Anyone stricken with grief at the death of Ozzy Osbourne might have taken to their beds this summer to binge-watch The Osbournes. If they had, during episode 10 of the second season (which originally aired in February 2003) they might have made an interesting discovery. As Sharon Osbourne ventures into teenage son Jack’s disorderly bedroom and makes her way to the ensuite bathroom, she stumbles upon a discarded used condom packet in a plastic bag. But that’s not the interesting part. In front of her, unmistakable on the wall, is a black-and-white poster for the third Electric Wizard album, Dopethrone, released in 2000.

When Ozzy died, musician/producer-turned-YouTuber Rick Beato made a short video about the bands that had been inspired by Black Sabbath. He included a snippet of Dopethrone song ‘Barbarian’, a locked-groove monster of a track conjuring images of Conan on quaaludes. It helped Beato make the crushingly obvious point that Sabbath was an influence on Electric Wizard and the wider doom-metal scene. But back in the early 2000s, seeing the cover art of Dopethrone within the tacky Versailles-lite surroundings of the Osbourne mansion caused a ripple of excitement through the stoner underground. It raised the possibility that Ozzy might have heard the band thundering through the walls of his home, demanding that Jack turn that shit down. Or up.

“He [Jack] even put us in Entertainment Weekly,” says founding Wizard and guitarist/vocalist, Jus Oborn. “There was some article about rock music, and he was slagging off The Strokes, saying they were just fucking rich kids and he knew for a fact that their parents were super ultra rich. And he pulled out Dopethrone and said, ‘That’s a real band.’”

For all of young Jack’s faults, he knew a thing or two about heavy music. It aggravated me that after Ozzy died in July, so much of the discussion about his legacy dwelt on his working-class roots, as if that was the only interesting thing about him as an artist. Really, more should have been made about his vulnerability. From the opening line of ‘Black Sabbath’, through ‘Wheels Of Confusion’, and the song that started his solo career, ‘I Don’t Know’, Ozzy crafted a poetics of uncertainty. Tossed on the tides of stardom and addiction, he sang like he was holding on for dear life. “He made my lyrics sound as if they were coming from his soul,” Geezer Butler wrote in his recently published memoirs. Raw emotion suffused Ozzy’s otherworldly wail with urgency and drama. In the same way, Dopethrone feeds off a raw energy, but that energy is a deep-rooted misanthropy drawn from the injustices of being a heretical Englishman born under the yoke of someone else’s power.

As a quarter of a century has passed since the release of Dopethrone, we are in the midst of a struggle against cultural revisionism when it comes to the high-water mark of music at the turn of the century. Now, we are told, the early 2000s belonged to bands like The Strokes and The Libertines, via the confected retro fashion “indie sleaze”.

On the other side of the argument is the Ozzfest era (a festival with a largely American undercard beneath Sabbath and Ozzy solo, recreated for the Back to the Beginning concert), which helped launch the careers of nu-metal acts like Slipknot and System of a Down. Both these bands captured the very troubled spirit of the age when Iowa and Toxicity landed Number 1s in the UK within weeks of each other in August and September 2001. As bands like Korn, Limp Bizkit and Deftones grow ever more popular with new Gen-Z audiences, selling out arenas again and topping the charts, nu metal seems to have won the battle and the war with the indie of the period. Everyone still laughs at Fred Durst, but when he’s drawing the biggest crowd at this year’s Reading Festival (not known for its forty-something attendees), whereas Pete Doherty is struggling to climb higher up the Glastonbury bill than an early afternoon slot since morphing into Gérard Depardieu, maybe it’s time to have a proper debate about noughties music style over substance.

What does this have to do with Electric Wizard? As Oborn remembers it, bassist Tim Bagshaw and drummer Mark Greening of the original three-piece lineup that recorded Dopethrone pushed, and failed, to incorporate nu-metal elements into the band’s sound. But Dopethrone, like Slipknot’s Iowa, was a brilliant encapsulation of where the band was from. Just as Slipknot became synonymous with their home city of Des Moines, Electric Wizard became synonymous with the market town of Wimborne and its shadowy rural surroundings in South East Dorset. Both bands came under the influence of Harmony Korine’s film Gummo, released in 1997, depicting a savage and malformed underclass in Ohio. Slipknot used a sample of kids arguing drawn from the film as a kind of intro tape before they came onstage in their early tours. The film also resonated with the Wizard’s ambitions.

