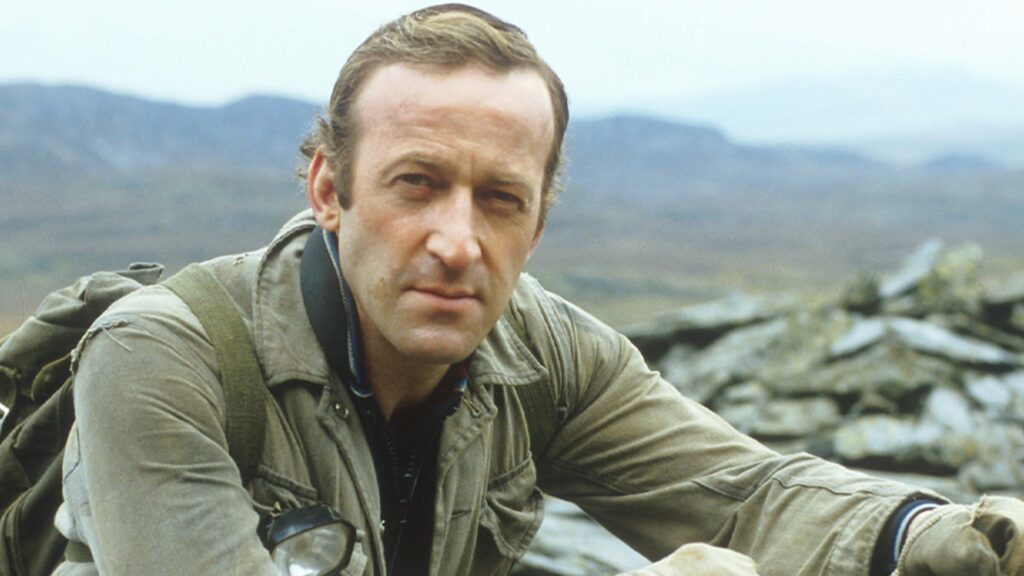

One wet Autumn night, a photograph of a young woman appears on my Instagram feed. “Back in the day, I worked on Edge Of Darkness,” her post begins. I’m taken back to Bob Peck in the rain, Joanne Whalley in his arms, small black flowers on hillsides, and one of the BBC’s most extraordinary series, currently back on BBC iPlayer to mark its fortieth anniversary.

Forty Autumns earlier, Val Harris (née Turner) was the production assistant on a six-part drama that still defies classification and convention. Edge Of Darkness is a revenge thriller, a mystical nuclear-and-environmental-apocalypse fable, a clear-eyed political document of the mid-1980s, a ghost story. It fittingly aired at the end of a year that included the Battle of the Beanfield, the end of the miners’ strike and continued IRA bombings. It fittingly aired at the end of a year that included the Battle of the Beanfield, the end of the miners’ strike and continued IRA bombings. It foregrounded realism in its use of news footage of police aggression and of Thatcher, cameos for TV presenter Sue Cook and Labour MP Michael Meacher, and references to politicians like then Secretary of State for Defence Michael Heseltine. It also mixed in formal, surreal experimentation. How many of us have imagined talking to the dead, as happens throughout, if they are walking right next to us, bright and alive?

It proved so popular on BBC2 in November 1985 that BBC1 controller Michael Grade repeated it on the main channel the week before Christmas (doubling its audience to eight million viewers). Edge Of Darkness’ success speaks of a time when the public service broadcaster had the guts to commission a drama which connected profoundly with social unease, while also being deeply weird.

I arranged to meet Harris, who lives not far from me; she is effusive and generous, sharing details about Edge Of Darkness‘ lively team. The central, whirling cog was veteran writer Troy Kennedy Martin (Z-Cars, The Italian Job), who would dictate scripts to Harris the night before they were shot, which she’d type up on his Olivetti typewriter. Late in the shooting she had a car accident, and had to beg a police officer to take the blood-stained copies to set while she went to hospital. “The show must go on,” she wrote on Instagram. Then there was producer Michael Wearing, who had previously made Boys From The Blackstuff, and went on to make Pride And Preudice and Our Friends In The North in the 1990s. Harris says he ended up physically fighting with Kennedy Martin during the shooting in London, frustrated by his working methods, although they quickly made up. There was the director Martin Campbell, known as Zebedee, due to his bouncy enthusiasm, who’d go on to direct two Bond films, both featuring American actor Joe Don Baker in a similar CIA agent role. And there was cinematographer Andrew Dunn, who a year earlier, had worked on the BBC’s other nuclear classic, Threads.

