As history is written by the victors, so is our understanding of genre flux. That’s doubly true when it comes to subcultures where the curious outsider has to rely on gatekeeping narrators to tell them what it’s all about. Club culture in particular has always suffered from this: there have always been vested interests that have pruned and groomed their narratives to suit their own aesthetic, ideological and social leanings. This dynamic is familiar to many, for example, in the way the UK Balearic Mafia created an information bottleneck around 1988 And All That, an origin myth around a small group of friends who just happened to end up in positions of music industry power, which set the tone for the way dance music was talked about right through the 90s. You can see similar narratives formed by the way the mainstream and just-left-of-centre indie music press were only really able to grasp dance culture once it had recognisable faces, videos and big albums-of-the-year, and thus equate dance culture with Chems-Aphex-Daft-Punk. Likewise a quasi-academic network of tastemakers formed as the inky press tipped into the blogging age drew their own hard lines around which sounds and scenes were and worth considered worthy of kudos in those sections of Cultural Studies where only four or five authorities are ever cited, which in turn ossified into another set of received opionons in Online Discourse.

All of which is fine. No (or not much) shade on any of those involved. This is simply how things function, and it’s interesting to see that there have been a lot of correctives to all this more recently, not least in the flood of dance culture books of the past five years or so. It’s notable, for example, that the importance of the traveller convoys and free party scene has been more recognised lately, and genres like gabber, trance and hardcore techno are now getting treated with seriousness they weren’t afforded before. However, some historical strands still remain extremely under-examined, which in turn skews any big picture perceptions of what club/dance music even is. One such is what you might broadly call the psychdelic-industrial complex. Sure, plenty of dance acts, especially those who fall into tQ’s orbit, will cite Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire or Front 242 or generalised “post punk” or “shoe gaze” as influences, but the lines of connection that weave through the 1980s, through those acts, into the acid house explosion and out through into the fabric of all that followed are incredibly complicated, and there is a lot to unpick about all that transpired through that period.

The work of Edinburgh band Fini Tribe (or, later, Finitribe) is perfectly illustrative of this. They are best known for the industiral electro with mangled church bell samples and aggro chanting of their 1986 ‘DeTestimony’ – which was notably picked up by Amnesia resident DJ Alfredo, and became a key part of the mix that became known as Balearic. Indeed it featured on the following year’s era-defining Balearic Beats compilation put together by Trevor Fung (along with obscure DJs “Razor” Tong and “Oakey”) and has been remixed, re-edited and interpolated continuously ever since. They managed to segue pretty much seamlessly into the rave new world that followed: side by side with fellow psychedelic-industrial Scots The Shamen, they embraced the DJs that embraced them and were soon working with 808 State, Andrew Weatherall, Justin Robertson and co, and while they didn’t (and probably didn’t want to) match The Shamen’s delirious mainstreaming, they went on to roll out banging, trippy, Eat Static-like trance at leftfield raves through the 90s.

