In 1990, the final serialised chapter of Masamune Shirow’s The Ghost In The Shell (攻殻機動隊) was published in Kodansha’s Young Magazine in Japan. The manga, a seinen title aimed at young adult men, was the third major work he had completed across the 1980s. Shirow (a pen name, for the author Masanori Ota), had created a series of densely textured, often technologically inspired and politically engaged, speculative manga including Appleseed which was awarded the 17th Seiun Award for Best Manga in 1986.

At the time of publication The Ghost In The Shell was well received, but its reception in no way predicted the flood of cross media that would spring forth from the manga. A large amount of this success can be attributed to the Mamoru Oshii’s film Ghost In The Shell [GITS] which this month celebrates its 30th anniversary. Like the manga itself, the film’s initial reception in Japan was modest, but it found a strong and growing resonance in North America, Europe and countries including Australia where its continued longevity in popular cultural memory is matched by only a few anime of that era, such as Akira.

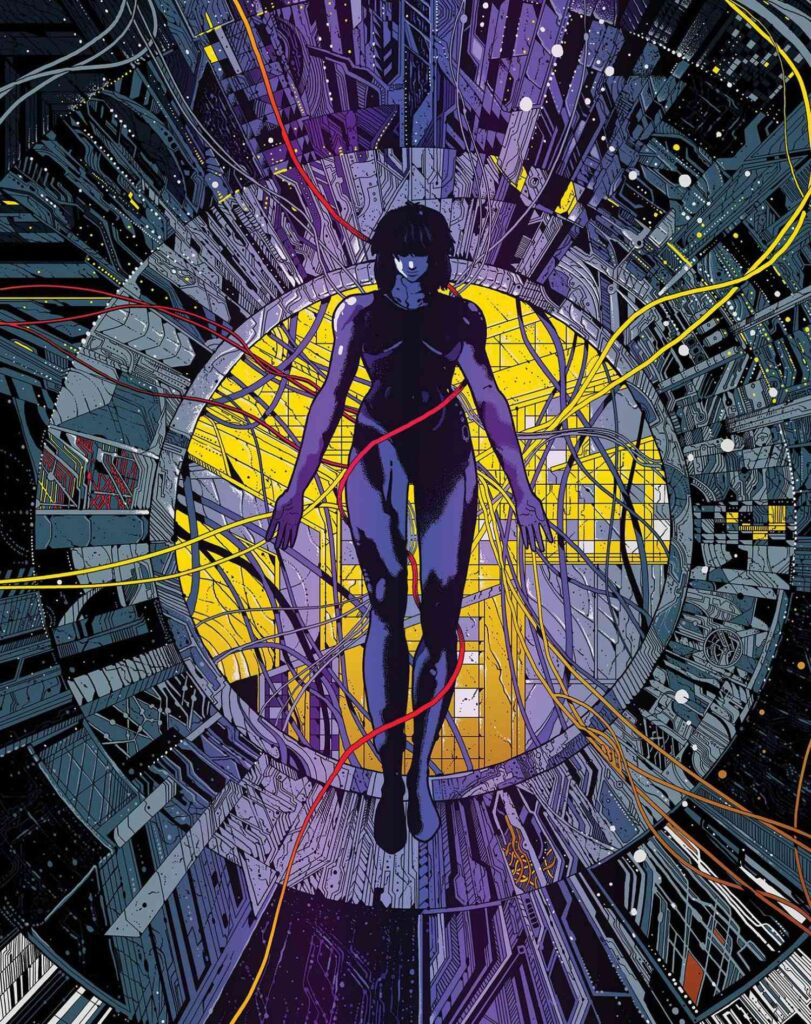

The film version of GITS unfolds in 2029, in New Port City and is told through the lens of protagonist Motoko Kusanagi, a full body cyborg who works alongside several other partial prosthetic and human agents as part of an extra-governmental counter-cyber terrorism unit called Section 9. While investigating a cyber-hacking entity called the Puppet Master, a chasm of political espionage opens out and reveals the Puppet Master to be an escaped government experiment, known as Project 2501, that has evolved and emerged as a new form of sentient life, from, and through the web.

In a narrative sense, Oshii’s GITS is remarkably streamlined when compared to the manga. Philosophically though it feels more nourished, and calls upon both a cartesian and Shinto reading of existence, seeking to unpack concepts of duality, of transhumanism and to understand the technologies and machines that increasingly become our primary interfaces with each other and our world. As Shinto exists without a dominating sense of eschatology, the fluidity of movement between the real and the virtual is deeply tangible in GITS and forms the dominating focus for the film.

While Oshii’s strips each of Shirow’s characters to an essential core (their ghost if you like), he does so in a way that not only creates a more deeply invitational approach to characterisation but also embraces the weight of interconnectedness of being that haunt so many of the film’s players. Oshii asks us to insert ourselves into some of the static, the greyness of being, and in doing so creates a very human connection to a Kusanagi, a protagonist who could otherwise come off as distant and perhaps even hostile.

