At its deepest, an elegy is a mourning not just for an individual, but a place and time now lost forever. You can hear this in everything from Charles Mingus’ jazz requiem ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ for the late Lester ‘Pres’ Young to Gavin Bryars’ homeless choral ‘Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ to Scott Walker’s threnody for Pasolini, ‘Farmer In The City’. These are memorials but they are also boundary markers, across which there is no returning.

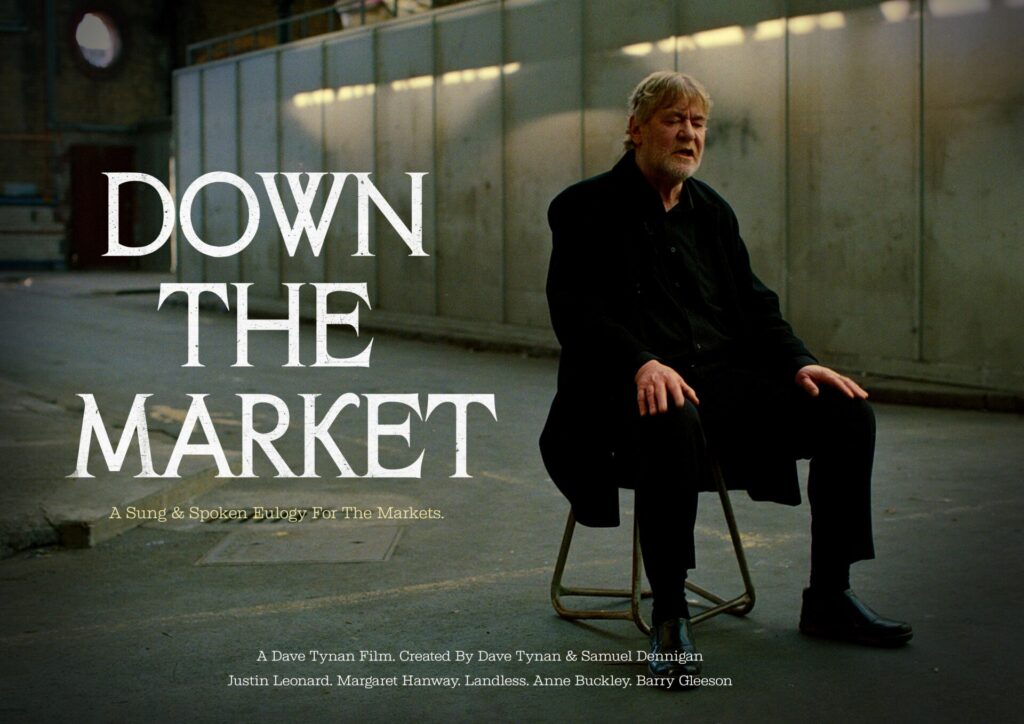

We are currently living through the greatest period of urbanisation ever seen in history. And the creative forces it has unleashed are matched by the destructive. The heart and soul of cities, the cultural ecosystems and rain cycles, the basic ability to survive, are all under threat. Dublin is no exception. Created by Dave Tynan and Sam Dennigan, Down The Market focuses on one of the fallen – the closure of the Smithfield Market, which had existed on the Northside since 1892. It’s a cinematic elegy and a musical one. Irish folk music is rife with elegies, chiefly because, after 800 years of the tender mercies of its neighbour, Irish history is rife with dead bodies, gutted buildings and extinguished greatness. To listen to ‘The Lament For Owen Rowe O’Neill’, ‘Tuireamh Mhic Fhinín Duibh’ or ‘The Foggy Dew’ or a thousand other melodies is to hear different eras pass seemingly into oblivion. What you hear though is not simply absence but the survival of something profound, in terms of memory, identity and spirit, that transcends the simplifications of words. You can hear it in Landless’ a cappella keening of ‘Caoin’ in Down The Market. They return with ‘Unst Boat Song’ sung in the Norn language and reputedly Shetland’s oldest surviving tune. There are reminiscences from former traders at the markets, Justin Leonard and Margaret Hanway, while Barry Gleeson and Anne Buckley capture the lively, and lamenting, Dublin street-folk tradition (with Billy Treacy’s ‘The Market’ and Pete St. John’s ‘The Inchicore Wake’ respectively).