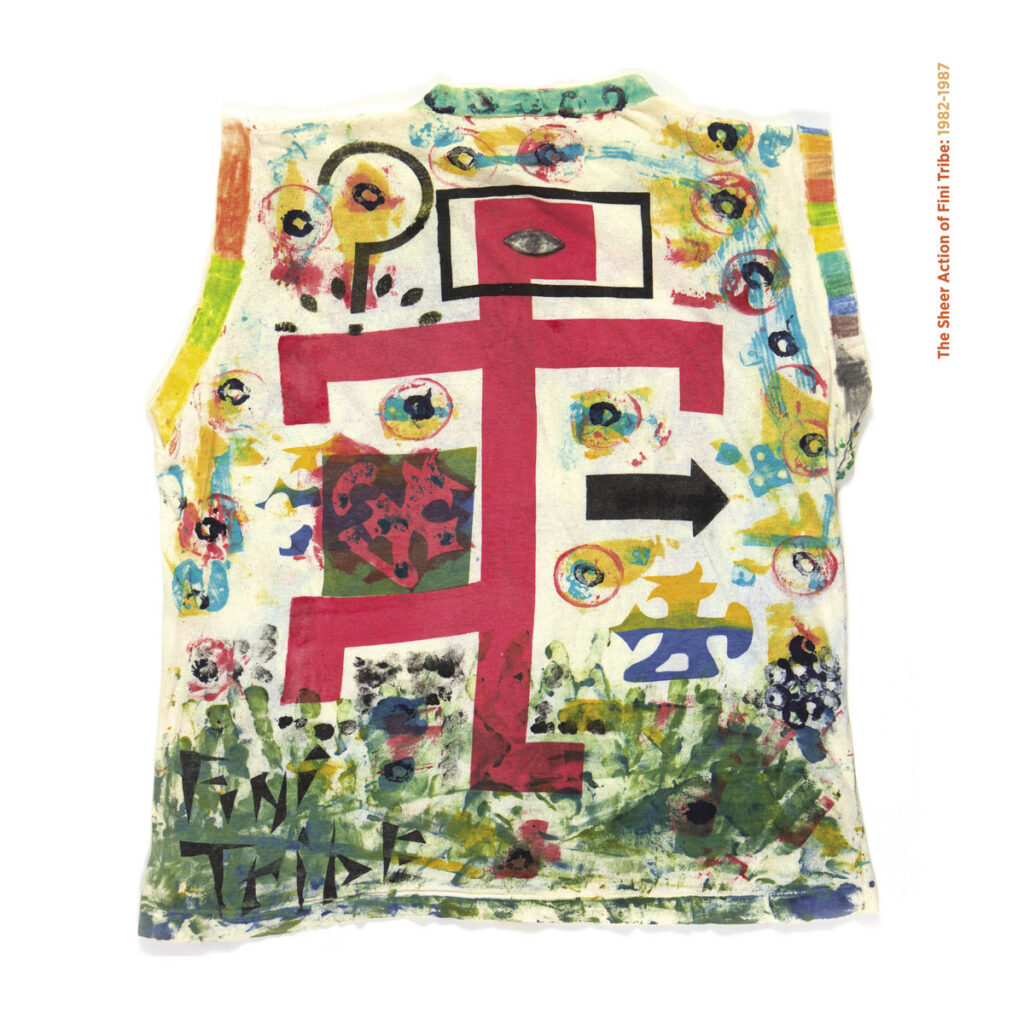

Before ‘DeTestimony’ though, they were part of a heady and heterogenous brew of 80s alternative culture, which is kind of captured on this compilation of early demos, singles, a Peel Session and live tracks. It’s often raw, sometimes scrappy, and the sheer range can be baffling, but give it time and some fascinating patterns and contours start to emerge. ‘DeTestimony’ is here as is ‘I Want More’ the crunching and crashing Can cover they recorded for Chicago’s Wax Trax!, aligning themselves for a while with Ministry and Revolting Cocks (indeed founder Chris Connelly would leave to join both those bands in 1988). There’s plenty else that sits neatly alongside them: a live studio take of ‘Do We Understand Each Other’, for example, is a sterling example of the kind of crashing industrial funk that Tackhead and Adrian Sherwood were perfecting at the time, with sampled orchestral stabs that are startlingly prescient of hardcore rave that was to come. ‘Idiot Strength’ is a classic Wax Trax! slammer, with vicious synthetic snares but a groove not a million miles from Faith No More.

That’s all great, and if you enjoy early Meat Beat Manifesto, Skinny Puppy or Nitzer Ebb you’ll be in hog heaven with all that stuff. But it’s the earlier, pre-drum-machine material where it gets weird and murky and the complexity of the influences really becomes apparent. Songs like ‘Splash Care’ and ‘We’re Interested’ live in an interzone where goth, crusty-festy rock, jangle pop and even the high drama of the exact point where Simple Minds crossed over from artsy new wave to stadium drama all coexist and flow into each other. There are bits that sound like Joy Division at their most light-footed but with the elegant, classically-informed guitar chime of Durutti Column or Felt. There’s a huge sense of hallucinogenic and Dada weirdness, too. Fini Tribe were fond of lightshow barrages and peculiar geometric costumes, and in classic post punk autodidact fashion loved to delve into the esoteric and absurdist: the name comes from “Finny Tribe”, a name given to certain fish by the mystical order of the Rosicrucians. This psychedelic edge comes over in the proclamatory and incantatory vocals which tap into a similar vein as Julian Cope or Hawkwind at their most space ritualist. There’s more than a bit, too, of the synapse-short-circuiting jaggedness of Faust and Captain Beefheart on tracks like ‘Curling Theme’, ‘An Evening With Clavichords’ and ‘Cure For Madness’ – and most grippingly of all on the Vocal Mix of ‘Goose Duplicates’. All of this comes together with eerie synth pop chords and spanky bass that foreshadows the electronic era to deeply, deeply peculiar effect.

Not all of this is instantly apparent. The recording on some of these tracks is rudimentary and sometimes it takes a couple of listens to get past the eighties-ness and the indie-ness of it all, but the more you sit with it the more the wonderful wrongness of it all gets under your skin, and the more the variety and sense of possibility emerges. This was the eighties of proper oddballs like Stump and The Cardiacs, but also of PiL, Siouxie and Budgie’s The Creatures, Sisters of Mercy offshoot The Sisterhood finding weird ways to make the rigid rhythms of the time groove, of Sheffield punk-funkers Chakk taking major label money and throwing it into FON studios where some of the greatest house and techno would emerge. It was the eighties where The Shamen and Loop were frying their minds, where the goths of The Batcave were as important to British people discovering drum machines as were the trendier denizens of the Blitz Club, where Mark Stewart and Tackhead were dubbing the sound of the psychedelic apocalypse. This wasn’t just “post punk” in the commonly used sense which usually homes in on 1979-81, it was a whole decade’s underground of experimentalism that not only equipped acts like Fini Tribe, The Shamen and Meat Beat Manifesto and DJs like Colin Faver, Dave Clarke, Luke Slater and JD Twitch with the tools to join in when house and techno arrived, but to actually shape it and the future of dance music as they were going. This collection can be a tricky listen to say the least, but as a portal into weird and hidden histories, it is very much worth your time.