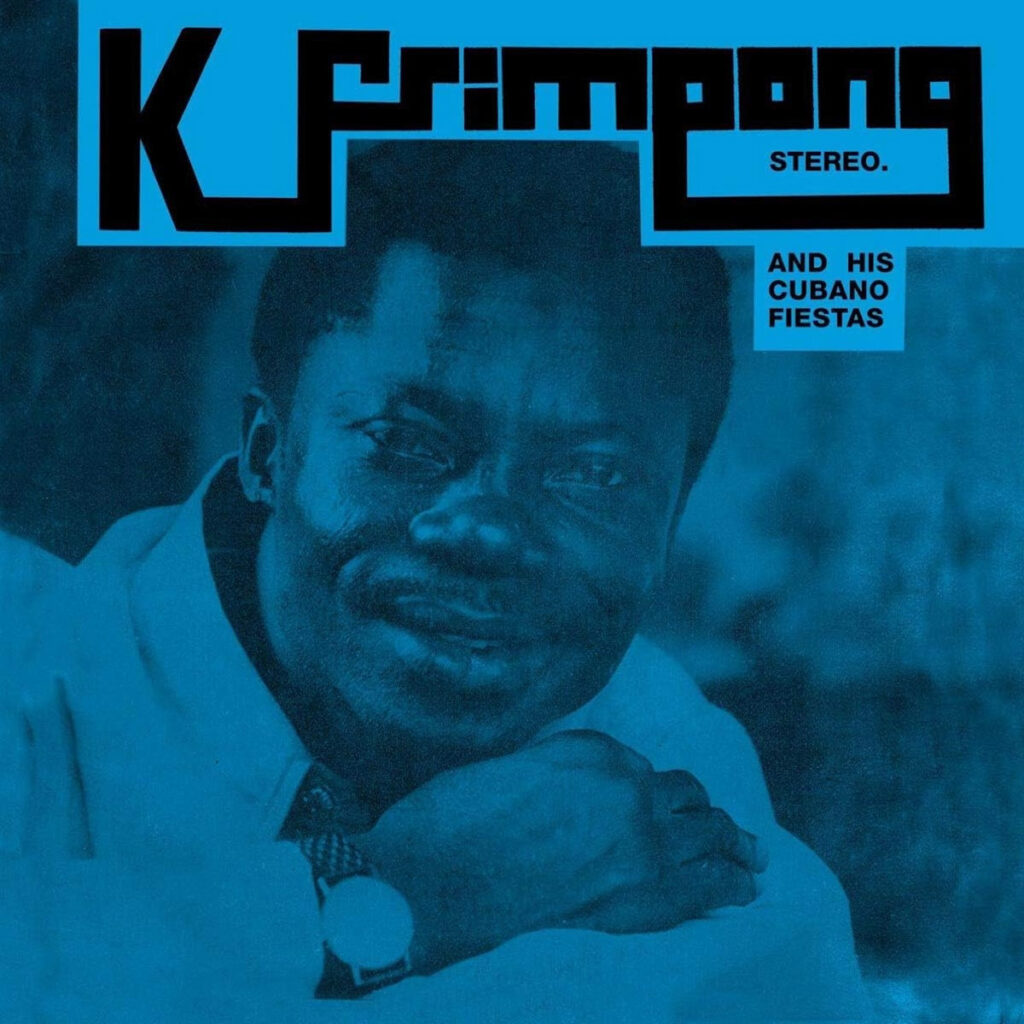

There are records that feel like postcards from the past, and there are records that feel like time collapsing in on itself, until it becomes alive again in the present. Alhaji K. Frimpong’s The Blue Album, recorded in 1976 with his band, the Cubano Fiestas, belongs firmly to the latter. To hear it now, almost half a century later, is to be reminded that highlife, Ghana’s musical gift to the world, was never static, never parochial, but a restless and adaptive language.

Born in 1939 in Ofoase, in Ghana’s Ashanti Region, Frimpong came up through the dance-band circuit of the 1950s, when orchestral highlife held sway in nightclubs and ballrooms from Accra to Kumasi. By the mid-70s, that refined style had been electrified and splintered: James Brown’s funk, American soul, the psychedelic expansions of Hendrix and Santana, the emergent Afrobeat of Fela Kuti, all filtered into Ghanaian studios and dancehalls. Frimpong, with his warm tenor and an ear for arrangement, was perfectly placed to navigate this moment of cross-pollination. He was not a polemicist like Fela Kuti, nor a strict traditionalist. Instead, his gift was in balancing emotional affinity with experimental expertise.

