“And I will raise my hand up into the nighttime sky / And count the stars that’s shining in your eye / And just to dig it all and not to wonder, that’s just fine / And I’ll be satisfied not to read in between the lines…”

Van Morrison, ‘Sweet Thing’, 1968

“If you don’t like it, go fuck yourself…”

Van Morrison, on-stage audience interaction, 1974

There’s a story about the young Van Morrison that feels pertinent to this list: while living in Belfast, a love-struck Van went through a period of crouching inside dustbins in order to surprise – and presumably endear himself to – a girl he was especially besotted with at the time. (A girl who, unsurprisingly, did not find Morrison’s behaviour especially enticing.) It’s worth mentioning that this was not the misguided wooing technique of a gormless adolescent. At the time Morrison was amorously flinging himself out of dustbins, he was in his early twenties, had already toured America with his R&B band Them (experiencing commercial success with ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’, ‘Here Comes the Night’ and ‘Gloria’), and was back in his hometown, kicking his heels as he contemplated his next move. That his peers did not consider this business with the bins particularly uncharacteristic, says a lot about the young Van Morrison’s reputation. And while it is easy to laugh, his behaviour is so very quixotic, so very gauche and so very strange, that the primary emotion evoked must surely be one of pity, rather than ridicule. Van Morrison, it seems, has always been a somewhat unusual individual.

Born in 1945 into overwhelmingly Protestant east Belfast and brought up by a Jehovah’s Witness mother and an atheist father, Morrison is a mass of contradictions and peculiarities, a man who decries all the trappings of “showbiz bullshit” while striding onstage in trademark shades and trilby to sing into a monogrammed microphone (as his bandleader announces, “Ladies and gentlemen, Mr Van Morrison! VAN MORRISON!”) A man who is open about his musical influences yet bristles at anyone having the audacity to be influenced by him (“copycats ripped off my songs” he moaned in 1986’s ‘A Town Called Paradise). A man who claims to have experienced astral projection, who has dabbled in Scientology, New Age mysticism, Gestalt therapy and the white magic teachings of Alice Bailey. A man whose reputation largely rests upon his remarkable voice – a voice often praised as beautiful, when at times it can sound downright harsh and ugly: as if wrung from a gut seething with an inarticulate rage at the world. A man who treats journalists with the arrogant disdain of Lou Reed, and his band members with the capricious ruthlessness of Mark E. Smith. A man who is capable of making some of the most beautiful music ever heard and who, by most accounts, is a thoroughly unpleasant individual.

This strange, ill-tempered behaviour tends to either be dismissed by critics as Morrison being nothing but a diva, or else excused by fans as the price of genius. In fact, his behaviour is so consistently eccentric that it could well point to a deeper strangeness of character – a strangeness possibly beyond his control – a strangeness which quite frequently breaks out into his music. (And given today’s greater understanding of issues concerning mental health, it seems curious that this is a topic largely untouched upon in the various biographies and critical studies.) The following 10 tracks, then, are instances where Morrison’s muse and singularity of character take his music into weird, uncharted waters; where his inherent strangeness enhances the music rather than detracts from it. With this caveat in mind, there is nothing from 1967’s 31-track contractual obligation album, which Morrison recorded in a matter of hours in order to free himself from the Bang label, and contains such off-the-cuff “classics” as ‘Blow Your Nose’, ‘Nose In Your Blow’, ‘Want A Danish’, and the immortal ‘Ring Worm’ (“I can tell by your face / you’ve got ring worm / it’s a very common disease”); nor is there anything from 2021’s double album, Latest Record Project Vol.1 – where the banal meets the unbalanced and whose conspiracy-theory-heavy songs include ‘Why Are You on Facebook?’, ‘They Own The Media’ and ‘Stop Bitching, Do Something’. Nor is there anything from 1968’s Astral Weeks: a whole suite of such strange and beguiling beauty, it is impossible to parse.

