“The churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor soon invade the consciousness, the charting instinct. Eight churches give us the enclosure, the shape of the fear; – built for early century optimism, erected over a fen of undisclosed horrors, white stones laid upon the mud & dust.”

And so Iain Sinclair, who Alan Moore refers to as “the finest and most necessary living writer in the English language,” begins his seminal work Lud Heat: A Book of the Dead Hamlets. A landmark book self-published fifty years ago through his own Hackney-based press, Albion Village Press.

Lud Heat is a hand-held pyre. A blazing book that consumes London, the public sector, and Nicholas Hawksmoor in a conflagration of prose and verse. It also demarcates a fast fracture in British cultural history, where the buoyant optimism of the swinging 60s collided with the ruinous 1970s economy, which didn’t swing in the discotheques, but from the ceiling.

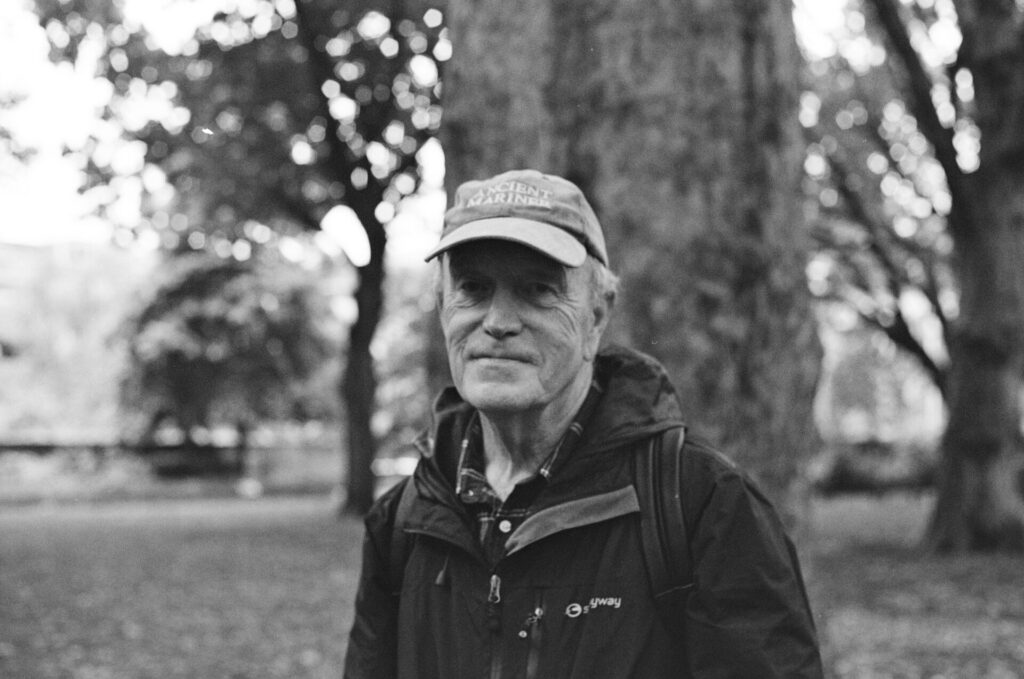

Sinclair, now 82, is wearing a cap that has ‘ANCIENT MARINER’ stitched across it when we meet at Kings Cross St Pancras station. He quickly whisks me out of the busy hall and onto the London streets where you have the profound sense that he is most at ease. We walk briskly from Kings Cross to Swedenborg House, where we conduct the interview, with Sinclair pointing out countless institutions along the way that are unknown to me, including the London Welsh Centre which he remarks “doesn’t even have a copy of Arthur Machen in its library”.

Walking with Sinclair, you feel the importance he holds within a city that feels ready to conspire every inch from its populace. At one point, he takes me down a path that appears closed off to the public to show me a garden in the middle of one of London’s Inns of Court that he believes holds an importance for Machen’s writings. It’s a quiet, serene spot despite being next to a major thoroughfare. However, you sense eyes and cameras watching you, expecting you to leave promptly – but Sinclair never hastens.

At another point, while discussing one of his on-going projects which involves him tracing the footsteps of Vincent Van Gogh, he stops to take a picture on his digital camera of a small bit of graffiti on the pavement. It’s a small innocuous symbol, but strangely it reappears at another location on our walk and then another. Sinclair duly snaps it again. It feels like he is tracking London, trying to capture it as it mutates in plain-sight.

