While often claimed as anomalous, an expression of an ‘old Weird America’, 1985’s grittily romantic Rain Dogs has rather more relevance to the sleekly pragmatic 80s than is immediately apparent. Rain Dogs celebrates the lives of the marginal and dispossessed of Reagan’s America, coalescing on New York, like transplanted Angeleno Tom Waits, just as the outsider capital was becoming the yuppie capital. Yet the oddity of the 80s was how such marginal culture thrived in this inhospitable environment, the way the underground, the oppositional and the eccentric acquired mainstream cult status. Indeed, Rain Dogs would be Waits’ first charting album. So, while Waits’ attachment to organic instruments set him against 80s sonic convention – Rain Dogs is the sound of breath wheezing, fingers twanging and hands thumping – it positioned him in a community of 80s outsiders like The Pogues, Elvis Costello or Siouxsie & the Banshees. Consequently, Rain Dogs endures as a reminder of an old weird 80s that would soon be sanitised, just like the city the album salutes.

Going from bougie to gnarly in a block, New York was always a city of contrasts, but by the 80s, was a city in flux. Its downtown lofts had long provided asylum for bohemians, artists and eccentrics, its streets refuge for the down-and-out and its nightspots boltholes for deviants and drunks. Following the city’s fiscal crisis of 1975, the terms of a business consortium’s bailout were spending cuts, gentrification and financialisation – cornerstones of nascent Reaganism. Soon yuppies were buying up the lofts and hoovering up the bohemianism, as can be read in Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights Big City (1984), seen in Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), After Hours (1985), Something Wild (1986) and Wall Street (1987) and heard in the music of Talking Heads. You can hear it more laterally in Waits, as the new arrival soaked up the city, capturing its sounds on a cassette recorder and its character in songs.

While a fair few millionaires pop up on Rain Dogs, they’re tied to trees or shovelling coal and Waits’ sympathies are plainly with the discarded and dispossessed amid the era’s gold rush. Like that other music emerging from New York’s streets, hip hop, Rain Dogs champions the period’s losers rather than its winners, its beyond-cool outsiders over newly cool organisation men, its historic grit over contemporary glamour. Waits’ New York is a city of drunks, criminals, the homeless, the unemployed and the insane (the phrase “mad as a hatter” crops up regularly). And it’s a city of immigrants: Cubans, Chinese, Italians, Irish and “Puerto-Rican Chinese” commingle throughout the album. Here and historically New York isn’t just the arrival point in America (or escape from it) but a metonym for it, a city of the free in an idealistic sense far beyond the atavistic American Dream reasserted by Reagan.

What Waits is doing here is creating a mythology, a romanticism which acquires realism through his adroit capture of visual and aural detail. The spoken-word ‘9th & Hennepin’ – splicing New York and Minneapolis – is a late-night diner tableau, Edward Hopper put to words and music, its wails, thrums and whines summoning police-sirens, passing trains and the sound of distant sobbing. Just as dialogue brings a novel alive, so does Rain Dogs’ street demotic, whether it’s documentary – ‘Walking Spanish’ is a Death Row inmate’s last journey – or fictional, like the same song’s imaginary bluesman Blind Jack Dawes … or indeed a ‘Rain Dog’. As befits a title track, ‘Rain Dogs’ is a three-minute manifesto, the album’s map from subject matter to musical palette. Over busker accordion and barrio marimba, the song hymns those for whom home holds no allure, lost dogs who live their lives in the city’s streets, parks and bars. Rather than being a manifesto of immiseration, society’s rejects themselves reject society, proclaiming a community beyond constriction or convention. “How we danced and we swallowed the night/ For it was all ripe for dreaming” the rain dogs rhapsodise, as Marc Ribot’s Beefheartian guitar capers and cavorts with complementary abandon.

Another New York rain dog, film-maker Jim Jarmusch became a regular Waits collaborator and featured both Waits and ‘Jockey Full of Bourbon’ in 1986’s Down by Law. Another scion of the city’s outsider scene, Ribot adds surf-Beefheart guitar to the track’s Latin lurch and shaky shuffle. The declamation of a drunk unrepentant about deserting his family, such proclamation of backstreet liberation talks back to Wall Street’s purely financial freedom. That contemporary push for profit is addressed directly in ‘Diamonds & Gold’, leaving its pursuers “wounded but they just keep on climbing”, though like growing numbers in the 80s, “they sleep by the side of the road”. The closing hobo’s lullaby ‘Anywhere I Lay My Head’ (“I’m gonna call my home”) compellingly contrasts to Paul Young’s slick 1983 Marvin Gaye cover ‘Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home)’. Where in Gaye’s atavistic ethos, cheating is freedom, in Waits’ philosophy freedom is making the best of life cheating you: “my pockets were filled up with gold” but now, homeless and penniless, “the wind is blowing cold”. Sucked in and spat out by the system, the bum asserts the album’s bleakly romantic version of freedom, cast out but carefree, as a New Orleans brass section gives him a suitably rousing sendoff.

