It should probably be said, up front, that emo isn’t a genre. It doesn’t refer to one specific sound, era, or movement. The term sprang out of Washington D.C’s mid-80s hardcore punk scene as shorthand for “emotional hardcore”, but it didn’t really mean anything. It was just semantics – a militant’s way of distinguishing newer, more outwardly vulnerable bands like Rites Of Spring from slightly older, more traditionally “masculine” bands like Black Flag. It was a tongue-in-cheek insult either laughed off or shot down. In a now infamous rant onstage with Embrace in 1986, Ian MacKaye called emocore “the stupidest fucking thing I’ve ever heard in my life”.

Still, “emo” stuck around. In the 90s, it snowballed into a predominantly American subculture, with a thriving DIY economy and a ‘look’ that skewed geek chic. In the 2000s it metastasised into a global youth culture, with major label backing and a more goth-leaning aesthetic fuelled by clothing lines at Hot Topic. Today, emo’s fingerprints can be identified everywhere from digital subcultures like hyperpop to the highest-grossing echelons of the music industry (after bringing out Billie Eilish at Coachella in 2022, Paramore spent most of 2023 and 2024 on the road with Taylor Swift).

Emo spans decades and generations; encompasses everything from Fire Party to Fall Out Boy, American Football to Juice WRLD. It has been rejected by musicians, embraced by fans, defended by purists, and mass marketed as a lifestyle. These days, you could reasonably call it an identity – a collection of artists, sensibilities and sartorial choices that, when arranged a certain way, form what “emo” is in the cultural imagination. It’s tricky, then, to pick a definitive three album run in a genre that doesn’t really exist. However, there are runs that pin-point key moments in emo’s ongoing evolution.

You could make a case for My Chemical Romance’s first three albums (I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge, The Black Parade), which mark emo’s sonic transformation in the 21st century, from scrappy post-hardcore to Kohl-eyed rock opera. You could tell a more contemporary story with Paramore’s releases between 2009 and 2017 (Brand New Eyes, Paramore, After Laughter), which carried emo out of its adolescent Warped Tour phase through to indie maturity and, ultimately, pop sensation. Or, you could look further back to Jawbreaker’s early-to-mid-90s progression of Bivouac, 24 Hour Revenge Therapy and Dear You, whose heart-on-sleeve lyricism and sensitive machismo helped lay the blueprint for commercial emo to come. Following that thread into the 2000s, the first three albums by Long Island “rivals” Taking Back Sunday and Brand New represent emo’s most memorable songwriting at its highest point of saturation. None of these, though, reflect emo’s multi-generational range.

Released between 1996 and 2001, Jimmy Eat World’s second, third and fourth albums – Static Prevails, Clarity and Bleed American – bridge emo’s past and present. They illustrate its story as a cultural sensation: how it got swept out of suburban basements, boosted by burgeoning social media, and elevated into a significant force in the music industry. These three albums chart Jimmy Eat World’s mid-90s ascent, major label disappointment, and mainstream breakthrough in chronological order, but they also mirror emo’s journey from a DIY network, to a trend, to an international phenomenon.