When we reach the austere townhouse of Swedenborg House, which sits only a hundred yards or so from St Georges church, one of the six churches that Hawksmoor worked on that are still in-use, Sinclair describes the period that birthed Lud Heat, the colourful, frenetic, and yet-undiagnosed dystopia of the early 1970s. A period that London historian Roy Porter labelled “a veneer of modernity on an ageing superstructure”.

Sinclair recalls, “everything felt very comfortable at the time, there was no fright about getting employment. No one I knew had any ambition to be this or that, or to have any kind of career, or even to get Jonathan Cape to publish them. It just did not enter your head.” He adds, “there was a whole world of underground activity. There were readings all the time. And I think those first years of the 70s were the best for it, because so much of the 60s had been taken up by psychedelic gangsters and chancers”.

While London’s third eye was twitching in the 1960s, it had been yacked open in the 1970s. The mix of radical art, radical politics, and the radical rich was a powder-keg of strangeness flowing through the streets. Living in the borough of Hackney, a microcosm of the wider city, Sinclair was exposed to it all.

In his book-length interview The Verbals, Sinclair describes a great rewiring of the Hackney area during the early 1970s that allowed him to drift through these nascent worlds as an observer. The infamous experimental art collective ‘Exploding Galaxy Commune’ lived close-by on Balls Pond Road, Stoke Newington was one of the heartlands of the 1970s anarchist group The Angry Brigade, and the radical Antiuniversity of London was a stones-throw away in Shoreditch. Sinclair quickly became exposed to the vanguard of art and anarchy in the city, overhearing conversations about bomb-making in a squat one day and meeting countercultural figures like anti-psychiatrist R.D. Laing the next.

On one occasion, Sinclair recalls returning home to find a wealthy and influential London tailor called Jeff Kwintner looking to recruit him. “He was gathering this weird collection of poets, visionaries, and dowsers around the city and employing them” to help convert “his flagship clothes shop on Regent Street into a John Cowper Powys bookshop called the Village Bookshop”. Powys is a British mystic writer whose approach to understanding place and nature greatly informed Sinclair’s writing. “He had seen Powy’s A Glastonbury Romance on my shelf and he said ‘look! You start work for me tomorrow, fifty pounds a week, come down to King’s Road’.” Sinclair would be sent on missions to Avebury, Glastonbury, and Wales at Kwintner’s request to take pictures and gather information about Powys. “This went on for about a year and then it all kind of collapsed.”

The early 1970s were also a critical juncture for UK poetry, “it was a period when poetry actually got quite organised. There was a sort of trade union of poets.” Alongside the readings and gatherings at bookshops such as Better Books on Charing Cross Road and Compendium bookshop at Camden High Street, there was an array of publications for experimental poets to get their work printed in. This includes the traditionally establishmentarian Poetry Review which had taken on Eric Mottram (called the “best known ‘unknown’ poet in England” at the time of his death in 1995) as its editor, who sought to push British poetry to match the daring of American poetry – giving greater column space for Sinclair and other experimental British poets such as Barry McSweeney, Bill Griffiths, and Allen Fisher. It would form the spine of what Mottram would later call the ‘British Poetry Revival’, a radical re-imagining of what British poetry could be.

Sinclair remembers the huge influence the Beat writers such as William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and revolutionary Black Mountain poets such as Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, and Ed Dorn held over him. In particular Olson’s Projective Verse, an omnivorous technique that absorbed absolutely everything into the ‘field’ of the poem. “I started by being obsessed by Kerouac and Burroughs. Then when at university in Dublin, I was getting in Olson. The Olson Maximus Poems idea of inserting chunks of prose and documentation and whatever else among the poetry was a huge influence”.

In the melee of energies colliding and creating new realms of artistic intrigue, Sinclair would hold an exhibition in 1974 named the ‘Albion Island Vortex’ with artist Renchi Bicknell and the late sculptor and writer Brian Catling. Hosted in a wing of the Whitechapel Gallery, Sinclair recalls, “it was slightly Vorticist in impulse. It took a map of Britain as a mythological centre. Essentially the whole thing was about place. There were stones, bits of wood, all aligned North-South-East-West”. It was a mythic mapping of Britain, but it would be Sinclair’s mapping of London that would be published the following year that would solidify his full vision.

