A few years ago, I caught Patti Smith at Rewire, the Dutch experimental music festival. It was not my first encounter – I’d attended her concerts before, including in my hometown of Cardiff and once in Amsterdam, where she prowled into the front row, sermonising like a preacher, fierce and familiar. Then, as in this instance, I thought I knew what I’d find: her indomitable public persona – that New York drawl, the ragged poet brimming with gravelly charisma. But this time, it was different.

She stood in The Hague’s vast Amare dance theatre, together with her bandmates, the Soundwalk Collective, bathed in flickering light and shadow. Behind them, clips from Salò, Or The 120 Days Of Sodom played across the screen – Pier Paolo Pasolini’s final film, which depicts fascism through scenes of ritualised sexual violence. The writhing bodies, the ambiguous brutality, the overripe decadence charged the air, awakening a sensuality in her spoken-word that splintered in echo, static, and sampled gasps.

“He spread his naked arms to the sun… and he believed he could do anything” she whispered through oozing layers of drone. Then, a rupture: a lash of rhythm, a strummed guitar, her voice became breathy, urgent – “ugh… alright, ugh, ugh ok” – describing her body: her belly, flesh, and “silk stockings”. Moans, groans, fragments of ecstasy. Channelling Pasolini’s legacy of sadomasochism and perversity, Smith transformed into a vessel for erotic transfiguration. Part witness, part oracle, part seductress – a presence that cracked open.

It was after this concert that I noticed the tension pulsing throughout her work. After all, nowhere is this exploration (and explosion) of the death drive – the pursuit of pleasure amid extinction – more pronounced than on Horses. The album serves as a eulogy of sorts, particularly through the closing track, ‘Elegie’. Recorded on the fifth anniversary of Jimi Hendrix’s death, the song was intended as a tribute – not only to Hendrix but also to other recently departed musicians like Brian Jones, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison. Smith’s unwavering vitality lies within this litany of loss – in both juxtaposition and defiance of it – turning mourning into movement, piercing death with lust.