The fact that all 10 of these tracks are from the last century is not to say that his more recent albums are devoid of strangeness or possess no moments of beauty. True, one has to sift through a slew of slickly rendered blues workouts to uncover these moments of beauty, but they are there. Unfortunately, though, the strangeness has calcified – or curdled – into an uncomfortable misanthropy that tends to surface solely in his lyrical concerns (the unbearable pressures of fame being an unbearably solipsistic leitmotif) rather than in the warp and weft of the music where it once ran riot, leaving audiences reeling, struck dumb, open-jawed – or at least scratching their heads…

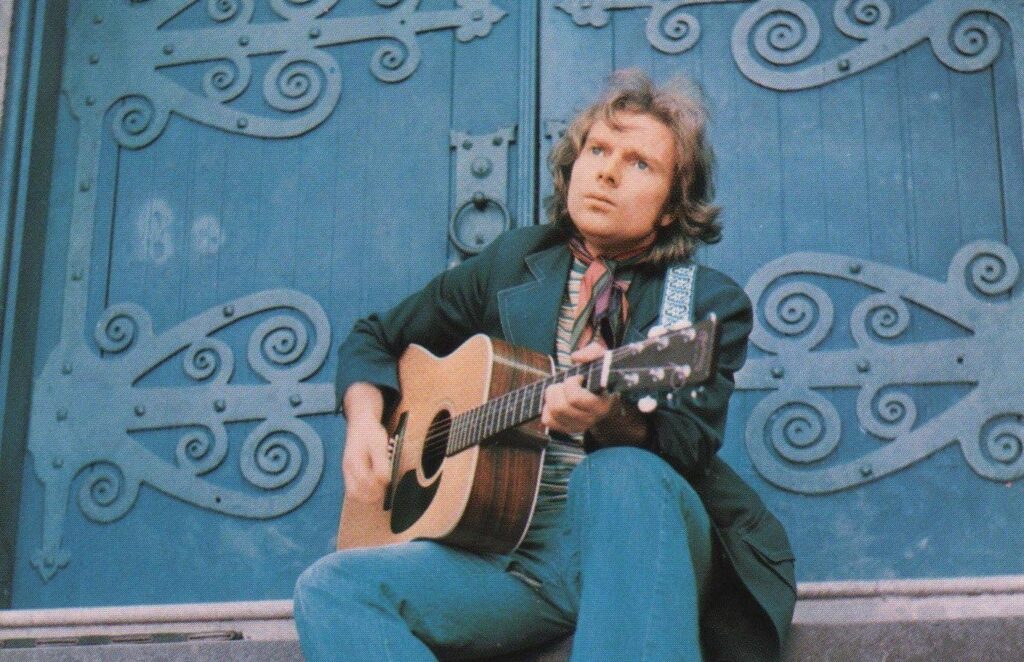

‘T.B. Sheets’, from Blowin’ Your Mind! (1967)

One of the very first songs Morrison recorded as a solo artist in New York in March, 1967, ‘T.B. Sheets’ is a harrowing 10-minute-meditation on watching someone dying from tuberculosis. Lyrically it is an intriguing juxtaposition of blues tropes (“It ain’t natural for you to cry / way in the midnight through / until the wee small hours / long ‘fore the break of dawn, oh Lord”) and sudden specific detail, bringing the song into dreadful focus (“I want a drink of water / I want a drink of water / I went into the kitchen to get me a drink of water”). The relentless see-sawing of the two chord groove lulls the listener into the same head-space as the singer: sat in that “cool room”, desperate to leave but unable to escape (snared there – by love? by duty? by a shamefully morbid interest?)

The surrendering of words for impressionistic sound is Morrison’s own form of scat singing: usually signifying an attempt at expressing something so sublime that words literally fail and are transcended for that “inarticulate speech of the heart.” In the case of ‘T.B. Sheets’, though, rather than transcend meaning, the wordless snuffles following the desperate line “open up the window and let me breathe!” seem to signify a degeneration – a visceral sinking into the subject matter of the song – in much the same way that the sound of a fellow-patient’s cough in Thomas Mann’s tubercular classic, The Magic Mountain, makes the protagonist of that novel feel “as if [he] were looking right down inside and could see it all – the mucus and the slime.”

‘Caledonia Soul Music’, outtake from His Band And The Street Choir (1970)

With a stubborn determination to allow no-one to categorise his music other than himself, in the early 70s Morrison described his own distinctive mix of soul, folk, jazz, R&B and country as Caledonia Soul Music – this cryptic moniker deriving from the theory that the roots of the blues come not from Africa, but can be traced back to the folk ballads of Scotland and Northern Ireland, with the songs carried across the Atlantic to the Appalachian Mountains by the Celtic settlers. How much of this theory can be heard in the piece of music that bears its title is questionable. Less questionable, though, is the languid loveliness of said piece. An outtake from 1970’s His Band And The Street Choir this unreleased instrumental rolls along for 18 hypnotic minutes, while Morrison limits his vocal contributions to the to the occasional grunt, hum or sigh – or to the issuing of musical direction or words of encouragement (“Make it melt… get some horns… you got it” etc). Think a stoned ‘In C’ or a rootsy Tubular Bells. (Morrison would later christen his touring band of 1973 The Caledonia Soul Orchestra.)