“We could do our English Gummo,” Oborn remembers the band discussing amongst themselves. “But with some occultism and having [nearby Iron Age hillfort] Badbury Rings in there. [It would be] formed of original ideas (I hope) of all these little environmental influences all nailed together.”

Dopethrone had an unmistakable English witchiness to it – a palpable aggression too. It reinvented doom metal, and eventually destroyed the first lineup of the band. It was written and performed with two musicians Oborn doesn’t speak to anymore. Its producer is dead. The band only now communicates with Rise Above, the label which released it, via lawyers. There was something cruel about the way Electric Wizard released this, the greatest album ever made, right at the turn of the millennium. They slammed the ledger shut after it had barely been opened. The three tours of North America the band made afterwards were a triumph, but sealed the original lineup’s fate.

It was in America, on the Seattle leg of that first US tour after the album was released, that Oborn met Liz Buckingham, guitarist of Sourvein and before that 13, in whose hands the future of the band resided. Today they are gathered around their kitchen table in their farmhouse on the moor in north Devon, where they now live as bandmates as well as husband and wife. They are trying to help me make sense of what attracted Americans to the Wizard’s “Dorset Doom”.

“It just seemed really English,” Buckingham says of Dopethrone. “Electric Wizard seemed different to the American equivalents. They just seemed like the type of people that you’d have similar interests with. It was nothing that freaky or strange. His voice sounded very English.”

“I sort of sound like an angry chav on the album,” Oborn responds.

“You definitely didn’t sound poncey. It sounded aggressive, it sounded like you were possibly singing stuff I didn’t know about, being from America. It was culturally different, and that’s fascinating when you’re from another country. It sounded angry the way I knew people in America were angry-sounding, but possibly for slightly different reasons. And it sounded very dark. And Americans sometimes view England as being all spooky. So, yeah, it had that angle as well.”

“We wanted to be English as fuck,” adds Oborn. “[Nottingham sluggers] Iron Monkey had done a couple of albums. And I thought that’s great and everything, but they were really picking up on the American scene. It’s very American-sounding. And I thought, [Dopethrone] is gonna sound fucking English.”

“You are conveying where you’re from and how you feel about people in your environment,” concludes Buckingham.

Electric Wizard was formed in 1993 and had their psychic breakthrough with 1997’s Come My Fanatics… Rise Above label owner and Cathedral frontman, Lee Dorrian, was shocked when he heard the final mixes: “I just got completely stoned and listened to it on my bed and thought it was the most amazing thing I’d ever heard.” Electric Wizard had a fraught relationship with where they were from, with each other, and the people around them. Their formative years saw them robbing off-licences, robbing graveyards, falling off churches trying to rob crosses, and, in Oborn’s case, trying to start a revolution by setting fire to a Robin Reliant outside Wimborne Police Station.

There were strange forces running through, and under, Wimborne. Isaac Gulliver, a notorious 18th-century smuggler, was one of its favourite sons. The band spied freemasons conducting nefarious rituals in their lodge; Nazi memorabilia hunters traded wares in the village hall; and bikers sold heroin in The Three Lions Inn. The markers of the old Georgian families who dominated the town were all around: both the imposing gothic observatory, the Horton Tower, and an ominous ornamental pagoda built by Edward Drax overlook the undulating landscape in Wimborne’s outskirts; in the apocalyptic new-age commune at nearby grade II-listed pile Gaunt’s House; and in the band’s interactions with its owner, Sir Richard Glyn, who once interrupted a squat jam waving a sword in a full suit of armour. This was all mixed in with a steady diet of video nasties (one being brutal 1970 German witch-finding exploitation flick Mark Of The Devil), weed (the original dopethrone was a temporary furnishing made of bars of cannabis in their home-cum-rehearsal space, “13”) and LSD (to stimulate bad trips, of course).

“It all seeped into Dopethrone,” says Oborn. “And seeped into the story. I mean, there are stories in there about the witchfinders. The rural abuse of power is captured in some of those lyrics. In ‘We Hate You’, definitely.”