The series also skyrocketed the career of Joanne Whalley as Emma, the murdered activist daughter of policeman Ronald Craven, played by the extraordinary Bob Peck, who, Harris confirms, got the role thanks to her and location manager Alison Barnett. Director Martin Campbell wanted the then-little-known actor Jim Broadbent; Michael Wearing wanted Tom Bell, the British 1960s New Wave cinema actor who later found success in Prime Suspect; Kennedy Martin wanted Bernard Hill. “They were all quite alpha male men, and they all wanted someone different – so Ali and I came in and somehow convinced them – with a pincer movement.”

The women had seen him in Macbeth with the Royal Shakespeare Company – he was a theatre actor who had never done TV before. Were her superiors happy in the end? “Oh my god, yes. When we’d seen Bob in theatre, we were, oh my god, that’s him – he had the grittiness, but the softness needed for the part”.

Peck’s face – pale-blue eyes, aquiline nose, bleakly handsome – nails his character’s grief-filled fragility, and his hard-boiled policeman’s rage. That face is our guide through a story that begins with trade union election fraud in a dimly-lit hall (it’s almost always dimly-lit in Edge Of Darkness, unless we’re in institutional daylight, smothered by dull greens, beiges and creams). Then the story starts unravelling and exposing deeper, gnarlier roots.

Craven’s daughter is chairing a meeting with her “comrades” from college; Dad picks her up and takes her home; they talk about him fancying her friends; they acknowledge his desire for sex. Sex continues to be present after Emma’s death on the same night, as her dad wanders around her bedroom in a long, speech-free scene, to the sound of Willie Nelson’s ‘Time Of The Preacher’ playing on Emma’s turntable. He looks through her things, finds and then kisses her vibrator, although he does so gently, as he would the cheek of a baby. Other detritus of Emma’s short life surrounds him: toy clowns, seashells, postcards of trees that foreshadow her lately, ghostly speeches, and a box decorated with a pink background and white clouds, scrawled over in marker pen with a four-letter word: Gaia.

The Gaia hypothesis of James Lovelock, which states that the Earth self-regulates after destruction, swirls mysteriously through the plot and names a group with which Emma was involved. The story’s multiple elements are revealed carefully, its tone foreshadowing the slow-burning TV that came to life in the age of streaming.

As well as trusting its viewers with the complexity of its plot, much of the making of Edge Of Darkness was also audacious. It pioneered the use of Steadicam in its first episode, following Peck from his hotel room in the lift, through the foyer, down the stairs to a basement garage to meet shadowy government attaché Pendleton (played by Charles Kay: “Charles was terrified he’d mess up his lines and we’d have to do the whole take again”). Harris also remembers the building of “a James Bond set” down a mine: “We got lost down it one Saturday morning – it was terrifying.” Plus the way Baker was eventually recruited on his way to film in Malta, changing planes at Heathrow Airport. Director Campbell had loved him as a crazed mob enforcer in Don Siegel’s 1973 neo-noir, Charley Varrick, but didn’t have the budget to fly to the US to convince him. “Then his agent rang. He was at the airport for a few hours, so three of them rushed down from our office, and showed him the script. He immediately said yes.”

The commissioner of Edge Of Darkness, the BBC’s then-new Head of Drama Series and Serials, Jonathan Powell, didn’t come to the set once, Harris adds, because “he trusted us”. She rings him on her mobile as I drink my coffee: he became BBC1 controller a few years later, and a few days later, we speak on the phone. Edge Of Darkness got commissioned in the first place, he says, because ITV drama was riding high after the success of Brideshead Revisited and The Jewel In The Crown. “That was a kind of knife to our heart, because these were big classic novel adaptations, the stuff we were meant to do well. So my job when I started was two-fold: to launch popular long-running series, and restore’s the BBC reputation for quality.” In his first few years, he launched EastEnders and Casualty, long-running dramas that are still running. “And our reward, so to speak, was to be given freedom – not to experiment so much, but to take risks, and do proects we considered interesting.”