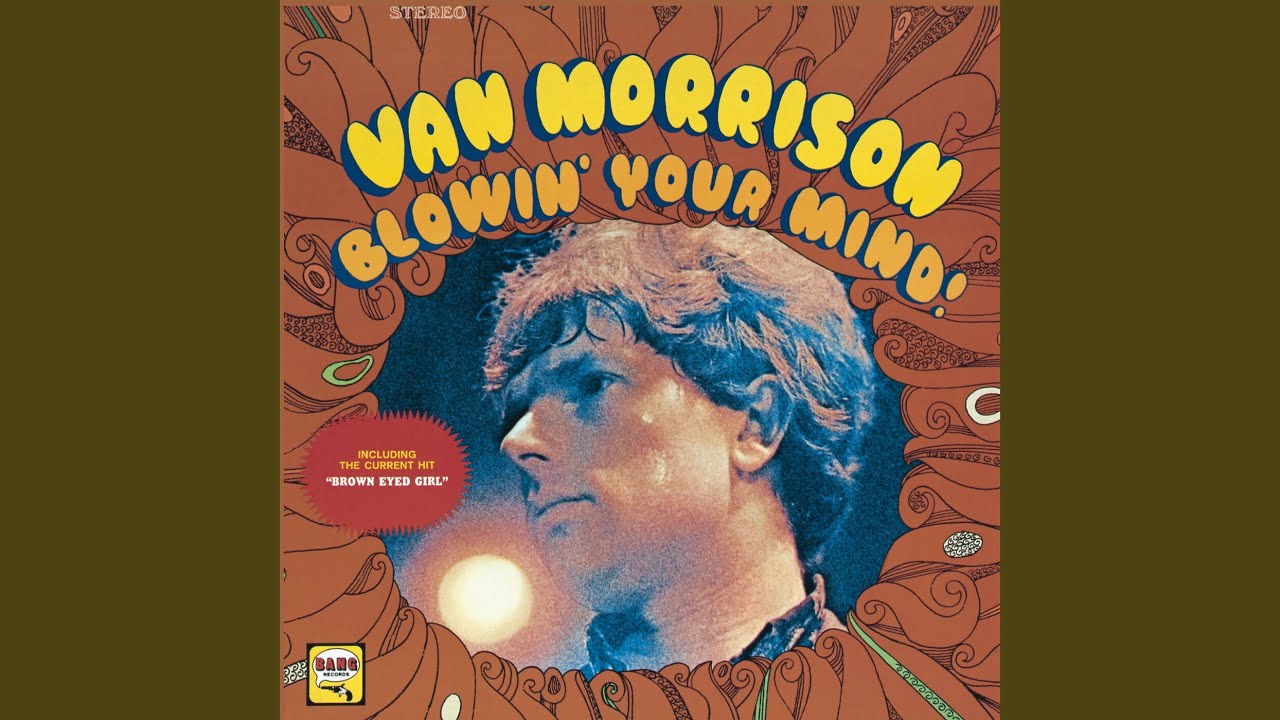

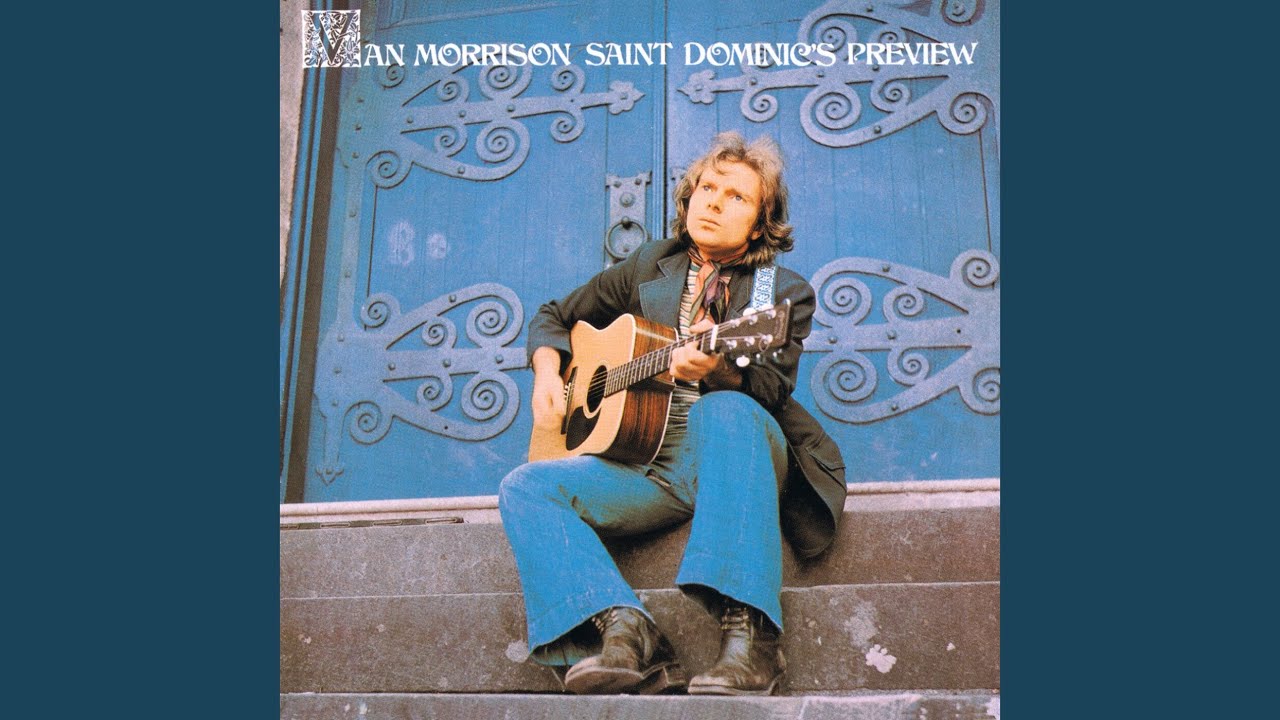

‘Almost Independence Day’, from Saint Dominic’s Preview (1972)

The 10 minute song that closes Morrison’s 1972 album, Saint Dominic’s Preview, begins with a spot of bluesy guitar noodling, giving way to a two chord strum, beneath which a Moog drones ominously while the singer claims to “hear them calling from Oregon” and to be able to “hear the fireworks up and down the San Francisco Bay” (the sound of which Morrison pleasingly replicates on his acoustic guitar). On a first listen, then, ‘Almost Independence Day’ seems to be an attempt to capture a moment in time. (The freezing of significant moments into an eternal present is one of Morrison’s key obsessions.) But if we scratch the surface, a possible deeper meaning begins to emerge. Morrison has said that the inspiration for the opening line (“I can hear them calling”) came from nothing more mysterious than a phone-call he received from one of his ex-bandmates from Them. But it’s interesting to note that it was after a 1966 Them show at San Francisco’s Fillmore, that Morrison was introduced to his future wife, Janet “Planet” Rigsbee. Add to this the fact at the time of writing and recording this song Morrison and Rigsbee were experiencing problems in their marriage and would be divorced within the year, the song suddenly becomes more than a disinterested account of a single night. Its meaning potentially widens to encompass a maelstrom of conflicting associations around beginnings and endings; nostalgia and regret; of an independence both longed for and dreaded. Even the title’s modifier, “Almost”, inserts a feeling of doubt or nervousness about this independence, in much the same way the celebratory fireworks are undercut by the Moog’s fog-horn drone. The result is an intimate minimalist epic of a lost past and an uncertain future.