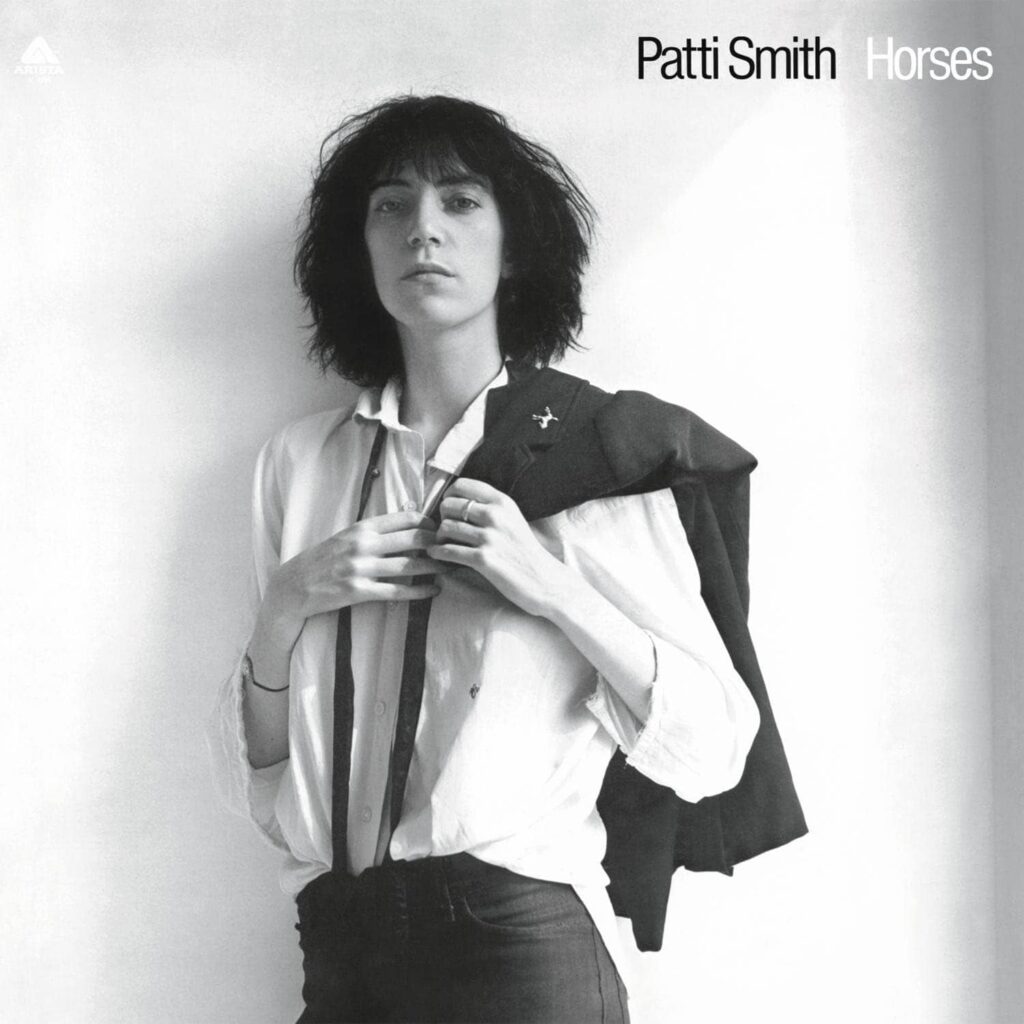

Horses is celebrated as a punk landmark – cool, defiant, steeped in literary myth. But its power also comes from a deep eroticism, one that doesn’t merely mimic the machismo of the male Beat poets and rock heroes, which Smith counted as peers and luminaries, but bends and reshapes it into something more fluid, vulnerable, and untameable. On the record, the literary stylising of her muse, the 19th-century French poet Arthur Rimbaud, mingles with a raw sensuality that channels both queer and androgynous intensity. Revisiting Horses, we find not just rebellion, but wild, unbridled desire – urgent, corporeal, and impossible to contain.

From the very first chords, this is set in motion – ‘Gloria: In Excelsis Deo’ is an expanded rendition of the Van Morrison 1964 original, first recorded with his band Them. Intertwining her own poetry with the original lyrics, Smith asserts her freedom, describing the track as a youthful manifesto on liberation. The opening line, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine”, taken from her 1970 poem ‘Oath’ builds on a reimagining – and rejection – of Christian morality. Raised in a Catholic family, Smith subverts inherited structures of guilt and doctrine, recasting them as tools of self-determination.

This sense of autonomy is hammered home in the chorus, where each letter of G-L-O-R-I-A is chanted with escalating intensity, alongside the fierce repetition of “me, me” which lands in time with the pounding drumbeat. While the song can certainly be read as an expression of same-sex desire – with its gender-switched protagonist drawn to a seductive, commanding woman – Smith’s insistent use of the first-person suggests something more expansive. When she sings, “You were so good, ooh / oh, you were so fine […] here she comes / here she comes”, she could just as easily be talking about herself, collapsing subject and object – the one who wants and the one who is wanted. Attraction here is both inward and outward, performed and possessed.

These themes burst into flame again on ‘Break It Up’, co-written with Tom Verlaine of Television. Said to be inspired by a pilgrimage to Jim Morrison’s grave in Paris, the song explores the urge to escape, to be released from the confines of the body. The imagery is physically charged: a figure trapped in stone, struggling to take flight. Musically, ‘Break It Up’ is muted – a piano riff and mournful progression create space for the vocals to surge forth, beginning restrained, before erupting into a full-blown, cathartic wail. On ‘Birdland’, structure unravels entirely – the track unspools as a freeform improvisation inspired by Peter Reich’s memoir A Book Of Dreams, in which he recounts the death of his father, the controversial psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. Stammering, trance-like, moving from plea to delirium – it’s here that her lyricism is at its most unbound.

Smith’s instantly recognisable voice is untrained and uncontained. On Horses, this intimate instrument howls, breaks, and becomes animalistic. Her vocal delivery ranges widely – from a whisper on ‘Birdland’, to the twang of ‘Free Money’, to the climax of ‘Break It Up’. Pitched in a lower register, fluctuating between the traditionally feminine and masculine, its resonance resists categorisation, allowing her to inhabit multiple personas: the lost child, the fevered priest, or – as with ‘Kimberly’, dedicated to her younger sister, “the babe in my arms” – the watchful mother.

Within this, there is an erotic charge. This is not a voice of smoothness or seduction, but of fervent physicality. Guttural and gasping, her vocalisations draw on excess. She reaches words that are not quite language – sighs, murmurs, exclamations – and these words are erotic because they bypass “the rational” and go straight to the sensual. These pre-linguistic or extra-linguistic expressions carry affect, not meaning – they speak to the body, not only the mind, which is what makes them sensuous. Roland Barthes, in The Grain Of The Voice, writes that the pleasure of listening to a voice isn’t about understanding, but about hearing “the grain” – the texture, the friction, the presence behind the sound. He describes this as almost tactile, like physical touch. A crack in the throat, a breath snagged in the chest, can feel as close as a hand on the skin.

Smith’s vocal style additionally draws from the ecstatic crescendos and emotional urgency of gospel-tinged soul music, echoing the fervour of artists like Little Richard and Smokey Robinson. Black musical traditions run through Horses – the blues from which rock derives, the reggae-inflected rhythms on ‘Redondo Beach’, and the jazz phrasing that colours ‘Elegie’. Smith was also influenced by Janis Joplin, another frontwoman celebrated for her intense delivery. Cast as the “racy hippie” who, as it was popular to say in the 1960s, was a “white girl who could sing like a Black woman,” Joplin was racialised in ways that Smith was not. This fetishisation reveals the racist logic that has long framed Black women’s presence in music – their voices heard as excessive, their expressiveness hypersexualised. Joplin’s vocal potency was interpreted through a lens of unruliness and eroticism; to sound “Black” was, in the cultural imagination, to be “wild” or sexually uninhibited.

