There’s a line in Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York that dances on the wind in my head, where Hazel (Samantha Morton) hesitates as she considers buying a house that is perpetually on fire. She remarks to a placid real estate agent, “I’m just really concerned about dying in a fire,” to which the agent selling a burning home replies back with earnest resignation, “It’s a big decision – how one prefers to die.”

For a few years I lived above a haunted electrical supply store nestled behind the Ford dealership on Eighth Avenue in downtown Whitehorse. A two-bedroom apartment with a massive kitchen and dining room, outdated carpet, natural pine trim around the floor, and wallpaper acting as crown molding. It looked like the perfect memory of a 90s Chinese restaurant that never got renovated.

I lived up there alone, alone except Charlie, my gray tabby cat and the last relic of an old relationship who had followed me from apartment to apartment without judgment or questioning. Charlie, who had sat on the passenger seat of my midnight blue 2013 Toyota Tundra as we drove to Toronto and then again seven months later when I gave up and drove back to the Yukon.

This was my third apartment on Eighth Ave, and maybe there was something drawing me to the stretch of road the city never bothered to pave nestled in the shadow of a cliff that threatens to collapse and cover the homes that line its base. A big decision, how one prefers to die.

Late into the darkness of the night I would drink heavily, lie on the floor listening to records until they reached the end of their run and then just the rhythmic thump of the needle hitting the end of its journey. From the shop below, through the sound of the needle and drop of a bourbon bottle on carpeted floor, I could hear the faint sound of a handsaw cutting through wood long after everyone had gone home and turned off the lights of the shop. My landlord told me that the building had originally been a woodshed, and one night the guy who owned the place wrapped up the day, walked out into the woods, all desolate, dark, and cold in the winter dusk of the Yukon, and shot himself in the head. Now he was stuck here in this place, measuring twice and cutting once until time folds in on itself and all things end.

Ghosts never seemed to bother me; in fact I’m of the mind that most ghosts are relatively polite and the only way to ward them off is to signal that you’re busy: come back later, come back when I need to be shaken. Maybe ghosts just abide by their own kind and maybe that’s all I had become, the ghost of a life spent lying on the floor with a bottle of brown liquor listening to Springsteen records.

For years I had a perception of Springsteen that kept me in the weeds with his work. As a kid I had seen the cover to Born in the U.S.A. at my friend Tommy’s townhouse in the Sternwheeler Village across from the bowling alley. Springsteen seemed comically American, absurdly masculine. As a kid I formed a lot of opinions about all the things I was unable to comprehend because I thought that having opinions made you older, and if I could be old already in my youth then maybe I could get to the end early too.

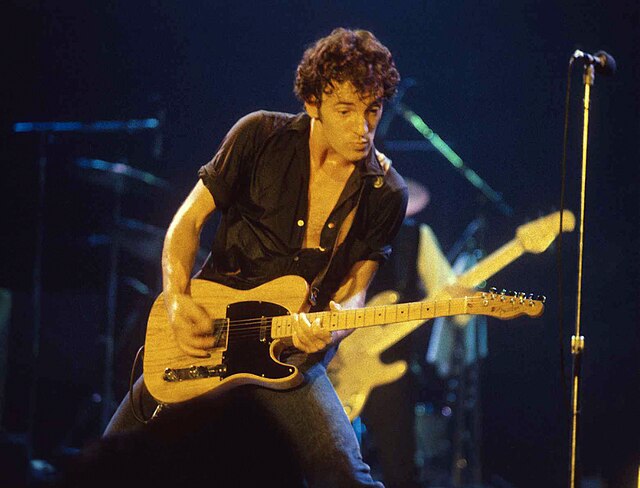

Born in the U.S.A. is the quintessential Springsteen record, with its iconic cover and oft-misunderstood ballad decrying capitalism and the American war machine. Born in the U.S.A. is the reference that anyone will easily draw when trivia comes calling for an answer, but this was in truth a moment of rebirth for the Boss. Born to Run, in 1975, had been the first big commercial success for him and the E Street Band, a desperate push to become a viable star after Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle had not provided enough raw ammunition to fire him into the limelight. Born to Run proved the songwriting and world-building potential of Springsteen, this man who could spin themes of the ennui of the exhausted working class, of the kind of desperate love that feels it may crush your tender heart into blackened coal, or into threads of pure silken gold.

Born to Run and follow-up The River (1978) cemented Springsteen as a statuesque titan of the possibility of rock music, tender and raw and rough all at once, the kind of man you could love so dearly you might lose all that you are. When you think of the music of dads and fathers, the mind conjures Springsteen before all others, because more than most he is the kind of man you wished had been the one that raised you.