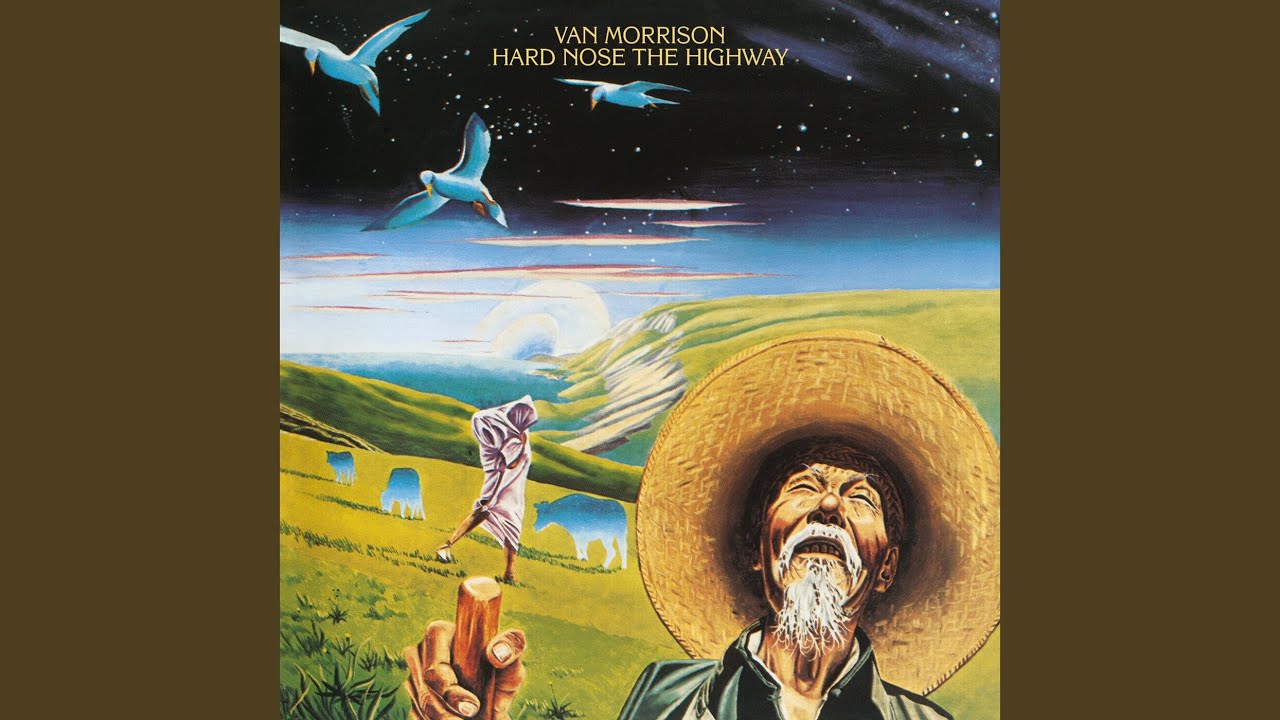

‘Snow In San Anselmo’, from Hard Nose The Highway (1973)

As befitting the truly bizarre cover art (courtesy of Rob Springett) the opening track on Van Morrison’s 1973 album, Hard Nose The Highway, is one of the strangest songs in his back catalogue. Like ‘Almost Independence Day’ the song initially seems to be another attempt at capturing a singular moment: in this instance, the rare sight of a snowfall in the California town of San Anselmo. And yet the song is laced with a plethora of drug references, suggesting, perhaps, an individual lost in some snow-bound San Anselmo of the mind. (As well as the titular “snow” we also get “if you suffer from insomnia / you can speed your time away” and “the waitress said it [I?] was coming down”.) And then there’s the arrangement, which is the wildest of Van’s career, featuring sudden unexpected lurches in tempo, a wailing sax break and, most strikingly, the shrill backing vocals of the Oakland Symphony Chamber Chorus.

Teetering on the brink of ridiculousness, ‘Snow In San Anselmo’ is a 4-and-a-half-minute pocket prog symphony, which manages to maintain its balance through the sheer bloody-minded commitment to the material from all of its players.

‘Bulbs’, from Veedon Fleece (1974)

After the collapse of his marriage, Morrison broke up what was arguably his greatest band, The Caledonia Soul Orchestra, and returned to Ireland for a month-long holiday/convalescence. While touring the Republic (pointedly staying out of Northern Ireland) Morrison wrote much of the material for his second solo masterpiece, 1974’s Veedon Fleece – the album on which Morrison has come closest to recapturing the strange uncanny magic of Astral Weeks. Indeed, Veedon Fleece is where Morrison’s strangeness is given free rein: an album of such mystifying rough-hewn beauty that we are spoilt for choice when it comes to selecting a single track. But let’s go with ‘Bulbs’, the chorus-free single that opens side two, in which Van somehow manages to imbue the opening line – “I’m kicking off from centrefield” – with such emotion that it’s one of the most poignant utterances of his entire career. At another point Morrison decides to growl and grunt his way through a verse like a dog, which, frankly, sounds as if he has simply forgotten to write any words, but which nonetheless still manages to be strangely moving.