Sinclair had written and self-published several books already, including the psychedelic Kodak Mantra Diaries, a meditation on The Dialectics of Liberation Congress event hosted at the Camden Roundhouse in 1967 that saw Allen Ginsberg, Stokely Carmichael, R.D. Laing and others seek to “demystify human violence in all its forms, and the social systems from which it emanates, and explore new forms of action”.

However, he knew publishing Lud Heat would be a sea-change. “I knew this was really what I wanted to do. Before that, the work I was doing was just something small that you would produce as part of a community. This other thing was much bigger, because it was about a London dreaming.”

The central premise of Lud Heat is a forensic and psychotic examination of geography and time. It’s a motif that Sinclair would become forever synonymous with, better known as ‘psychogeography’. An idea coined by Guy Debord in the 1950s as part of the Paris-based Letterist International.

The book’s initial idea was borne from Sinclair’s odd-jobs he did to keep the money flowing in while he wrote. The day jobs he took from Manpower would coincidently “follow the churches across the city”, including working as a gardener for the local council at St Annes church in Limehouse and St George-in-the-East. Sinclair began to wonder if there was something more to the location of the Hawksmoor churches.

He took inspiration from the deluge of countercultural books in the 1960s concerning earth mysteries, typically trying to decode the neolithic constructs of Silbury Hill, Avebury, and the stones of Cornwall. With a Blakean grandness fuelled by a quasi-Situationist eye, he sought to establish a sacred geometry to link the Hawksmoor churches together.

“It’s now sort of entirely labelled psychedelic, but that was not the impulse at all at the time. I was aware of the method in the 1960s, but it was sort of conceptual and theoretical and I think it didn’t apply much. It was coming out of that Alfred Watkins tradition, you know ley lines or earth mysteries – but basically the idea was that the territory was very rich and it had more of a narrative than you were being given by the official explanations”.

Sinclair drew up the lines of the Hawksmoor churches on a map and other significant places in his life: his home in Hackney, the home of Catling in south London, and a few choice Blakean spots of interest such as Bunhill Fields. Sinclair observed that the drawing-up of the churches created a ‘pentacle-star’ slashed across the capital. The image absorbed him and made him think deeper and darker about the movement of history in London and its external forces: What these lines could mean, what they could make you do, and how many more there may be.

“Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge (the follow-up to Lud Heat released in 1979) are only offshoots of a huge central corpus of mad experimental writing, prose and poetry and just research notes. Pages and pages and pages of this lunacy.” With suitcases full of his manic scribblings, Sinclair eventually “took a cottage down in Dorset in Golden Cap in the winter” to figure it out. He recalls, “it was bitterly cold, I was writing with gloves and balaclava and a coat in a farmhouse. There was no heating and there were rats running about. I started writing the prose pieces for Lud Heat that were not a part of the original set-up. So they all got written in a cluster and I just formulated a book out of some of the elements.”

The frenetic and spontaneous writing matches the fractious, sprawling narrative of Lud Heat which posits the lines linking the Hawksmoor Churches as a “system of energies” that can direct individuals and history. In the book, Sinclair associates the infamous Ratcliffe Highway murders in 1811 with Hawksmoor’s St George-in-the-East and the Jack the Ripper murders with Christ Church in Spitalfields. He states in the book, “each church is an enclosure of force, a trap, a sight-block, a raised place with an unacknowledged influence over events created within the shadow-lines of their towers.”

Sinclair cross-examines the churches’ architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, seeing a deviant genius with a vision for the city who was “obsessed/possessed by pyramids” and who had coded his churches with “twin fears: fire and inundation”. While Hawksmoor has been transformed into something of an underappreciated genius since the publication of Lud Heat, in Hawksmoor’s own letters from the time we find an authoritarian quest mixed in with an aesthetic one.

In his biography of Nicolas Hawksmoor, From The Shadows, Owen Hopkins places the construction of these churches in its proper context, with the “growth of dissenting religious groups in the areas [in the then south and south-east suburbs of London] that lacked adequate church accommodation was a keenly felt concern for the Anglican authorities. This situation provided the immediate and practical justification for commissioning new churches.” These churches were places of worship, but they were also a message, and a form of surveillance on the communities living there. They were, in effect, the first of the capital’s many ‘Grand Projects’.