Springsteen is the perfect idea of a man who is both comically masculine and as queer as a three-dollar bill. A voice like a wild animal backed into a corner that drips still with honey and lavender. There is a sweetness to his vision of the world, that all things are rough and the weight of the world a burden few shoulders can bear and yet there is love and yearning and desire amid all the hardships. Springsteen never promises that life and all things will be perfect, instead that there will be loss and heartache and you will love and you will lose but you will find the strength to go on.

By the time I moved into my apartment above the haunted electrical supply store on Eighth Avenue, I was tired from shuffling my body along a path going nowhere. I had folded my construction company, moved to Toronto, moved back from Toronto, took a job as a locksmith, hated working as a locksmith, hated myself for moving back from Toronto. Tired. Sad. Eyes sinking into the skull in preparation of closing for good.

I was always afraid, and fear will lead you into dark corners and sad places if you let it. Fear will hold you there until it has drained all that you are. I had tried to come out three times before, and each time it had been rebuked and I had internalized that this was a failure on my part. I had failed

to be strong, failed to be bold, failed to be who I thought I might be capable of becoming, and now I was getting old. By the time I moved into my apartment above the haunted electrical supply shop I was in my mid-thirties, and life had told me time and again that your mid-thirties are the point where anything you dreamed possible becomes just an opportunity you have already missed.

The day I moved into my apartment my bank account was frozen by the Canadian Revenue Agency. I had been accruing debt at an alarming rate over the last decade, and my taxes were too much to pay. I owed too much and had too little and so the bank froze my accounts, what money I had went

to the CRA, and I had to ask my mom for enough money to pay the first month’s rent, damage deposit, plus a box of mac and cheese while I waited for my situation to sort itself out. Debts no honest man could pay.

When I moved into the apartment above the electrical supply store, I knew almost immediately that I would become just another ghost haunting a house hidden at the base of a cliff. I knew I was going to die here. I had dreamed a thousand possible lives for myself in all the years before this one, and they had never once come true. I was so tired of dreaming and turning up nothing. I opened my construction company again, took on contracts and started to bring in some work, enough to make adequate money to start surviving again. I bought tools and food and a gun that I hid in my closet, and I thought a lot about death.

Maybe that was the real ghost of this place, the memory of the end. But I have always lived with intrusive thoughts and I have always dreamed of death, and for a long time I thought this was the place that dream would become real, the final dream I had left to realize after all others failed to come true. At night I lay on the floor, got drunk alone and cried, thought about my failed dreams, and listened to Springsteen records.

Born in the U.S.A. is about many things, but it is more than anything about defying expectations. Maybe that isn’t true, but drunk on the floor in an unrenovated 90s Chinese restaurant, it felt like an album that defied possibility.

As a kid I had believed Springsteen to be the patron saint of men I would cross the street to avoid interacting with, and maybe this is the deceptive wonder of the iconic Annie Leibovitz photo on the cover, Springsteen with his back turned, a red hat in the back pocket of his well-worn jeans, and the

red and off-white stripes of the American flag in front of him. In contrast to previous album covers, stark photos of his face on The River or him playfully leaning on his lifelong love, sax player Clarence Clemons, on Born to Run. This was the first time he was on the cover but still unseen, a man walking away, or perhaps toward something, but asking you to question why.

When he started working on the songs that would become Nebraska and Born in the U.S.A., Springsteen was in his early thirties. In his thirties and still desperately searching for something to define him, to bring him to that next and final stage, the quest for a big enough spotlight to feel seen in the heat of its brilliance. Nebraska became a brooding and pensive masterpiece, and Born in the U.S.A. a triumphant demand to be heard, to be loved, to be more than anyone believed him possible of creating.

In my thirties in my two-bedroom apartment, I slipped into the hardest moments of alcoholism. I took a part-time job as a bartender at the cocktail bar down the road. A building with two taxidermy moose on the roof, their horns locked in false battle. A fun bit of trivia that we would dole out to tourists taking endless photos of them was that the bodies were actually cows. Everything is a lie, posed and on display. My rallying cry as a bartender was that all shots were whiskey, shots I would eagerly down myself as others did, too, and when I wasn’t working I was drinking, and when I wasn’t at the bar I was at home, and when I was at home, I was drinking too.

Some nights, though. Some nights I wasn’t lying on the floor. Some nights something in me moved and shook and I would put records on and shuffle my feet around the house in an attempt at dancing. I would go out on my patio and smoke weed and cigarettes and drink and stare into the sky looking for nothing and think for just a moment that maybe this is just what life was. Sad and dark but there was time to dance still. Some nights I thought about the gun hiding in my closet. A big decision, how one prefers to die. Some nights I would just breathe out, deeply, and watch my breath turn to smoke in the air and think about nothing for a second. Some nights I was free. Some nights I was alone and when I was alone I could be anyone for seconds that threatened to become hours.