‘Try For Sleep’ and ‘Twilight Zone’, from The Philosopher’s Stone (1988)

Recorded in 1973 and 1974 respectively (and both unreleased until 1998’s outtakes collection, The Philosopher’s Stone), the subject matter, music, and Morrison’s impressively sustained, Sly Stone-quoting falsetto, reveal these two songs to be cut from the same crepuscular cloth. And when yoked together they create a long, dark, horny night of the soul, in which the insomnia of ‘Try For Sleep’ drifts into the fugue-like (or post-coital?) state of the ‘Twilight Zone’. Most out-there moment? Either ‘Try For Sleep’s’ proto-Prince lyric “I feel it when you touch me / I’m already wet” or ‘Twilight Zone’s’ quite filthy-sounding refrain of “HONEYCOMB!”.

‘It’s All In The Game’ / ‘You Know What They’re Writing About’, from Into The Music (1979)

For 1979’s Into The Music album, Morrison recruited James Brown’s one-time saxophonist and band-leader, Pee Wee Ellis – whose impact on Morrison’s music for the next few years would be considerable. Here, what begins as a soulful cover of Tommy Edwards’s 1958 hit, ‘It’s All In The Game’, suddenly slips free from its tethers and morphs into Morrison’s own ‘You Know What They’re Writing About’: a seemingly improvised coda of ‘Horses’ meets ‘Jungleland’ proportions in which Morrison implores his beloved to meet him – to meet him – to MEET! HIM! – “down by the pylons.” Throughout the song Morrison’s vocals flit between beauty and ugliness – often in the same line, sometimes from one syllable to the next. It is an extraordinary vocal performance.

‘When Heart Is Open’, from Common One (1980)

With Pee Wee Ellis now fully on board, Morrison recorded his 1980 album, Common One over 11 days in a converted (and apparently haunted) monastery high up in the French Alps. Morrison had evidently been listening to Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way because that proto-fusion classic is all over Common One – but is especially noticeable on this closing track. According to Ellis, the song was improvised and recorded on the spot, with no real direction from Morrison aside from informing the band that there was neither key nor tempo and that he wanted something “different” from the “normal stuff.” The result is 15 minutes of minimalist ambient jazz, over which Van recounts another of his mystical visions, until, once again, he is transported beyond mere words and is reduced to whinnying into his harmonica like an animal in pain and/or ecstasy.

‘Song Of Being A Child’, from The Philosopher’s Stone (1988)

Austrian writer, director and Nobel Prize winner, Peter Hanke, co-authored Wim Wender’s 1987 masterpiece Wings of Desire, in which benign angels watch over the troubled inhabitants of Berlin. Hanke’s poem, ‘Song Of Being A Child’, features heavily in the film, and it must have made an impression on Morrison, because that same year he recorded his own version as a spoken word duet with his backing singer, June Boyce. What makes this piece so singular is the incongruous juxtaposition of Morrison’s almost-angry-sounding Belfast brogue and the tender verse (which harks back to Morrison’s own preoccupations with the innocence of childhood) and a musical backing that’s not a million miles away from Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works Volume II. Again, it shouldn’t work, and yet…

‘In The Days Before Rock ‘N’ Roll’ from Englightenment (1990)

1990’s Enlightenment is a warm collection of subtly arranged gossamer-light pop songs. Free of bile and misanthropy, it sounds like the work of a happy man – or at least a man finally comfortable in his own skin. (Naturally it wouldn’t last.) And while there is nothing on Enlightenment that’s going to spook the horses, it does contain one of Morrison’s last successful forays into outright strangeness. What could be a perfectly fine panegyric to the pre-rock & roll radio of Morrison’s childhood slips into the realms of the strange by the contribution of Irish poet, Paul Durcan, and his eccentrically delivered spoken-word co-vocal (especially the opening innuendo of “I am down on my knees / at the wireless knobs”) and Van’s own free-form observations about betting on “Lester Piggot, 10 to one!” and “let[ting] the goldfish go.” The closest Morrison has come to releasing a novelty song, ‘In The Days Before Rock ‘N’ Roll’ skips past this derogatory prefix down to the sincerity of both performers: the expression of serious joy.