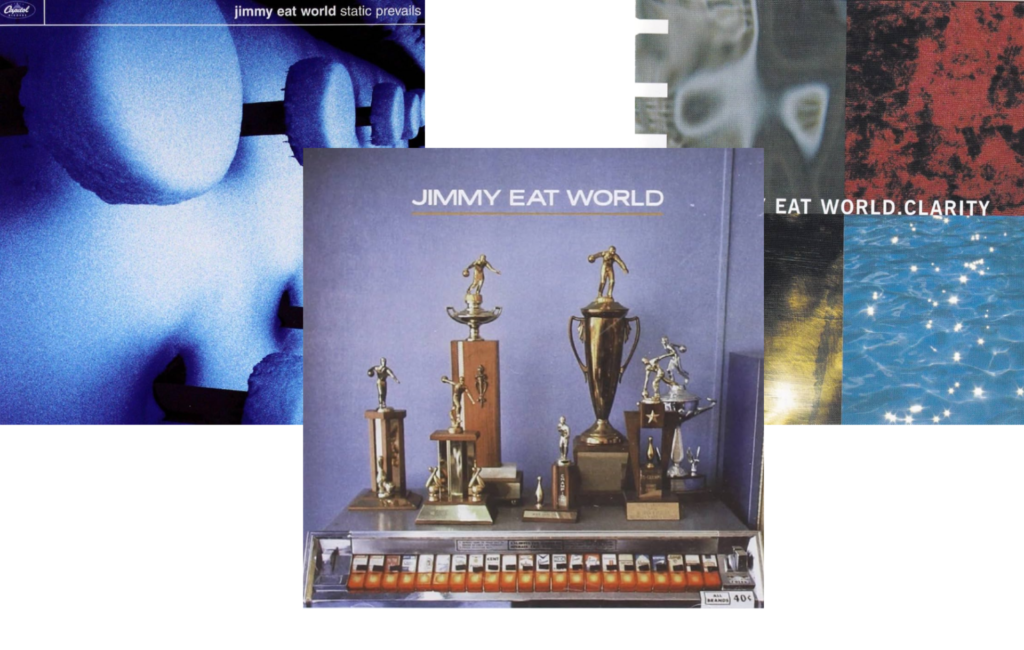

When they started playing shows in 1994 in their hometown of Mesa, Arizona, Jimmy Eat World were a skate punk band. Their self-titled debut is full of high velocity riffs and raspy shout-singing by guitarist Tom Linton, who handled lead vocals on most tracks. They evolved quickly from there. Linton split vocals with (now frontman) Jim Adkins, who has a higher, cleaner register, and they began to fall in with the developing “Midwest emo” scene, touring and putting out splits with cornerstone bands like Christie Front Drive, Jejune, Sense Field and Mineral. Meanwhile, following the success of Nirvana earlier in the decade, A&Rs were criss-crossing North America looking for the next alternative success story. With their accessible songwriting, direct lyricism and clean-cut good looks, Jimmy Eat World seemed like a solid bet. Capitol signed them in 1995 and put out their second album Static Prevails a year later.

Combining the driving energy of their debut with the raw feeling and quiet-loud-quiet dynamic typical of 90s emo, Static Prevails catches Jimmy Eat World in transition. Sounding more like a Sunny Day Real Estate homage than the breakneck Fat Wreck Chords-era punk band they started out as, the instrumentals are more textured, the pace a lot slower, the vibe more anguished. Linton and Adkins split lead vocals, with Lindon’s rougher tone helming the more radio-friendly tracks like ‘Rockstar’ and ‘Seventeen’ that bear more resemblance to their earlier style, while Adkins’ fragile scream cracks and careens off key on slowburn tracks like ‘Claire’ and ‘Digits’, signposting the direction they were heading in.

As major label debuts go, Static Prevails was unsuccessful. It was met with mixed reviews, sold less than 10,000 copies in its first release, and it wasn’t exactly what Capitol had in mind when they signed Jimmy Eat World amid a surging market for pop punk. The fact that of all their albums it shares the most DNA with 90s emo make Static Prevails a cult favourite among a niche section of Jimmy Eat World’s fanbase, but there’s no question that it wears its influences on its sleeve more than it offers a sound of their own. The songwriting is infectious but inconsistent; a crucial but unsteady step between their origins and their future.