Before his promotion, Powell had produced the Alec Guinness-led Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979) and Smiley’s People (1982), and worked with Kennedy Martin on a 1983 adaptation of Angus Wilson’s nuclear war novel, The Old Man And The Zoo. “Troy had been in despair at the lack of imagination – and politics – in new narratives on television,” he remembers. “So when I got my new job, and said to him, ‘Troy, have you got anything that you want to do that you don’t think anybody will do?’ He said, ‘Oh, literally, as it happens, I have.’”

Powell’s reward led to him becoming emboldened, it turned out. “It was something Troy thought that would never get made. I was very proud of that at the time, running the drama department and being in the BBC with Thatcher… You felt as if your back was absolutely against the wall. If you had an executive position in the BBC, with the press and the government, you could feel the heat. They’re feeling the heat now, but even in those days, you really felt the heat. So these projects came out of what we perceived to be a difficult situation, but I could make things which in normal circumstances, I would not have been able to, or possibly not have had the courage to.”

After Edge Of Darkness, Powell worked with another working-class writer, Dennis Potter, on The Singing Detective; giving opportunities to striking voices to him was key to the BBC regaining its reputation. “Dennis and Troy had grown up with television. They were writers who were pushing and experimenting with the boundaries of television, and that’s what I was really interested in.” He also liked the idea of writers being novelistic in their narrative scope”. Like The Sopranos and The Wire were of the turn of the century, I ask. “Yes, indeed. All the great American series are generated by writers.”

Television drama was also moving away from being made in studios to being made on film, Powell adds, allowing directors more “scope and scale of the narrative you could tell”. Because the film was on rolls, he often only saw rushes occasionally. “Essentially, you saw nothing until you saw a final cut.”

Kennedy Martin had wanted something particularly bold for the series’ original ending: Bob Peck turning into a tree. Time has muddied people’s recollections of what happened. “I know there were questions about the technical problem of how we could do this convincingly, without people laughing,” Powell says. “Then there’s another version of the story which has Bob Peck saying, ‘I’m not turning into an effing tree.”’

A few days later, I speak to Edge Of Darkness location manager Alison Barnett, with whom Harris is still a close friend; later, the producer of Life Of Mars and Broadchurch, she’s just finished work on big-budget Netflix series House Of Guinness. She remembers travelling 14,000 miles across the country by car, and finding Craven’s nature-surrounded house, in deep countryside near Ilkley, North Yorkshire: “It was owned by a lovely couple who were in their late seventies, early eighties, who let us film there for a month.” And she remembers collecting the American actor Baker herself from Leeds train station: “He was this huge presence coming down the platform in his stetson and cowboy boots.”

She remembers the ending being controversial. “The whole coming together of Gaia and Troy’s beliefs was quite tricky to get around, and he didn’t turn into a tree, but we did it in the end.” The black flowers that grow on the land were Troy’s idea, she says. “I think we had to go back and reshoot that in the moment with snow.”

Kennedy Martin died in 2009; the black flowers are linked again to James Lovelock’s ideas of the world rewilding itself after a mass extinction event. “It’s happened before, you know,” says Emma to her father in the last episode. “Millions of years ago, when the earth was cold, it looked as if life on the planet would cease to exist, but black flowers began to grow, multiplying across its face until the entire landscape was covered with blooms.” A cold earth in 1985 would suggest nuclear apocalypse, which sits nicely against the series’s explorations of plutonium. Our Earth today is rapidly warming, but the strands of industrial and political corruption in this series still speak to our contemporary world, as do the eternal experiences of love, death and grief.

Barnett still keeps Edge of Darkness on her CV. “It’s the production people always want to talk to about,” she says – and one that reveals what happens when commissioners embrace the spontaneous, innovative creativity of their writers and crews, and trust their audiences to come with them.