusiast himself, Thurston Moore. Titled ‘Drone Cognizance’, it is an intentionally “guitar centric” homage to MMM. As Moore explains in the accompanying booklet, he was interested in Lou’s blueprint as a source of inspiration and had confidence that his fellow contributors would avoid “slavish recreation”. ‘Drone Cognizance’ was made using twelve detuned Fender Jazzmasters, serrated drumsticks, cylindrical files, a violin bow and one pencil. It is anchored by a low-end drone, around which swirls the spikier disorderly feedback. The result resembles Glenn Branca blaring from a half-tuned radio. There are no drums, appropriately, yet its implied tempo is quick-feeling, and the thirteen minutes fly by nicely.

On Side B, Aaron Dilloway uses a sample from Reed’s MMM and loops multiple cassette decks in a way that proves, at first, to be piercing and pestiferous. As the layers grow denser and subsequently more ambient, the experience becomes increasingly suitable for isolation tank relaxation. Perhaps this mirrors the way receptions toward the original album turned gradually warmer.

In the notes, Margaret “Pharmakon” Chardiet imparts that “Music is math” (i.e. finite; organised) whereas noise is “wrangling chaos and pure energy”. Her piece has a bass-y throb – imagine a child irreverently thumping a key or five on a church organ – with broken equipment squealing in accompaniment. In a manner of speaking, it could be a cyborg’s imitation of the bagpipes. It ends in a locked groove so its length reads as “06:03 or ∞”.

Striving to be “faithful to the spirit of the original even though techniques were very different”, Drew McDowall (Psychic TV, Coil, etc.) offers the calmest and most soothing provision with his straightforwardly named ‘Feedback’. This moment, in particular, emphasises that noise music can provide tranquil respite from our blaring, overwhelming, hyper-digital surroundings. ‘Feedback’ is followed by Mark Solotroff’s ‘Terminal ’25’, the second fairly placid number on Side C. It’s on this side that listeners could be forgiven for mistaking Power To Consume, Vol. 1 as more of a tribute to Nurse With Wound’s blissful Soliloquy For Lilith.

The final side is filled by Sam Mckinlay, aka The Rita. ‘109 190’ is a splintering, crackling, monolithic roar. It comes as little surprise to learn Mckinlay has utilised recordings of a restored World War II air fighter engine and taken his cues from the mid-90s harsh noise scene. As such, ‘109 190’ recalls Vomir’s distillation of Merzbow’s sonic aesthetic in the sense that you can nip into the kitchen, boil the kettle, make a cup of tea, nibble a biscuit and return to exactly what was going on when the thirst kicked in.

Mckinlay’s is the ugliest and least pleasant track on the compilation. This means the worst has been saved until last… Or is it the best? It depends on your viewpoint and tolerance for a wall of barely changing motor rumbling. If it is the least enjoyable, then maybe it’s the one that’s closest in spirit to Reed’s initial provocation. That point also hinges on what Reed’s motives were in the first place.

One thing’s for sure. As attested by this anthology’s cross-generational collection of openminded (and open-eared) artists, the legacy of Reed’s most infamous opus isn’t going to fade out anytime soon. That groove remains locked.