Mass-shooting anti-anthem ‘We Hate You’ was so integral to the misanthropy of the album there were two versions on its demo. In the wake of Columbine it played like a bad-taste revenge fantasy, as dispassionate as the protagonists in Gus Van Sant’s 2003 film, Elephant: “So I’ll take my father’s gun and I’ll walk down to the street/ I’ll have my vengeance now with everyone I meet, yeah.” (Oborn liked to throw in an Ozzy-ish “yeah” when he could.)

“I always want the records to sound like a kind of film,” he says. “I think that’s where you take it back to Wimborne. I was never going to make a film at that point in my life. But I could write a book, or do a comic book, or do this sort of art, this album, and I guess the visuals were rolling in my head because of LSD and everything. We’d do albums that followed a storyline as such. So there’s a sort of intro, and then there’s the main themes, and there’s little side stories. Everything’s very visual as well. It has to be. We visualise an arc of where everything’s going and how it ends.”

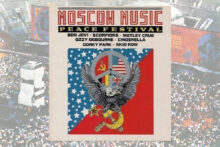

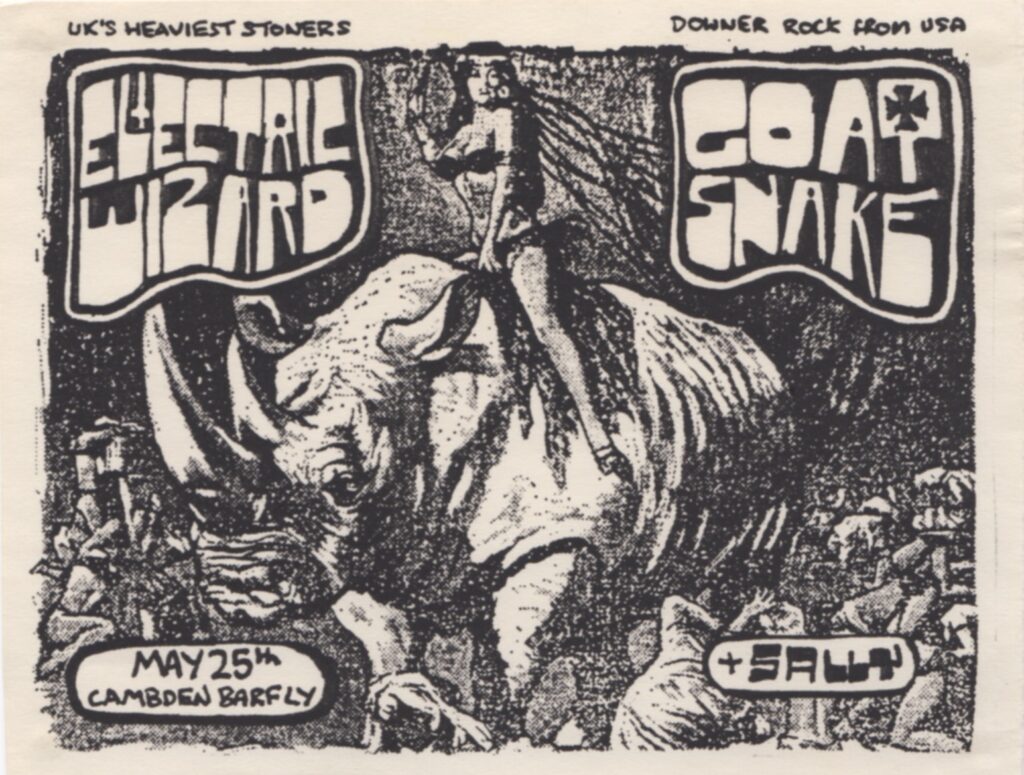

Despite practically dissolving after the release of 1998 EP Supercoven, the band was actually pretty sanguine going into the recording sessions for Dopethrone. They had just done a UK tour with Goatsnake, featuring Pete Stahl from American punk bands Wool and Scream on vocals, The Obsessed’s former rhythm section, and Greg Anderson on guitar – just before Sunn O))) became a thing. The first North American tour, partly facilitated by the latter, was also hovering. The Wizard went into Chuckalumba studio prepared, pumped up and ready to make the “heaviest album ever”.

Situated in the New Forest and run by John Stephens, Chuckalumba was little more than a cabin in the woods, or “garage in the woods,” as Oborn remembers it. Precious fragments of camcorder footage remain of the band tracking songs and listening back to mixes, and Oborn preparing the perfect bong, all captured by producer Rolf Startin, who also worked on Come My Fanatics… The band had originally found him in the Yellow Pages phone directory.

