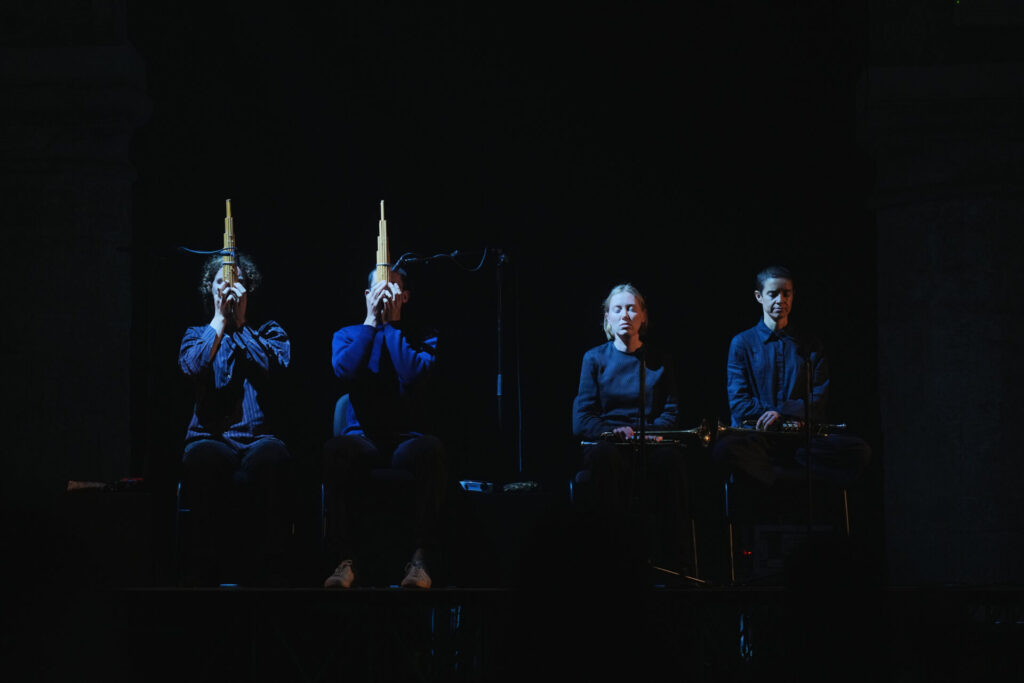

Already, when I entered the theatre, some ten minutes or so before the start of the concert, there was this hum in the room. The deep, angry buzz of idling machinery. With its crumbling stone walls and wood-beamed ceiling intersected by grey arched colums, the Teatro alle Tese would make a fine set for a medieval banquet in some sword-and-socery movie. Tonight it was minimally dressed in a big red rug for the audience to sit or sprawl upon, a few lights. Two members of the late Catherine Christer Hennix’s Kamigaku Ensemble, Amedeo Maria Schwaller and Mattias Hållsten, were sat on stage, slowly turning their Japanese shō mouth organs like spindles, gently heating them over portable braziers to steam off any condensation that would prevent the instruments from sounding. It was such a delicate, dilligent activity to watch against the background of the great loud thrum from the speakers. This was just the background sound, the silence before it started. I could only imagine the sheer volume of what was to come.

When Kamigaku’s pair of trumpet players, Susana Santos Silva and Ellen Arkbro, finally joined the other half of the group, and the music began, at first I thought perhaps I had led myself astray. It was just the two shō to begin with. A thin, silvery sound. If I hadn’t seem them playing in front of me I might have mistaken it for a synthesizer. A long delay effect doubled their efforts, thickening the sound. Then the trumpets enter on long, clear notes. And as the whole thing swells, suddenly this roar emerges from within: a huge, bassy beast of a noise created by no more than a little guitar amp distortion used to bring out the deep, resonant difference tones that are a psychoacoustic byproduct of the notes emitted by the live instruments. The trumpets then emerge as the metallic point of a sound like an arrow soaring through the air – or like the aerodynamically designed locomotive of a runaway train hurtling through a tunnel towards you. It sounds, in fact, quite a lot like the Northern Line. It howls. But it does not clatter like the Tube. It does not feel sweaty and earthy and enclosed, weighed down by several sedimented geohistorical strata. On the contrary: it shines, reaches out, bursts open. It feels weightless, coruscating, fleet-footed. That is, by any ordinary definition, it is the very opposite of heavy. It is a music of light and lightness.