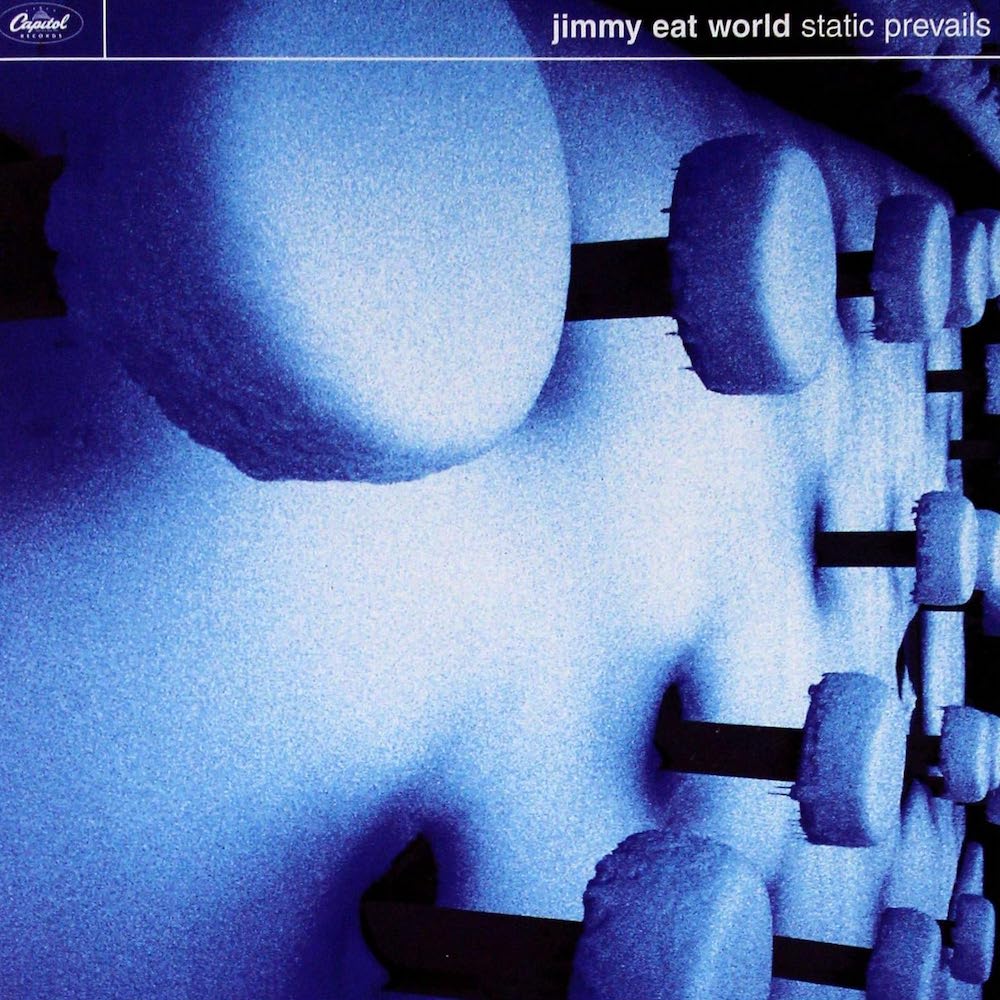

If Static Prevails is the sound of Jimmy Eat World finding their feet, then 1999’s Clarity is the gun shot as they bolt from the starting line. After the commercial disappointment of Static Prevails, the band knew their follow-up would be subject to higher expectations. They also figured it would be their last chance to take a major label budget and run with it before being dropped, which is exactly what happened.

From the band’s side, Clarity marks an expanding and refining of everything they gestured towards on Static Prevails. There is a lot more space in the songwriting, but it’s also full of additional instruments – organs, synths, timpani – that add layers of fine detail. Opener ‘Table For Glasses’ is borderline orchestral; a patient instrumental with twinkling guitar lines, strings, and delicate percussion reminiscent of early Low, while Adkins’ vocals – snow driven in its purity, now – overlap and interlock. In being so anti-punk in sound, it’s one of the most punk statements Jimmy Eat World ever made.

The space that started to open up on Static Prevails is mastered and tamed on Clarity. The measured patience in the songwriting feels almost painful, the melodies acute in their simplicity. The title track marries ragged guitars with building momentum and a vocal performance that shifts imperceptibly between breathy and belting, full of angsty sustained notes that would become Adkins calling card. On the more experimental end, ‘Goodbye Sky Harbour’ is a 16 minute sprawl with lyrics lifted directly from John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany. And, on the other side of the spectrum, ‘Lucky Denver Mint’ sees them use the glacial mood of Midwest emo as kindling for a perfect power pop single.

The lyrics are about a big night out in Vegas, when Adkins and a friend drank and gambled their money away, though it doubles as an ode to youthful hubris at large (“You’re not bigger than this, not better / Why can’t you learn?”). Similarly ‘Table For Glasses’ was inspired by a performance art show Adkins saw, where a woman cleaned a flight of steps with the hem of her white dress, ran towards a table set with candles and glassware, and brushed the dirt from her dress into them – though it doubles as a eulogy for love and adolescence both (“It happened too fast to make sense of it, make it last”). The universal mantra-like quality of Adkins’ lyrics tend to belie the specificity of their influences, which is what makes Jimmy Eat World so compelling in general. No matter how pop the sensibilities, there’s always something strange below the surface.