I wasn’t treating anyone terribly well, least of all myself. Distant to most or putting on airs of overconfidence and determined heterosexual masculinity. I owned a construction company, I owned a truck, I had scars from years of injuries, I had sore muscles and a bad back. In the winter the year after I moved into that apartment I slipped on the ice at the dump and impacted my tailbone, forcing it up and to the left, where it moved into the space occupied by my hip bone. Some days it became too painful to stand up. Painkillers. Booze. Darkness.

Some nights Springsteen records were the only thing saving me. My failing relationships, the piles of debt, the going nowhere of it all. In August 2017 I took the gun out of my closet and sat with it on the bed, and wondered what would happen afterward, when this was all over. What happens after

we die. I thought about all my friends and family and former lovers that had died and would I see them somewhere beyond all this? Would they remember me? Would they want to see me? Would I be like this, in this body? Could I be remade? Springsteen playing in the living room on the record player.

Want to change my clothes, my hair, my face.

That line in ‘Dancing in the Dark’ followed me from room to room. Springsteen didn’t even want that song on this record. Did you know that? Little facts trading hands. Springsteen had fought so hard to make this goddamn record. Legend has it he wrote fifty to one hundred songs around the period of Nebraska and Born in the U.S.A., and the producer goaded him for one more hit and he just kind of lost it. In Glory Days, Dave Marsh writes that Springsteen was pissed off at the urging to write one more solid hit. “I’ve written seventy songs. You want another one, you write it,” Springsteen said, stormed out, walked back in, and wrote one of the greatest songs of his career. He was just mad enough to make something beautiful. ‘Dancing in the Dark’ is a snapshot of loneliness and isolation. How we rebuild ourselves in these moments. Springsteen was in his thirties now, and struggling to continue to be the kind of man that he had been all the years prior to this one. The River had been a great success, and Springsteen was starting to feel isolated by the success, by the pressure of expectation and the performance of Bruce Springsteen over the reality of the man.

Radio’s on and I’m moving ’round my place.

If you don’t believe your life can change on a dance floor, I believe you are lying to yourself. Halloween of 2017 my then partner and I were going to different parties, and in a last-minute quest for a costume to hide my body and my alcohol I dressed in a shark costume, put a blazer over top, and filled my pockets with fake money: loan shark. I drank a half-bottle of cheap scotch at home, filled a flask with whiskey and a plastic bag with cans of cheap Pilsner, and went to

a party.

That night I danced and snuck booze under my costume, did shots in the kitchen, did drugs in the garage. I went to the bathroom and swayed in the mirror trying to find my reflection and mouthed the words “fuck you” to the face staring back through me from the mirror. The DJ played the hits, I danced a little but could never find the rhythm, and then someone played ‘Dancing in the Dark’ and I felt an overwhelming sense of bitter sadness, as if I had been struck by a lightning bolt of depression. I snuck out, walked home in the winter wearing a shark costume for warmth, drank bourbon and whiskey and told my partner to leave me alone, and fell asleep on the floor with the rhythmic thump of a needle hitting the end of its run.

For days I drank alone, went to work for a few hours, came home, drank. Floor. Drink. Floor. Floor. End of the loop. The rhythmic thump of the turntable, the ghost downstairs, and the end of life. I thought about all the times I had tried to come out and been rejected. I thought about the life I thought I could never have and how all of my time was gone. My intrusive thoughts. I thought about death. Death. Death. Death.

I sat on the bed with a gun and thought about what happens next, and somehow in all of this I decided instead to drive myself half-drunk to the hospital and told the admissions nurse I was in pain, could someone see me. My doctor happened to be the one on call, and through it all I think he

could see me, too, and he told me he would keep me there for a few hours for observation.

I went home. I bought a double Quarter Pounder meal with a large fries and six-piece McNuggets, lay in the bathtub with them and a bottle of bourbon, played Springsteen on the stereo loud enough so the words could reach me no matter how far I ran from the truth, and stayed there until the water ran lukewarm, then cold. Charlie came in searching for fries, his special treat. I remembered how every time I came out to someone they rejected me, and so I texted my partner and asked her to come over so we could talk, and I planned to tell her my truth, the truth that had pushed so many away, and then like a coward I could be free and then I could die and all this would be over.

Want to change my clothes, my hair, my face.

She came over, and I stared into my feet and told her I had dysphoria. Gender problems, you know. I don’t want to be this anymore. I prepared myself for the pain, knew it; it had been so long I almost craved how it felt. Like getting a tattoo after an absence of fresh ink. I never expected her to say what she did, but bless her for doing so.

“Okay, so what do you need that will help?”

The Dad Rock That Made Me A Woman by Niko Stratis is published by the University of Texas Press