Recently, I have been having doubts about the usefulness of the word ‘heavy’ as a descriptor for a band or a track or whatever – ever since Stephen O’Malley told me off for using the phrase ‘heavy metal’ in a text about a project he was involved in. A great deal of the music I like most, of the music that I find most enlivening and exciting, is loud and noisy and pretty abrasive-sounding. It is music that hits hard and doesn’t fuck around. But I balk at calling it heavy. It feels like a very Boomer word somehow, still stuck in the 60s and 70s. I find myself picturing Neil the hippie from The Young Ones. It is really heavy, man.. To be ‘heavy’ suggests a kind of torpor, a ponderousness, a sort of trudge. Heavy food is stodgy, it is hard to digest and will probably make you feel bloated and enervated. Heavy work is onerous and unpleasant. A heavy heart is gloomy and reluctant. None of these things sound like a good time.

This is my second consecutive trip to the Venice Biennale Musica, an event which, somewhat confusingly, takes place annually. It is also the festival’s first year under the aegis of new artistic director, Caterina Barbieri. Already, everything feels different. The audience skews noticeably younger, for one. The programme also features fewer performers playing the music of other composers; more composer-performers playing their own music. While last year, I found myself criss-crossing town to attend concerts in a variety of theatres in different areas, now almost everything is happening within the Arsenale itself, so in some ways it feels a bit more integrated into the main Biennale (which is focused on architecture this year and also takes place largely in the one-time engine of the early modern Venetian Republic’s military might). But for some reason there are now no chairs for the audience, so everyone has to sit on the floor, which is obviously very bad (not least for my back). And the Arsenale just generally has kind of a weird vibe after hours. As a result, it feels a bit like we’re squatting. As if a bunch of weird music people with beards and zip-up North Face jackets had broken into the art fair at night to put on a bunch of extremely gnarly-sounding concerts.

The day after Kamigaku Ensemble’s set, I’m back in the Arsenale, in the Serenissima Republic’s old arms depot, for a new work by British composer Jasmine Morris. There’s a string quartet spread out on risers about the room: a violin each to my left and right, cello and viola in front of me with several metres in-between them. The music starts with a series of almost inaudible sounds – the rubbing of a bow against the wooden body of a violin or striking the muted and dampened strings of a cello. It’s all close-miked and electronically processed into a series of menacing rumbles and flickers by Morris herself, on the computer just behind me. As the thing builds, you start to hear taut, jerky string gestures poking out of the murk: snap pizzicato and glissandi played on the bridge. We get to hear all the little extended tricks that string players like to pull out of their sack of techniques. The electronics are rich and deftly, subtly applied with occasional bursts of indistinct field recordings for texture. But in contrast to the Hennix the night before, it really does start to sound pretty heavy. It is not especially loud or noisy. There are no blast beats. But it is thick and weighty, like it would slow you down if you carried it on your back. To be honest, it soon gets to be a bit of a drag.