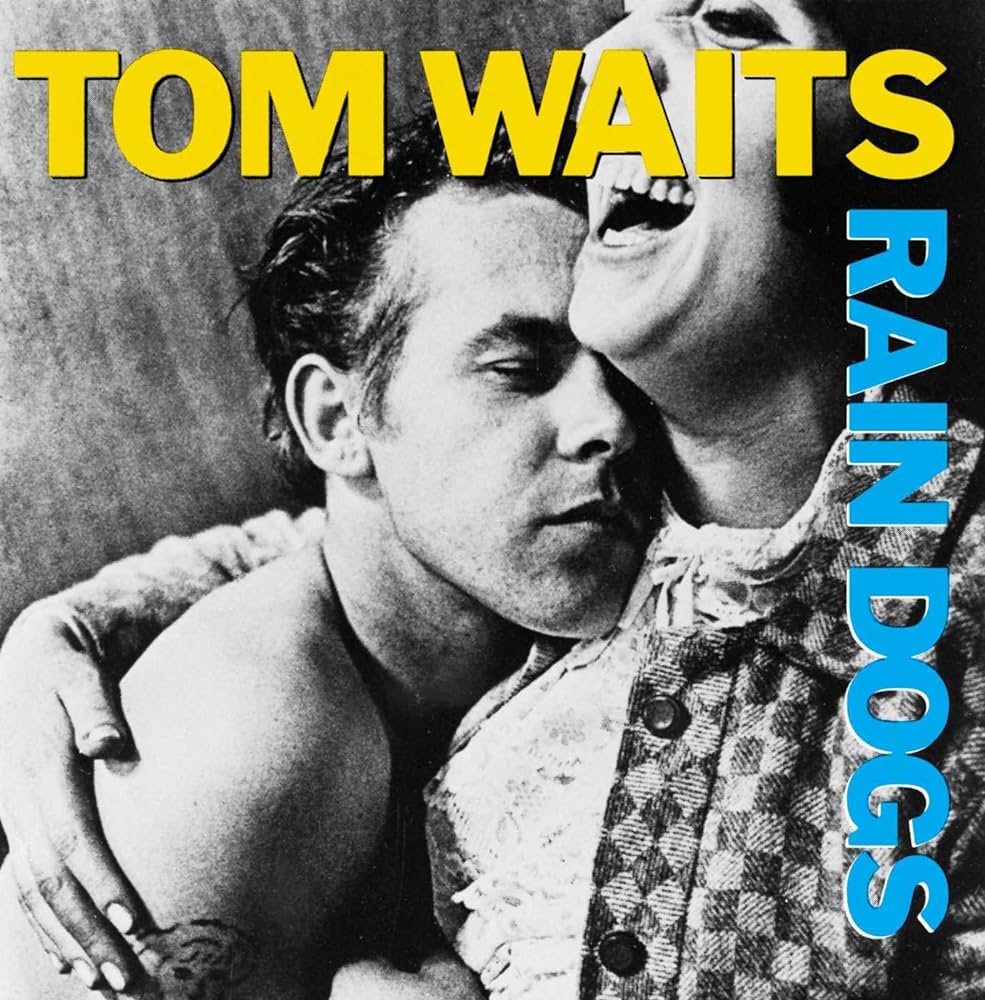

Beyond New Orleans, New York is the most European of American cities and Rain Dogs has an intermittent Euro feel that, allied to its atmospherically seamy street-tales, gives Waits a curious commonality with another 80s outsider, Scott Walker. Port cities like New York link America to Europe – the cover is a Anders Petersen shot of a couple taken in Hamburg’s Reeperbahn red-light district – while connecting both continents to the Far East that’s regularly referenced here, as it was in Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s Weimar cabaret songs. Weill-suffused opener ‘Singapore’ is a cutup sailor’s chart, staggering from ship to stern, docks to Parisian sewers, Hong Kong watering holes to ports in sexual storms (the brilliantly surreal “making feet for children’s shoes”). Over a careening oompah rhythm, Ribot appears to be playing random notes, whilst Waits debuts the Mitteleuropean sprechgesang he’d re-use regularly in the coming years. He’s clearly having a ball, and the track manages to be simultaneously funny, sinister and beautiful – as on the brass that slithers in at 1:37.

