Rhythm is both the song’s manacle and its demonic charge. It is the original breath. It is the whisper of unremitting demand. ‘What do you still want of me?’ said the singer. ‘What do you think you can still draw from my lips?’ Exact presence that no fantasy can represent. Purveyor of the oldest secret. Alive with the blood that boils again and is pulsing where the rhythm is torn apart. How your singer’s blood is incensed by the depth of sound. Lacerations echo in the mouth’s open erotic sky where dance together the lost frenzies of rhythm and an imploring immobility.

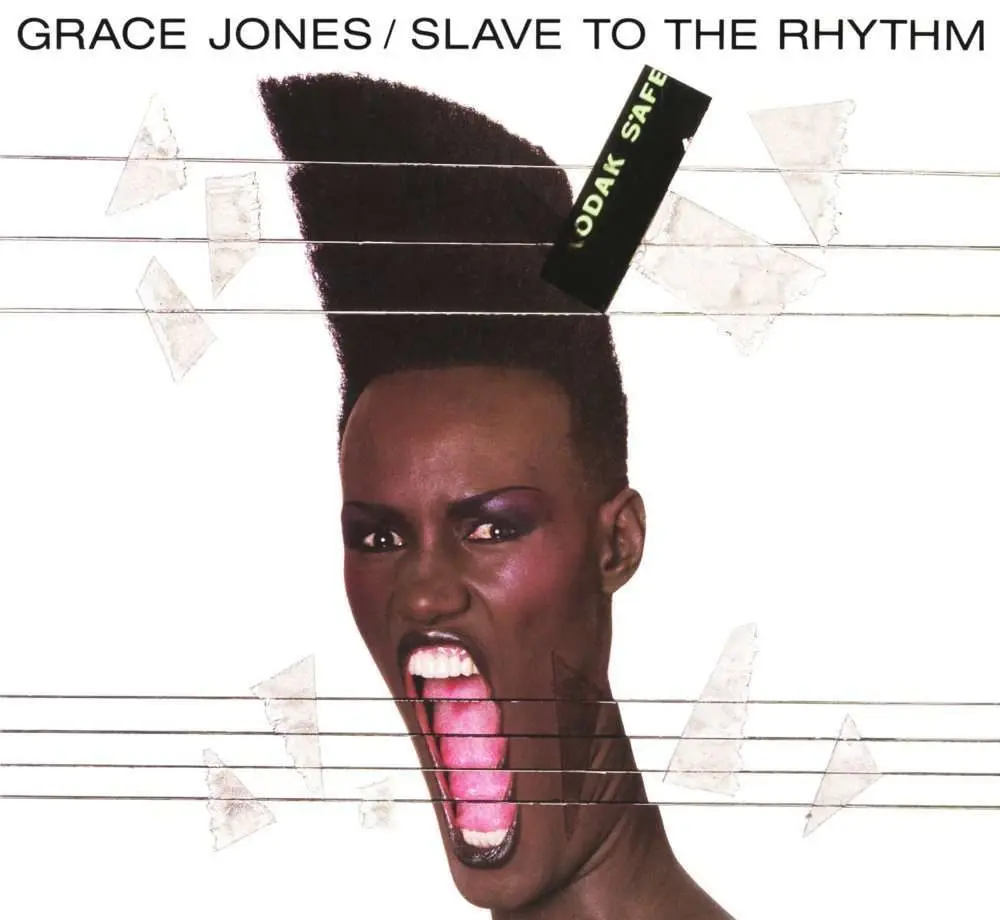

It’s been forty years since this passage was intoned at the start of ‘Jones The Rhythm’, the opener to Grace Jones‘ Slave To The Rhythm, and it’s still no clearer how you are supposed to react to it. Not helping matters, it isn’t clear who actually wrote it. Reading recent retrospectives, it is widely attributed to Jean-Paul Goude, photographer and Jones’ former lover who is liberally quoted on the album. But this particular paragraph doesn’t appear in Goude’s book Jungle Fever, the source of other quotes. And this was a release on the ZTT label, then in its pomp following the success of Frankie Goes To Hollywood. Just as Paul Morley, journalist and ZTT co-founder/PR/jester/theorist mischievously invented quotes for Frankie on Welcome To The Pleasuredome, maybe he did the same here. ‘Jones The Rhythm’ is certainly so spectacularly pompous that it’s either taking the piss or is written by a heroically pretentious figure; maybe it is both.