Clarity is the album that saw Jimmy Eat World officially branded an “emo” band, and as the subculture began bubbling towards the mainstream it became a formative influence on everything “emo” to come. Still, Clarity failed to shift the dial on emo’s commercial potential. With the exception of a lucky break in ‘Lucky Denver Mint’, which ended up on the soundtrack for the rom-com Never Been Kissed and exposed the band to a mass market audience, Clarity performed below expectations. Also, the president and A&R who signed Jimmy Eat World had left Capitol. So, as predicted, they were dropped – which only made it sweeter that their follow-up album would be their breakthrough.

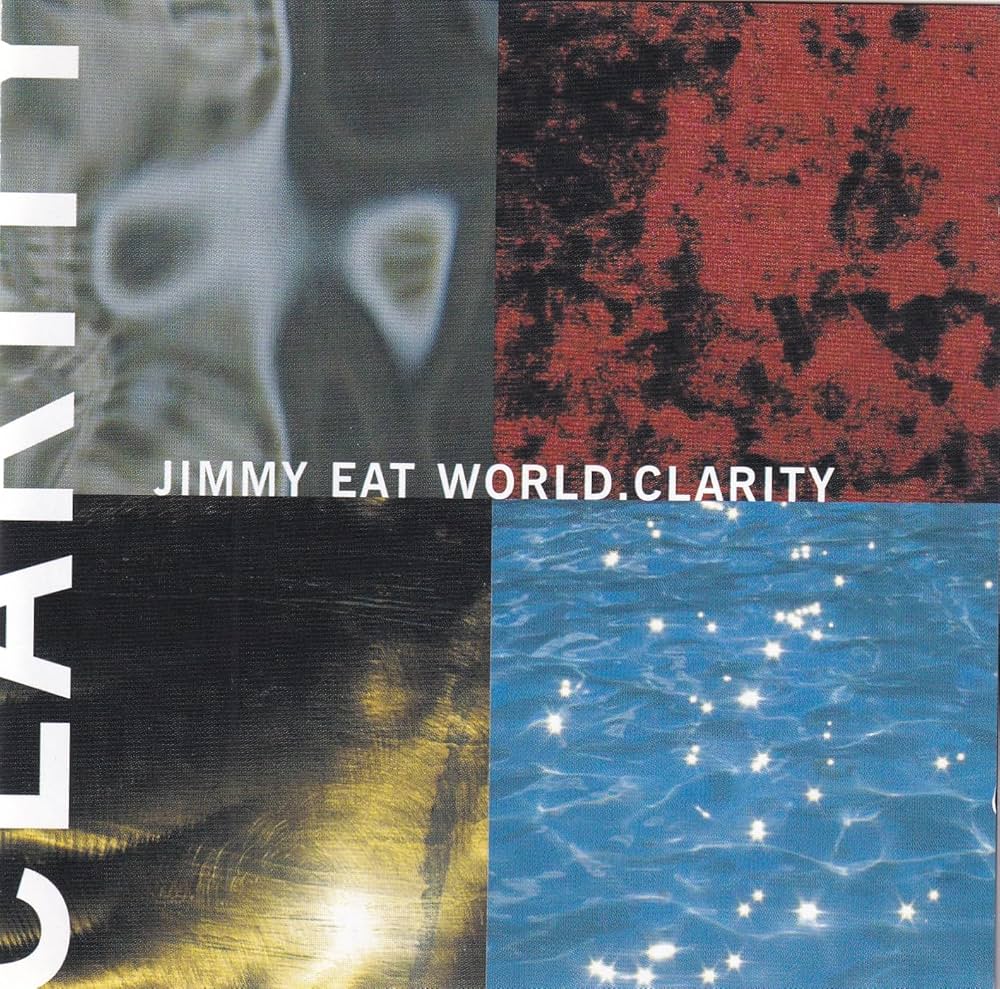

In 2001, emo hit the mainstream full pelt – aided, in part, by word of mouth spreading digitally through forums and early social media, as well as albums being passed around through p2p sharing. Released in March 2001, Dashboard Confessional’s The Places You Have Come To Fear The Most birthed the “sad boy” frontman stereotype and unlocked the potential for emo to be hawked to teenagers the way boy bands had been. In April, post-hardcore outfit Thursday released their second album Full Collapse, which broke the Billboard 200 and introduced a darker sound, with more direct roots in 80s emocore and a lyrical literary sensibility to match, into the mainstream. Then, in July, Jimmy Eat World released Bleed American and became the biggest so-called emo band on the planet to date.