For such a deep pursuit, the book is deceptively slim. It has eight sections, corresponding to the eight churches. Each section contains a prose piece and a verse piece, reflecting the structure of many of the Hawksmoor churches, with the church as their body (the chapter’s prose) and the pyramid sat outside the church its soul (the chapter’s verse).

The dreams of London that Sinclair tracks are disturbing. In its prose pieces, Sinclair’s mind is completely submerged in the unreality of the city that T.S. Eliot observed in The Waste Land. Illnesses such as hayfever are seen as potential communications from interstellar intelligence. The constant threat of some malignant existence underneath the churches stalks the quotidian descriptions of grass-cutting for the council in diaristic entries that make up a large portion of the text. The pentacle itself re-appears, especially with reference to the Tarot deck where it is a suit that reflects the material world, particularly that of finances. Twisted essayistic sections on everything from the intricacies of Egyptian autopsy rituals to Stan Brakhage to William Blake pass through the book like apparitions. Lines of force invading lines of text.

The verse sections are agnostic visions, relayed in rich free-verse that absorbs the daring of American poets Olsen and Dorn as well as Burroughs, and the great modern British poets David Jones and J.H. Prynne. In his phantomatic verse, Sinclair captures the amorphic soul that treads in the tower’s shadows, its complicated comorbid thirst for annihilation and for energy that stretch across time-continuums.

However, the quiddity that most runs through Lud Heat, much like Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow released two years earlier (which examined the rotting dream of the 1960s through the lens of World War II), is the assembly of a new order. The death of the sixties dream and what those dead dreams themselves would dream.

Sinclair reflects, “it was an endgame time. We were right on the cusp, because Thatcherism was on the horizon [she was elected Conservative Party leader the same year Lud Heat was published]. After I left and came back, all the gardeners had been dismissed and it had become a privitised thing. The gardens were done by a team that came from Bristol, just a bidder.” And even the Hawksmoor churches which had been decrepit for decades, “were cleaning up and made self-aware. The Ackroyd novel [the bestseller Hawksmoor released in 1985 and based on Sinclair’s theories] kind of symbolised the moment when it was no longer at all what it had been, when you could just wander in there.” The radical poets, led by Mottram, would also lose their grip of Poetry Review soon-after, in a period called the ‘Battle of Earls Court’ and the poetical status quo would return, like a scab grown over a gash.

Sinclair would say of 1975 that it was the going-out of a light of another world, “suddenly and noticeably it became harsher as an environment”. Inflation soared, grants were cancelled, public pay rises were frozen, and unemployment would rise in intermittent recessions.

Fifty years later, the shape-shifting text of Lud Heat continues to reveal itself to readers, including Sinclair himself. When talking about the book, you get the sense that as an author he is still chasing and making sense of his own vision. He explains, ahead of a 50th anniversary re-issue of the book, that when researching a recent exhibition (looking back at his 1974 exhibition) held at Swedenborg House that he “found quite a lot of strange things”.

He found an earlier poem “called Lluddheat all as one word”. He also found “drafts of this other whole bunch of poems that didn’t go into the book”. And when helping to sort out Catling’s papers after he passed, Sinclair found “loose sheets in some kind of pink folder with drawings or pictures stuck in it. So I got back a Lud Heat folder that had a whole bunch of stuff that never appeared in the book”. Sinclair will restore some of these poems to the never-settled poetic field of Lud Heat in the re-issue.

However, the true legacy of Lud Heat is that it never ended. Sinclair’s sacred geometry has engendered a new way to read the city. Grand London constructions such as Canary Wharf, the M25, the Millennium Dome, or the 2012 Olympic Park take on a new symbolism when you consider their place within the city and how it attempts to circulate or circumvent energy. A brand of investigative poetic journalism dressed in psychogeography’s clothes has continued to unsettle developers and policy makers in the dozens of books Sinclair has published since Lud Heat, reveling in the aphorism he states in Suicide Bridge, “myth is what place says. And it does lie.”

Ironically, the ascension of tall office buildings in the city means the sight lines of the churches are no longer visible today. And with the omnipotence of Google Maps as a means to navigate the city, many inhabitants are distanced from a naturally unfolding London. Because of that, fifty years later, Lud Heat feels even more vital. A way of understanding the symbols in the city that if read correctly flow like a text. Its caustic words remain like fire scars on the white pages of London; a reminder that something was once here and that something terrible had happened and is perhaps still yet to happen again. It is very much a book of its time, before its time, and radically outside of time.