What we do know is that the words were recorded by Ian McShane, an old friend of producer and ZTT co-founder Trevor Horn, after a chance encounter in a fish and chip shop. While McShane’s gorgeous voice lends gravitas to the passage, for those of us of a certain age he will always be Lovejoy and hence a far more prosaic figure than Grace Jones, Jean-Paul Goude or even Paul Morley.

Slave To The Rhythm is an album which ensures the listener can’t ever be sure how they are supposed to react to it. Is it deeply serious high art or a parody of it? Are we being teased and, if so, why and by whom? Were the team behind the album – Trevor Horn, Stephen Lipson, Bruce Woolley and Simon Darlow – teasing each other? And is this Grace Jones’ album anyway or some kind of high-concept ZZT project? Is this her vision or did Trevor Horn turn her into Paul Rutherford in a designer frock, or worse, one of Frankie’s ‘the lads’ – a bit part player in her own story?

The answer initially seems no clearer now than it was on the day I bought the album, a callow 14 year old who loved Frankie Goes To Hollywood and found Grace Jones scarily compelling. I’d seen her perform the song on Wogan and found it baffling and thrilling, which it still is. Her high fashion garb included a striped hood that hid her face completely. Yet her body mimed the song with utter conviction and, towards the end, with the announcement, “And now ladies and gentlemen, here’s Grace!” she pulled off the mask to reveal her always-magnetic visage.

This didn’t seem to be a satire of miming of the sort that, by 1985, was a venerable TV tradition. What was it then? More likely it was a statement of utter conviction in its absurdity. In her later years, she has performed the song while rotating a hula hoop (including, gloriously, at The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee at Buckingham Palace in 2012), with the same conviction. Her modelling career had already compelled her to pose in any number of relatively ridiculous outfits and situations. Throughout it all, she has, visually-speaking, remained fierce and magnetic, daring you to find her ridiculous.

There’s another side of Grace Jones though. If you’ve ever seen her interviewed or read her book I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, a different artist emerges, one who is fun and full of laughter. The introduction to ‘Jones The Rhythm’ may be portentous and the song itself is stunningly dramatic, but the way it ends is instructive. The music peters out and Jones exclaims, “Oh, that’s weird!” before collapsing into a fit of giggles. Then Paul Morley welcomes her (to the interview of which we hear extracts throughout the album) and she explains that it was her voice that has gotten weird as she “just choked on my saliva”. It’s a magnificently bathetic ending to the beginning of the album.

Slave To The Rhythm almost dares itself to collapse under the weight of its own self-indulgence. As with Welcome To The Pleasuredome, Trevor Horn and team display an intoxicating joy in exploring the emerging possibilities of the studio in a period of rapid technological advancement. The album grew out of a decent enough song that originally featured Holly Johnson on vocals as a suggested follow up to ‘Relax’. But after it was handed to Grace Jones instead, and with a seemingly elastic budget and timescale, the song grew outwards into a series of remixes that are so different from each other that it’s sometimes hard to see how they overlap. In fact, it would be better to describe the album as a set of variations on a theme; common in classical music but rare in pop. The end result is an album which is part-mess, part-statement.