Though the band was unsigned while they were writing Bleed American, Mark Trombino, who produced Static Prevails and Clarity, offered to work for free until they could repay him. He had faith the album would get picked up, but it wasn’t much of a gamble. Though Jimmy Eat World were dropped by Capitol, it was over misaligned expectations rather than a lack of growing interest. They were being tapped to play with bigger and bigger bands, booking larger venues with every tour. They had momentum behind them and a “clean slate” to work with, as drummer Zach Lind put it in an interview with The Ringer. Once completed, Bleed American received bids from nearly every major label besides Interscope. It went to DreamWorks’ musical division, and the title track was released as the lead single, capturing the bleak, insular mindset of post-Columbine American youth with its opening lyrics: “I’m not alone ’cause the TV’s on, yeah / I’m not crazy ’cause I take the right pills every day” – the moping 21st century answer to Nirvana’s nihilistic ‘Lithium’.

Full of frat house-friendly love songs, classic riffs, and stadium-sized choruses, Bleed American is almost like an emo heartland album. “We’d gotten interested in people like Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen – guys who wrote really great, big American rock songs,” Lind told Rock Sound at the time. Indeed, the chorus of their biggest hit, ‘The Middle’ was the result of Adkins asking himself: “What would Bruce Springsteen do?” More specifically: what would Bruce Springsteen say to the 14-year-old fan who wrote to Jimmy Eat World’s AOL account saying she was being shunned by the punks at her school for not being punk enough? He landed on “Everything, everything’ll be just fine / Everything, everything’ll be alright” – a sentiment intended to bolster a teenage girl’s confidence in the throes of puberty, that ended up becoming a generational clarion call for optimism when it was released as a single one month after 9/11. Taylor Swift, who would have been 12 when ‘The Middle’ was released, loved the song so much she went on to cover it live (occasionally with Jim Adkins), performing with the lyrics scrawled in marker on her arm.

After 9/11, Bleed American was re-released under the name Jimmy Eat World. The title track, too, was renamed ‘Salt Sweat Sugar’ to avoid inclusion on the Clear Channel memorandum – a list of songs considered inappropriate for airplay (which, incidentally, also included Bruce Springsteen’s ‘I’m On Fire’). The confusion around all this, rather than suppressing or obscuring the material, made its cathartic energy and introspective lyrics resonate all the more clearly. The discordant sound and overall feel-good messaging tapped into a state of anger and confusion that a generation of young people was suddenly plunged into, and its popularity reflected the need for an outlet.

There’s a solid argument to be made that the atmosphere of panic and uncertainty that set in after 9/11 is partly what made emo – with all its depression and hysteria – one of the biggest subcultures of the 2000s. While Jimmy Eat World were touring Bleed American, somewhere on the road between Cleveland and Minneapolis, a young Gerard Way witnessed the planes hit the towers from a commuter train into Manhattan, where he was interning at Cartoon Network. The experience affected him so deeply he returned to writing music as a way of processing it, thereby forming My Chemical Romance.

There is a duality to the songs on Bleed American that resonated far beyond emo’s usual parameters. A heavy cloud hangs over even the most fist-pump friendly singles – like ‘Sweetness’. The track explodes right out the gate with a call and response lyric that scans more like a cry for help from the void (“If you’re listening / Sing it back”). Adkins delivers the lines with urgency, vocal delay echoing his own desperation back at him, the whole song interspersed with “whoa oh ohs” that sound agonised in the verses and liberated in the chorus, where he’s “spinning free.” Ultimately the songs are laced with all the things that emo would come to be associated with in the 2000s and beyond: bleeding heart lyricism, angst-ridden instrumentals, and male sensitivity. Bleed American was certified platinum in 2002 and all four of its singles entered the Top 20 of at least one U.S. chart. Meanwhile, demand to see Jimmy Eat World live was so high they ended up touring the album for over two years, graduating from 400-cap clubs to selling out theatres seemingly overnight.

Between 1999 and 2001, everything changed. The decade changed and the dominant mood changed with it, switching from nihilism to earnestness. Jimmy Eat world changed, from a DIY band done good to a powerhouse name, with Bleed American ringing in a new subculture for a new youth in a new century in which nothing made sense. And emo changed, too – no longer a sprawling array of bands rooted in hardcore and doing their own thing with it in basements across the American suburbs, but fully fledged rock stars whose releases reflected generational sentiments and populated the global charts alongside Jennifer Lopez and Jay-Z.