Oshii also manages to create an entirely lived-in world and it’s this intricacy of world building – one that encompasses both visual and audio environments, as well as the non-diegetic sound world – that is perhaps responsible for GITS’ lasting success as a franchise. “For me,” Oshii remarked when interviewed at the Toronto International Film Festival, “I have to think about the world first, I have to think about the world within which the story takes place”.

Intentional or not, Oshii’s thorough visioning and commitment to environment, to architecture, to light, to weather and ultimately to the detail of being, is truly one of the most compelling aspects of his approach to animated film storytelling. A large part of GITS’s visual depth can also be attributed to Art Director Hiromasa Ogura. Having worked with Oshii across numerous projects in the late 1980s and into the early 1990s (including both Patlabor films), Ogura’s capacity to envision rich and immersive settings from often abstract source materials is evident from within the first moments of GITS.

“When we were starting to work on Ghost In The Shell” Ogura says, “one of the first things we did was to go to Hong Kong for location scouting. It was a kind of research trip, and something that was a little bit unusual at the time. Haruhiko Higami, who was taking location photos in black and white, a lot of his photography was very important for the concepts of the design. I was also taking photos during my time in Hong Kong.”

These photographs Ogura shot on film, which were colour, contained in them something more than the uniquely cluttered and chaotic colonial sprawl that was Hong Kong in the 1990s. They also captured a curious by-product of Hong Kong’s climate which would ultimately go on to become central feature in the visual aesthetic of GITS.

“When you think about Hong Kong, it’s often the neon lights and the sense of chaos in the streets, you don’t always think of the weather. In Hong Kong it’s very humid, and hot. So often you are coming into air-conditioned spaces and then going back out into this strong humidity.

“One time I had been inside a building with my camera, and I came out and shot some photos, and when I developed them, the lights in the streets had this aura around them. The humidity had caused the camera lens to fog a little, and in doing that there was this diffusion of light. That feature was something that really affected me and it was something that I ultimately brought into the way I approached part of my work in Ghost In The Shell.”

Unquestionably, the quality of light and striking visual perspectives of many scenes play a subconscious, but utterly critical role in shaping the believability of New Port City. Much of the films’ action unfolds in the neglected spaces between the old town and the new city. Through Ogura’s work with colour palettes and texturing he creates a very discreet language, one of density and visual intensity which ensures film’s suspension of disbelief is never interrupted, no matter how radical the scene’s settings might become.

“The colours I worked with, they started with my memories of Hong Kong,” Ogura notes, “I started with the sense of colour that was in that city itself, but gradually I found ways to use colour to create something very unlike what I had initially experienced. Usually this was a process of changing the base colour and then another detail and another, and so on. Oshii-san seemed very happy with the process for the way we built those places, so it stuck. He encouraged density and detail, to have texture that almost felt like too much, but it added a very strong feeling to the locations.”

This approach of pushing the visual density, the contrasting of light and dark, saturation and atmospheric static, is deeply evocative and invests much of the film’s locations with a certain seimeiryoku, or vital force.

“With many of the settings in the film, I’d often try very radical things. In the opening sequence, there’s a dramatic contrast between the new city, it has this glowing darkness, and the interior of the hotel where the first scene plays out. The hotel room is a kind of space where you might expect more muted colours, but I knew I wanted something different, something unexpected. So, the colour scheme and also the layout of the room, with the fish swimming in the tanks, was something that took sometime, but I kept working at it. When I showed Oshii-san this, at first, he was a little shocked I think, but before long he was very excited about it and that was how we proceeded with much of the project”.

One of the markers that sets Mamoru Oshii apart from his peers is his willingness to allow place to speak for itself. From the seasonality captured in his works, like the first two Patlabor films, to the otherworldly environments of Ghost In The Shell 2: Innocence (all projects in which Ogura was also involved heavily) and even the fantasy scapes of his Angel’s Egg, Oshii’s attention to place, and allowing it to be a player in the story, gives as much voice to world building, as he does to characterisation. This attentiveness and patience for place, allows us to settle deeply inside a worldview that is often simultaneously familiar but unerringly alien.

Attentiveness and patience are also guiding principles in the musical score for Ghost In The Shell. Oshii’s work has been deeply shaped by his almost four-decade collaboration with composer Kenji Kawai. It could be argued that the soundtrack for GITS has enjoyed similar recognition to the film itself. Kawai, who often describes himself almost as a craftsperson rather than an artist, unlocked a profoundly iconic sound with the score for GITS, but it was a sonic atmosphere born of restrictions.