Startin liked the idea of recording in the middle of nowhere and as a group they savoured getting hands-on in the studio, having half-built Red Dog in Bournemouth for Come My Fanatics… themselves. Chuckalumba had a rough, uncluttered vibe which suited Oborn more than the poorly lit studios of the time which often smelled, in his words, like a “paedo’s fucking limousine”. Dopethrone’s sound is unmistakable and has never been successfully imitated (though Swedish stoners Monolord have come closest to capturing a similar guitar tone, on 2015’s Vænir). Oborn puts that down to tracking the album live (“recording live is the most important thing, ever”), as it happened, right in front of a giant poster of The Blair Witch Project.

“It’s probably just circumstance, you know?’ he says. “I mean certain elements, maybe the fact that it was recorded on a hard drive, like a really early hard drive, right? Rolf had a lot of compressors and stuff. So that might have helped with that just really raw, really nasty and cold sound. But then we bounced it down to tape for the mixes.”

“Maybe it’s the fact that all of you were pushing to be louder, louder, louder, louder,” laughs Buckingham.

The band’s cockiness was partly down to the quality of the material they had written, even if their partiality to chaos meant they put songs together in the studio. ‘Weird Tales’ was a melding of a Celtic Frost-style thrash opening (the band still uses ‘Procreation (of the Wicked)’ as an intro tape live), to a vast, loping riff that Tim had used on a demo featuring extensive samples from Scorsese’s The Last Temptation Of Christ. The band wanted to incorporate more psychedelic textures to the outro of the song, but Startin put his foot down at having too much “hippy shit” on the album, compromising on an elongated drone more in keeping with the synth innovations of Wendy Carlos or Klaus Schulze.

In general though, Startin was onside with the mission, open to ideas, and against the “antiseptic” feeling of modern heavy recordings. Startin sadly died of cancer a few years ago, and Oborn credits him with helping achieve the otherworldly genre upheavals of Come My Fanatics… and Dopethrone, which they themselves didn’t fully appreciate at the time. The band improvised constantly in the studio, so ‘I, The Witchfinder’ began with another of Bagshaw’s riffs before transitioning into one of Oborn’s appallingly heavy jams. There’s a strange freeform ferocity on Dopethrone; a kind of callous freedom.

Oborn tracked his guitar live with Bagshaw and Greening. Then he would double-track a second guitar and solos. Then he’d smoke some more weed and see where the wind took him – a wah solo here maybe, some other weird noises there. There are sections of the album with lots of overdubs which gives it the dense, swirling, Cyclopean-abyss feeling which resonates with the lyrical references to H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard and Arthur Machen. It was topped by his vocals, slathered in their own distortion – edgy, and holding the listener at arm’s length.

The film and TV samples sewn through the album behave like subliminal messages. As the title track seems to have come to a close, it collapses in again, slowed to a monumental hulk. Buried deep in the mix is the kiss-off line spoken by Vincent Price’s Prince Prospero in Roger Corman’s 1964 film version of The Masque Of The Red Death, as he duels verbally with Jane Asher’s innocent character, Francesca.

“Can you look around this world and believe in the goodness of a God who rules it? Famine, pestilence, war, disease and death – they rule this world,” declares Prospero.

“There is also love and life and hope,” Francesca responds, somewhat over-optimistically.

“Very little hope, I assure you,” he says. “No, if a God of love and life ever did exist, he is long since dead. Someone, some thing rose in his place.”

In a world where God is dead, let us worship marijuana (and Satan) instead, the song ‘Dopethrone’ insists.

Over in New York, Buckingham had been introduced to the band by visual artist Arik Roper, responsible for refining the aesthetic of the stoner-doom music scene there at the time.

“I knew about Rise Above for years,” she says. “And I heard he [Lee Dorrian] was releasing records by a new generation; this was a new sort of doom, as opposed to the early stuff. I couldn’t get Electric Wizard anywhere in New York. And then, as I was friends with Arik, he made me a mixtape, and I was like, ‘What?! This is the heaviest shit I’ve ever heard!’”