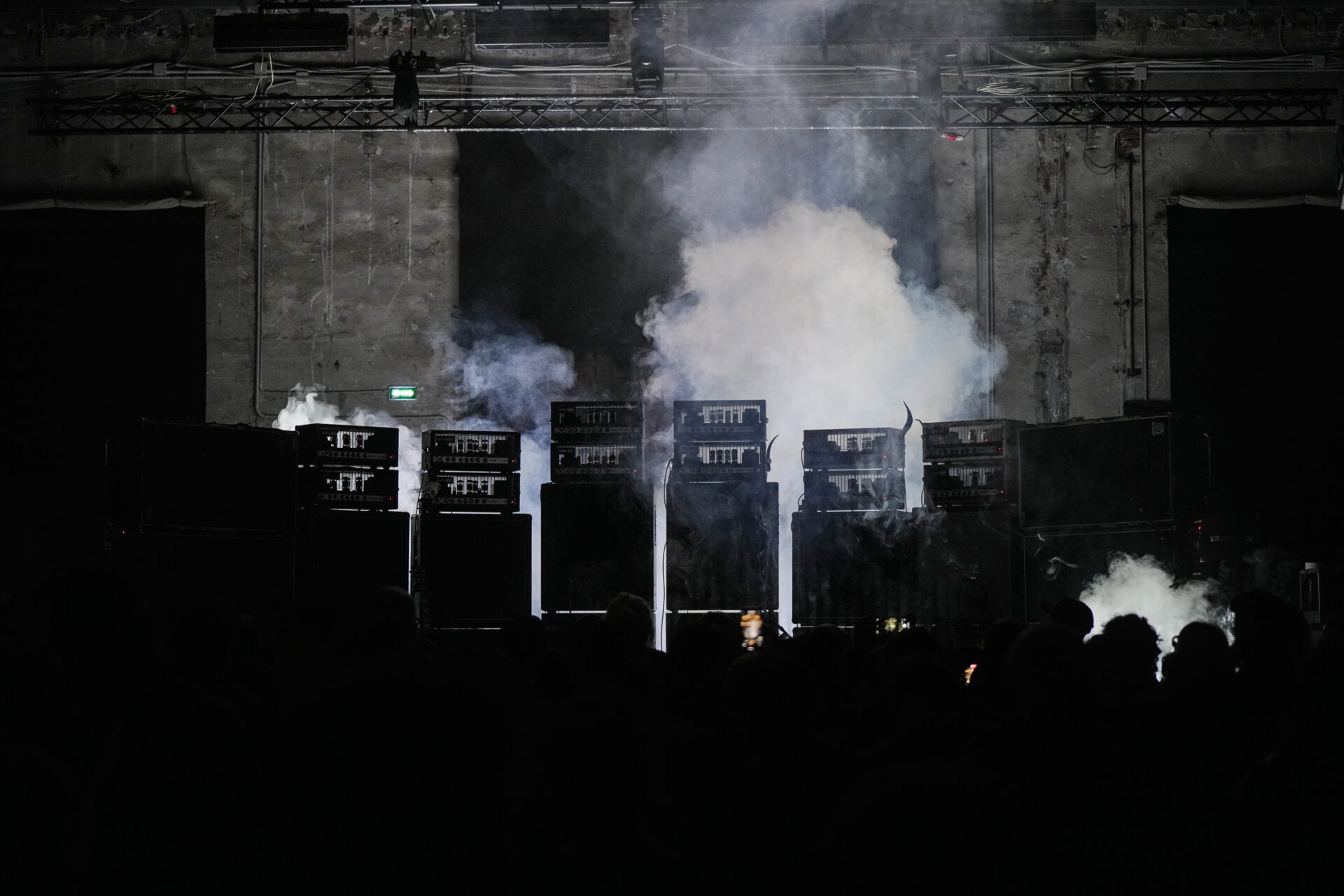

By the time Sunn O))) come on stage in the Teatro alle Tese later that night there was so much dry ice in the room I thought it might rain. As ever, in their Benedictine cosplay with devil-horn fingers aloft, you cannot fault their commitment to the bit. And then that familiar needles in the ear drum sensation as the first chord strikes. There are at least ten amplifiers on stage. I’m standing about as far away from them as I can without actually leaving the building and I can still feel the air around me quaking. Looking out across the crowd, I’m confronted with a sea of phone screens, all filming the stage for posterity. There isn’t much to see through all the smoke, but much as at the similiarly camera-hungry concerts of Taylor Swift, the mobile recording says, I was there.

Sunn O))) shows share with Tay-Tay’s Eras Tour the promise of something more than a gig. They promise an experience – and perhaps a certain feeling of communion. With their monastic garb, it’s easy to imagine that O’Malley and Greg Anderson’s slightly theatrical tendency to slowly raise their pick hands before bringing them down upon the strings of their guitars as a gesture of benediction. And in the individual audience members who raise clawed hands to the sky in response, one can picture the ecstatic penitent at a revival meeting, filled with a yearning for transcendence, for ascension. As it comes to an end with a triumphant roar like the whole earth screaming, I noticed several muscles in my belly unclenching and a lurch in my throat. But I also felt like I was coming back down to terra firma, as if all that trembling in the air had somehow borne me aloft, lifted me up into the sky. As if within all that density of sound there had been this buoyancy, a certain giddiness. A lightness.