It is a decadent album, entirely appropriate to the intersection between art and fashion that Grace Jones has always inhabited. As such, it would be very easy to choose to hate it. And Trevor Horn gives the doubter plenty of opportunities to do so. ‘Operattack’ is the nadir, a ham-fisted orgy of cacophonous samples that even Trevor Horn disowned in his own memoir. What there isn’t, though, is filler, such as the inclusion of ‘San Jose (The Way)’ on Frankie’s Pleasuredome. For better or worse, everyone involved in the production of Slave comes across as absolutely invested in whatever it was that they thought they were doing.

When it worked, the obsessive attention and lavish expense that ZTT encouraged and underwrote, produced a recording that still, 40 years later, is capable of flooring you. Often, it’s the irresistible groove that draws you in. Horn and co worked with Go-Go percussionists in early sessions for the album, and some of the tracks (including the single, here entitled ‘Ladies And Gentlemen: Miss Grace Jones’) reproduce the punchy drive of what was briefly the most exciting dance genre around.

For my money, the most extraordinary track on the album – as well as the most problematic – is one that seems to owe little to the original version. I’m not sure that Trevor Horn has ever surpassed the slinky and erotic loop that provides the spine of ‘The Frog And The Princess’. It reminds me a little of Peter Gabriel’s work with Daniel Lanois at the time, both of whom were fascinated with the possibilities of embedding dance beats within dense layers of sound.

What Peter Gabriel would likely not have done, though, is devote an entire song to readings from Jean-Paul Goude’s reminiscences of his relationship with Grace Jones. You could choose to hear it as a meditation on the line between artistic and erotic obsession. Alternatively, you would be justified in hearing it as the insufferable monologue of some bloke who managed to get away, for a time, with disguising his dodgy fascination with Black female bodies as artistic exploration. (And there’s a lot more of this stuff spread across his excruciating book, Jungle Fever.) That fetishistic fascination, as the people who made it were likely well-aware, becomes even more problematic on an album by a Black artist that repeatedly riffs on her declaiming the word ‘slave’.

Dodgy or not, ‘The Frog And The Princess’ remains hypnotic; come back again for yet another chance to fret at the racial politics, stay for the groove, or vice versa. Part of the genius of the way that Horn builds the track, is that Goude’s narrative on ‘The Frog And The Princess’ eventually peters out and – as with the opening track – only Grace Jones remains.

I think we are being told something here, should we choose to hear it. It’s easy to assume that Grace Jones’ own role in the production was to be the muse, the inspiration for Horn and co. but little more. Though if you read her memoir, she is not only effusive in her praise for Horn, she praises him as he “never said no to any of my ideas” and that “he allowed me to experiment with my voice in a way no one had before.” She also speaks warmly of Goude and actually seems to have been an equal partner in that relationship.

The memoir proves to be the key to unlocking Slave To The Rhythm. It works as an ironic commentary on the way that Grace’s body is eroticised and her agency is denied. The album is an expression of her. That ‘her’ isn’t just a symbol for something else. Indeed, the short interview extracts with Paul Morley that are scattered across the album, seem to have been purposely chosen to humanise her. If much of her visual representation by the likes of Goude seems to suggest an impenetrable, statuesque hardness, that isn’t the only Grace Jones we hear from on Slave To The Rhythm.

For all of Trevor Horn’s obsessive tinkering, the production team never forgets Grace Jones (in the way they sometimes did with Frankie Goes To Hollywood). Vocally, she achieves an engaging combination of icy control and rich warmth. It’s as though her rich voice subverts and comments on her mechanistic, statuesque look.

Of course, maybe I am also guilty of imposing my own narrative on Grace Jones by attempting to impose some kind of order on an album that often seems like it doesn’t make much sense. What we can say for sure is that no one is ever likely to make an album like this ever again. The studio no longer excites to this degree and record labels are unlikely to sign off on unlimited budgets for open-ended projects. Ironically, ‘enslavement’ by the 80s record industry may have been preferable to the apathy of over-production and the limitless technological possibility that can be accessed in the most modest of bedsits.