The connection between Oborn and Buckingham was instant when they met on Wizard’s first tour of America in the spring of 2001. But the subsequent two tours put a massive strain on the original threepiece, culminating in furious sessions for Dopethrone’s follow-up, 2002’s Let Us Prey, where they went into the studio and simply argued until something happened.

When that lineup finally – and in typical Wizard style, slowly – imploded, Buckingham answered Oborn’s call to join the band. In doing so, she provided a second guitar that let the band emulate their studio sound in the live environment.

“The band went instantly off the rails after Dopethrone anyway,” says Oborn. “I mean, everyone hated Let Us Prey. The wheels came off immediately. So Liz coming in was like, ‘Something’s fucking wrong. What the fuck happened here?’ It was getting back on track again.”

Buckingham sees her role as partly keeping Oborn on the straight and narrow of the doom-metal path. He has a tendency to explore, and sometimes alter things, to suit other musicians in the band: “But it’s good, because then we compromise with each other,” she says. “I like doom, y’know.”

When the band opened their recent album of re-recorded old songs with ‘Dopethrone’, in Oborn’s eyes it was a way of baiting people to listen to it just to see “how shit it sounds”. Black Magic Rituals & Perversions Vol.1, released last year, starts with ‘Dopethrone’ and ends with ‘Funeralopolis’, the second song on Dopethrone. The latter song has ended their live shows for years. If you had to distil Electric Wizard down to one song, it would be ‘Funeralopolis’. With lyrics drawn from his father’s experiences at the local slaughter house in Uddens Cross, and filtered through the anarchist, anti-capitalist prism of Napalm Death (who teenage Oborn used to jump on the train to the Midlands and visit), ‘Funeralopolis’ remains Dopethrone’s calling card.

“It was certainly intended to be a very epic riff type thing,” says Oborn. “And once I had the breakdown for the melodic first riff to the second riff – the ultra melodic intro, and then it breaks down into something discordant – then I was like: ‘Fucking… this is it. I’m on the money now!’”

The song had a performative effect on Oborn’s career as part of one of his most successful albums. Its impact meant he could eventually leave the system behind entirely: “One of the main things about doing Dopethrone, and its legacy, is that now I don’t have to do a day job. I can live off of a legacy. And that is something: I don’t want to fucking have to work.”

“I still rate it, not that I’m allowed to listen to it,” smiles Buckingham.

The raging finale of ‘Funeralopolis’, where Oborn gleefully screams for nuclear armageddon, seemed fantastically OTT in 2000. The trouble now is how relevant it sounds twenty-five years later. Like the album’s film samples, Dopethrone has had a subliminal effect on our culture. The simple rawness of its cover (digitally rendered by Bagshaw’s brother, Tom, from an illustration by Oborn) – Satan smoking a bong, king of all that he surveys – was intended to look like a spraypainting on a surfer’s van; something Boris Vallejo might have conjured if he read more Lovecraft. Designer Hugh Gilmour also worked on Dopethrone’s layout, just as he did with the late-nineties Sabbath reissues, further strenghtening the ties between the bands. There was nothing esoteric or hard-to-fathom about the cover of Dopethrone. Whether it’s on Jack Osbourne’s wall or on YouTuber critic Anthony Fantano’s shelves as he gives one of the recent Wizard albums a lukewarm review, it seems to crop up again and again, in the background, or just in the corner of your eye: malign, powerful, unmistakable.

It represents a hidden, alternative history to popular culture in the 2000s, running counter to a mainstream that foregrounded landfill indie bands playing live on TV in a shitty club on a redundant television channel like More4.

“Somewhere along the line, the journalists and press in England, especially, started just becoming trend setters,” laments Oborn. “Telling everyone, the fans, what they should listen to, rather than reporting on what people actually liked.”

When Oborn saw the reformed Black Sabbath headline Ozzfest ‘98 at Milton Keynes Bowl, Sabbath were in their early fifties, and actually slightly younger than he is now. Dopethrone was an album he expected to catapult Electric Wizard into the big leagues, but instead it destroyed the band… slowly. What came after with Buckingham was a steady, sure-footed realisation of Electric Wizard’s true potential. Dopethrone is Electric Wizard’s masterpiece, made almost despite themselves, and it killed the entity that created it. And so it remains, like a cursed child wandering the earth. In a world ruled by famine, pestilence and war, something even more powerful rose in its place: the new Electric Wizard. But that’s another story.