The Blue Album finds him at his creative zenith, flanked by one of Ghana’s most formidable outfits, Vis-A-Vis, temporarily renamed here as the Cubano Fiestas. Their chemistry is immediate: a rhythm section that shuffles and glides rather than merely keeping time; twin guitars in bright, interlocking figures; horns that blast not as punctuation but as commentary; percussion that is layered yet uncluttered. And then there are the synthesizers, used sparingly, almost mischievously, placing this record firmly in the 70s while hinting at futures yet to come.

At its centre lies ‘Kyenkyen Bi Adi M’awu’, a song that needs no introduction in Ghana, where it has become a standard, sung at parties, quoted in films, sampled by generations of musicians. Its refrain translates as “My love has left me, I will die”, a phrase that in lesser hands might tilt into melodrama, but in Frimpong’s delivery feels quietly devastating. He doesn’t wail or declaim; he sings with controlled ache, his voice threading through radiant horns and staggered percussion. It is heartbreak you can dance to, sorrow carried on syncopation. The emotional logic recalls American soul ballads, The Dramatics’ ‘In The Rain’ is a fitting parallel, yet here the ache is carried not by slow jams but by a highlife groove that demands movement. It is at once cathartic and communal, grief transformed into rhythm.

Elsewhere, the record deepens its palette. ‘Gyae Mensu’ is buoyant, propelled by feather-light percussion and saxophone lines that lift rather than weigh down. ‘Yaw Barimah’ and ‘Susu Ne Wonka’ draw from the Akan storytelling tradition, their parabolic lyrics set against mid-tempo grooves where guitar lines sparkle like kente threads under stage lights. The record is full of these balances: tradition entwined with experiment, melancholy shadowed by exuberance.

Side two of the original LP ventures further. ‘Baabi A Obi Awuo’ reintroduces the title phrase of ‘Kyenkyen Bi Adi M’awu’, but recast, refracted, stretched across new textures. ‘Afe Nkyere Ba’ builds around surging horns, the arrangement tipping towards chaos yet never losing grip – Afro-funk and highlife colliding, each instrument straining against the others in a glorious push-and-pull. ‘Obi Nim’ begins with lyrical guitar figures, soon enveloped by percussion that rolls like coastal waves, Frimpong repeating the phrase “Nobody knows” with a resigned insistence that feels both universal and personal. The closer, ‘Koforidua Nsuo’, is lush and declarative: guitars shimmer, synths hover at the edges, and Frimpong’s vocal rises with renewed confidence, as though the cycle of loss and longing that animates the record finds a fragile resolution.

Listening in 2025, one is struck not only by the craft but by the prescience. Many contemporary Ghanaian and Nigerian artists, from highlife revivalists to Afrobeats stars, are chasing a similar equilibrium: songs that speak to intimate truths while commanding dancefloors; grooves that carry heritage forward without calcifying it. The Blue Album anticipates this perfectly. You can draw a straight line from its textures to the digital warmth of today’s Alté movement, or to the sampled guitar licks in Afrobeats hits that nod knowingly to the 70s.

Outside West Africa, Blue stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the global canon of 70s fusion. Its rhythmic drive is kin to the Afro-jazz explorations of Cymande, its horn-led exuberance mirrors American funk collectives like The Headhunters, and its ability to balance the sacred and the profane recalls the deep soul of Al Green. Yet it is never derivative. This is distinctly Ghanaian music, rooted in the cadences of Twi, in the social function of proverbs, in rhythms designed not just for listening but for gathering.

Part of the album’s legend lies in its scarcity. Original pressings are vanishingly rare, with even 2011’s limited reissue quickly becoming a collector’s item. The market value speaks less to fetishism than to the hunger to access a work long trapped in private collections. This new reissue is thus more than an act of preservation; it is an act of restoration. The remastering lifts a veil: horns breathe, drums crack with clarity, guitars glisten. The soundstage is widened, and what was once muffled by age emerges anew, fresh without erasing its analog warmth.

The cultural timing is perfect. In an era when young African musicians command global charts, and when crate-diggers continually unearth hidden gems for re-circulation, Blue serves as both anchor and inspiration. It reminds us that the modernity of Afrobeats is not rupture but continuity, that today’s hybrids have long genealogies.

Ultimately, what makes The Blue Album endure is its humanity. It is a record about love, loss, resilience, community: topics that travel across languages and decades. Its genius lies not in virtuosity for its own sake, but in the way it gathers listeners into a shared emotional space. Whether you understand the lyrics or not, you feel the ache, the joy, the pulse. And as the final notes of ‘Koforidua Nsuo’ fade, you are left with the uncanny sensation that time has folded, that the Ghana of 1976 is still alive in your living room, club, or headphones.

Some albums are documents. The Blue Album is an atmosphere. To have it back in circulation, restored and resonant, is to be reminded of how porous music’s borders are, between past and present, Africa and the wider world, grief and joy. It is more than a reissue. It is an invitation to dance again with ghosts who were never really gone.