“For each film we have worked on together,” Kawai explains from his studio in Shinagawa, “Oshii-san offers me some idea to start things, or perhaps some type of limitation. For example with Patlabor 2, he wanted the score to have a strong contrabass sound. For me, rather than having a full orchestra where you have strings and piano, and therefore all these instrumental options, I much prefer when there’s a limitation or a focus for the possibilities of the music.

“This was the case when we started Ghost In The Shell. When Oshii-san and I began talking about the music for the film, the first thing we spoke about was a kind of percussive approach, but it wasn’t to be something instantly recognisable, like a folk instrument. Oshii wanted the score to avoid that sense of the instrument being ‘identifiable’, so we went to an ethnic musical store in Ikebukuro, and bought about four different drums and percussion instruments. I experimented with them, but I realised this wasn’t enough to build the score as I imagined it”.

It was in this moment that the core tenet of what would become the GITS sound world began to unfold for him.

“With just the drums there was this sense of ‘spread’ in a particular way, but for me I couldn’t find the depth to the sound I was looking for. I started to think about what it was I might be able to add to the score to get that depth. Around that time, we had heard the Bulgarian Women’s Choir and that inspired us to think about this use of a choral section. In fact, I contacted them and enquired if they might be interested in working with me on the composition for the film, but they explained to me that they were strictly a folk musical group at that time, and they weren’t able to work outside of that tradition.”

Rather than abandon the choral idea, another project Kawai was simultaneously working on happened to suggest a method for utilising Japanese vocal techniques and traditions, rather than those of the Bulgarian Women’s Choir.

“During the same time as Ghost In The Shell, I was working on another soundtrack for [anime television series] Jūsenshi Garukība, and I was tasked with making a kind of folk music for a scene involving Ondo, a type of traditional dance. This music has an element called Ohayashi, which are like high pitched female vocal interjections, and I started to think that if I used this vocal style as a type of chorus it could be very interesting for GITS. I invited these singers to the studio to record some ideas and it turned out to be quite cool and sounded just like I had imagined it might.

“Anyway, going forward with the idea, and given we were now working with Japanese singers, we were obviously thinking to use Japanese language, but again we didn’t want it to be so identifiable or readily familiar. Instead of using modern Japanese, we decided we could use an older form of the Japanese language, one that you might find in classical texts like the Man’yōshū [Collection Of Ten Thousand Leaves] or the Kojiki [An Account Of Ancient Matters]”.

That text, a short libretto scripted by Kawai himself, became the central refrain for the entire film and translates as:

Because I had danced, the beautiful lady was enchanted

Because I had danced, the shining moon echoed

Proposing marriage, the god shall descend

The night clears away and the chimera bird will sing

“When I wrote the words for those pieces,” Kawai continues, “it was something I hadn’t really done before, but there was no one else to do it, so I just had to. It meant that I ended up going to the library to look through old texts to find a way of using language that shared this ancient form, but also spoke to the nature of the film’s themes”.

Striking a balance between ancient poetics and tying deeply to the film’s core relationship between Kusanagi and the Puppet Master, Kawai produced one of the most easily recognisable musical scores in anime history. Its strength was reinforced in the film by its use in a michiyuki sequence.

Michiyuki, which traces a line through classical literature, Bunraku, Noh and also Kabuki theatre, is a scene where the character travels or shifts between locations or environments, and in the case of films this passage is generally set to music. As a cinematic convention it has played a significant, if not somewhat commercialised role in Japanese film. For Oshii, who typically maintained a problematic relationship with the filmic technique, Kawai’s score created a moment of in-betweenness, a chance to deepen the world within which the characters exist and to create a Ma – a negative space or perhaps even void, which may suggest deeper significance.

He adds: “In essence the world view that is held in Ghost In The Shell is the Shinto world view and so if you go to a Shinto shrine, a jinja, this idea of Ma is of utmost importance, so this was something I wanted to bring into the score. In between the hits of the drums or the ringing of the sleigh bells, I wanted there to be that space, that sense of Ma, so that people could listen deeply into the music. If that in between space wasn’t there, then the atmosphere of the music was at risk of getting buried or lost. This space, and the way in which I used electronic sounds like pads, was a way of creating a kind of landscape in the music”.

That notion of landscape, carved in characterisation, in light, in the real and virtual realms, and in music continues to unfold to this day. Only a matter of months ago a new anime based on Shirow’s original The Ghost In The Shell was announced and an exhibition celebrating his legacy is currently running at the Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo.

GITS’ continued relevance is not exactly surprising. Collectively we find ourselves in a moment that is something of a distorted mirror to the film itself. We have never been better equipped to access information and to grasp the fullness of a virtual realm, but at the same time we seem to refuse, or perhaps are incapable of appreciating the complexity and ambiguity that this data might produce. We barely know the questions to ask of the vastness of the web and moreover what we want from the machines and even ourselves as we push into the unbounded virtuality of the 21st century. The murmuring of the future is eternal and within that haze of possibility, our ghosts continue to whisper.