Perhaps because of her deliberate self-placement within a lineage of male artists like Ginsberg, Dylan, and Rimbaud, Smith largely sidestepped the sexualisation and exoticisation that marked Joplin’s reception. Her persona was cerebral, even ascetic – aligned more closely with a nascent avant-garde literary tradition, or what she called ‘rock poetry’. In fact, for years, I assumed that ‘Land: Horses / Land Of A Thousand Dances / La Mer’ was a nod to Peter Shaffer’s Equus, the 1973 play in which a teenage boy’s pathological obsession with horses turns from erotic fascination to bloodbath. Yet, it seems likely they share no explicit connection beyond a thematic overlap.

Shaffer’s Equus alludes to a Freudian reading of horses as signifiers of male power and virility. According to psychoanalysis, dreaming of horses is a sign of phallic fixation. In the play, the creatures are literalised as gods, both worshipped and feared. A similar charge pulses through Land, where we encounter ‘Johnny’, who, after being assaulted – his head slammed into a school locker – is launched into a hallucinatory state. Surrounded by “horses, horses, horses, horses,” Johnny is overtaken; encircled, his mind flooded with psychedelic scenes. These equine visions open a window – a doorway to freedom:

There’s a mare black and shining with yellow hair,

I put my fingers through her silken hair and found a stair,

I didn’t waste time, I just walked right up and saw that

up there – there is a sea

up there – there is a sea

up there – there is a sea

the sea’s the possibility

In this imagining, horses are not masculine, but feminine, sensual; a stand-in for wildness, a portal into a dreamlike interiority. Here, Smith takes up Rimbaud’s notion of the “derangement of the senses” – the idea that sight, sound, and perception must be disrupted or intoxicated in order to reach new forms of consciousness. Through this lens, Johnny’s visions become less a breakdown than a breakthrough: a journey toward transformation.

Riding atop a chugging rhythm section, the band generates a tense, looping groove. The taut guitar stabs and driving bass hammer forward with the urgency of hooves, building tension in repetitive cycles, as if chasing something just out of reach. With the cried-out line, “Oh, pretty boy, / Can’t you show me nothing but surrender?”, I am reminded of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, Smith’s partner and artistic comrade. His images of queer subcultures, in the gay BDSM underground, composed yet charged, coolly formal, brim with latent violence and sexual power. Like Smith’s performance, his lens-based work explores the edge where desire meets submission, where control and vulnerability are locked in a ritualistic exchange.

Too often, the erotic is conflated with the merely ‘sexy’ – with looking good, with visual allure. While the centrality of aesthetics and the role of attraction should not be denied, eroticism speaks to something deeper: a mode of being. It is a way of carrying oneself, of insisting on the absoluteness of one’s existence, and on the right to pleasure and joy. As the Black feminist poet Audre Lorde puts it, “The erotic is a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” It is, she argues, a source of deeply rooted power that connects the spiritual and the political, the emotional and the embodied.

Such an understanding is essential for figures like Patti Smith. In her memoir Just Kids, she writes that in 1967, at nineteen, she fell pregnant. The child was put up for adoption – a rupture that was both traumatic and formative, catalysing the drive that would shape her artistic life, propelling her to New York, where she met Mapplethorpe. In their first intimate moments, he had tenderly revealed the scars that ran across her stomach and hips. She had been so thin that the skin hadn’t simply stretched as the baby grew; it had split open.

‘Free Money’ captures this toll of poverty – not just as material deprivation, but as psychic limitation. Beginning with a nightly prayer to win the lottery, the track spirals into a frantic dream of buying “all the things I never had.” Working class people are rarely told they can make art. Before Roe v. Wade, before widely available contraception, this was especially true for poor, unmarried mothers.

I remember my own mother – who had worked in British psychiatric hospitals during the 1980s – describing how she encountered older women imprisoned there, institutionalised in their youth for so-called “promiscuity.” Within living memory, such “cases” were met with shame, secrecy, and what might be called a kind of forced disappearance. Social and institutional powers effectively erased these women: committed for decades, they vanished from families, neighbourhoods, and the public record. This shameful history has its roots in the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913, which was frequently used as a catch-all to deal with a wide range of people. In the case of women and girls, this often meant incarceration for “failure to obey current sexual codes,” including having children out of wedlock. This prejudice echoes Smith’s own account of abysmal treatment at the hands of neighbours, doctors, and nurses.

Patti Smith’s success – her mere survival – is a radical act of self-insistence. To make beauty from pain, to fashion her own mythology, to stand in full possession of her own desire and creativity: this is the erotic as Lorde defines it. Not simply sexual, but fiercely life-affirming. A power that insists on being felt.