This Weimar schtick, influence of new wife Kathleen Brennan and first aired on 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, links to Waits’ longstanding Broadway tendencies, through theatricality and a common root in jazz. The terrific ‘Tango Till They’re Sore’ splits the difference between decadent cabaret and dirty jazz, Europe and America, its drunken piano and strip-club trombone providing rousing accompaniment to a carouser’s joyful instructions for his funeral. “Let me fall out of the window with confetti in my hair /Deal out Jacks or Better on a blanket by the stairs… Send me off to bed for ever more”. Weimar’s haphazard loucheness isn’t far removed from Waits’ lizard loungeness on tracks like ‘The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me)(An Evening With Pete King)’ (1976) to which ‘Tango’’s artfully chaotic piano-style is a European cousin. Stylistically, ‘Cemetery Polka’s budget horror-movie organ has no business attending a cabaret knees-up but thematically it fits perfectly with the circling relatives bemoaning dying “tightwads” denying them their deathly dues. The missing beat at the end of each verse gives the track a brilliantly off-kilter feel, a deconstruction of musical convention that recurs throughout Rain Dogs, such irregularity and unconventionality mirroring the songs’ subjects.

It also mirrors hip hop, and Rain Dogs is full of ‘missing’ frequencies and instruments – mostly cymbals, sometimes bass, and for much of the album’s second half, guitar. The bass-free ‘Clap Hands’ draws on Shirley Ellis’ similarly percussive and playful 1965 hit ‘The Clapping Song’, redeploying its meter and nursery rhyme imagery, but Waits’ song is slower, more mysterious, more melancholy. Michael Blair’s percussion clanks and chimes melodically, the track’s rhythm lulls like a swaying train over Waits’ delicate acoustic arpeggios, while even Ribot’s electric eruptions are just another night on the subway. On the A-Train, millionaires sit alongside bums, gangsters in Paladin hats ride alongside bookworms, all human life is here, never condescended to but conveyed with humanist warmth. The guitarless ‘Gun Street Girl’ is a gritty noir narrative, the antihero buying a Michigan 20-gauge on Little Italy’s titular street, leading to a double murder, dyeing his hair at a gas station, hiding out in the woods, starting a new life in a new town, but still winding up “dancing in the Birmingham jail”. This dense narrative is accoutred with a bare-bones blues of twanging banjo, double bass and hammered percussion, with lyric and music perfectly matching its prison worksong chorus (“John John, he’s long gone”). Dispossession and deconstruction defiantly combine here, linking back to hip hop as a response to Reagan’s covert race war.

For all this irregularity, several tracks pursue the rocky tendencies Waits first revealed on 1980’s Heartattack and Vine – Rolling Stone Keith Richards even plays on three cuts. But where on the claustrophobically atmospheric Swordfishtrombones the rockers felt out of place, there’s space for the electric ‘Big Black Mariah’ and ‘Union Square’ inside Rain Dogs’ eclectic sprawl, paralleling that of New York itself. Indeed ‘Union Square’ is another city vista, full of drunks, drag queens, welfare hotel patrons and sex workers.

The album’s most regular ‘rock’ track is the Springsteen-esque ‘Downtown Train’, which, Rod Stewart’s anodyne 1989 cover notwithstanding, is still a thing of wonder. Simultaneously melancholic and ecstatic, the song’s lonesome protagonist yearns for connection but achieves only distance, glimpsing his object of desire in a crowded train of “Brooklyn girls”, and as he paces the street outside her window. But where she and the Brooklyn girls fail “to break out of their little worlds”, he is free, a freedom that’s again both loftily romantic and flatly realist. So rather than being an anomaly on an album of oddities, ‘Downtown Train’ fits perfectly – another poem to New York, another ode to the outsiders looking in. This is beautifully captured in Jean-Baptiste Mondino’s monochrome video, with its sleepless people in poky apartments, cheek by jowl but atomised, while out on the street a sozzled & swaying Waits serenades them in serene solidarity.

‘Downtown Train’ has rather overtaken ‘Time’, the album’s more uniquely Waitsian highlight. Over a simple but yearning melody, backed by his own acoustic, Larry Taylor’s double bass and William Schimmel’s shimmering accordion, Waits’ lyric is a poetic cascade of non-sequiturs. “Well, she said she’d stick around/ Until the bandages came off/ But these mama’s boys just don’t know when to quit/ And Matilda asks the sailors/ “Are those dreams or are those prayers?”/ So close your eyes, son/ And this won’t hurt a bit”. This combination of giddy surrealism and gritty realism makes ‘Time’ both ineffably mysterious and emotionally immediate. The chorus, “It’s time, time, time” is both imperative and meditative: “It’s time that you love”. Whether spent well or wasted, time encompasses both love and loneliness, gain and loss, pleasure and pain, as song’s camera pans across New York and out across America, embracing its outcasts and oddballs, its damaged and its dreamers. Yet for all its carnivalesque quality, Rain Dogs isn’t ever a freak show, but rather an expression of empathy for the unconventional in a coldly conventional age. The album isn’t just an observation of the marginal, but a proclamation of membership of it, with Waits gruffly declaring Spartacist commonality on the title track, “I am a rain dog too”.

Toby Manning’s Mixing Pop And Politics: A Marxist History Of Popular Music is published by Repeater