Every elegy is a lamentation, a celebration and, crucially, a protest. Down the Market marks the loss of markets but also a vernacular of space and speech, a circulatory system of trade and produce (local and exotica), a place full of characters and generations. Time will tell if it can retain its soul, or any soul, in the face of so much sterile corporate development, which could be anywhere and thus feels like nowhere. Its epitaph in the film is fittingly a dedication, given it is people who make a place, “For all those who passed by Halston Street and shared a laugh. For the rows and the deals. For the late early morning starts and the struggle on the cobbles. Forklifts lifting breakfast rolls. Mind your fingers. Glued keyholes. Beached whales. Pepper traps. Piper frying white and no ice no slice. Good luck and see you in the morning.”

I spoke to Dave Tynan – the director of Down The Market and author of the ‘portrait of Dublin and Dubliners in flux’ We Used To Dance Here published by Granta – earlier in the year.

What drew you to the market and the theme of absence?

Dave Tynan: I’ve always loved the building. It must have been one of the biggest indoor public spaces in the city. I’ve always lived within walking distance of it in Dublin. It closed in 2019 and probably lockdown exacerbated things for me. All of town was absence; cities are strange places without people. I’d been wanting to work on something about traditional singing too. That was the nub of it: to let singers sing, in full, in one take, to honour the singing, by not cutting and then to develop that, so that we find these singers in this empty space that was so full of life before. It’s an attempt to match the integrity of the songs, in cinema. A held shot is a tiny act of resistance, an argument in another direction or a path rarely taken. The hope is it demands attention but rewards that attention and that’s a richer experience.

There’s something incredibly haunting and atmospheric about the acoustics and emptiness of the place in the film. Tell us about the voices you chose to fill it.

DT: The Bleaching Bones EP was the first I heard of Landless, though they’ve been together long before I heard of them. They’ve an incredible sound, so stark and so human. I thought they’d nicely establish that sense of absence, nearly a spectral quality. Barry Gleeson just has one of those voices. I approached him about singing a different song, but he rightly shut that down and suggested ‘The Market’. It was one of those lovely times where somebody improves your idea way beyond what you’d conceived. Barry’s retired now but he was a teacher and ‘The Market’ was written by a student of his, Billy Treacy, who grew right beside the markets. I loved that. It couldn’t be a better fit, like it fell out of sky for us.

With ‘The Inchicore Wake’, the song led me to the singer. It was written by Pete St John, and I loved the elegiac tone of it and then there’s the words: Bigamy O’Keefe was a real person apparently. Christy Moore has sung the song recently, and he said that Pete St John told him Bigamy was married six times. Ian Lynch suggested Anne Buckley to me as she already sang it. I didn’t know Anne, but she’s a regular singer in the Cobblestone. She knew so much about the song. One nugget I remember is that Mushatt’s Balm is mentioned in the song, which was sold in Jewish chemists, but apparently it was a euphemism for contraception at the time. With the traders, a friend and the co-creator of the film, Sam Dennigan, had worked around the markets and knew some of the traders. He introduced me to Justin and Margaret.

Folk music features throughout Down The Market. There seem to be parallels there with the theme of the film – vernacular culture under threat from capital and philistinism, sometimes succumbing but sometimes being revitalized by the vigor required to survive. Irish folk music seems to be thriving these days. For a form that goes back so far, it feels exciting, inventive, edgy, capable of conveying and resisting the shitshow of the 21st century, and being the custodian of otherwise lost precious things. Why do you think that’s happened?

DT: I’m wary of speaking on behalf of a scene I’m not part, or calling it a scene. I’m just a fan and I’m wary of scenes in general. But traditional music seems in a healthy place now. Maybe that’s people looking for something that feels local or has a sense of place. The world is globalised now and it’s also a burning world, so maybe it gives people some ownership. I’m very proud of how Dublin this film is.

I guess traditional music has a different presentation to a lot of popular culture, in contrast to a lot of entertainment but I think that’s also of great value to people. It doesn’t go pleading for clicks or likes but it’s deeply human, it’s storytelling and it’s deeply aware of people and place.

It’s worth saying that people kept the tradition going and that’s worth a lot, maybe especially when there was less of a spotlight on it.

DT: I won’t pretend to know them, but places like the Cobblestone or the nights like the Góilín, there’s so many singing sessions around. For whatever reason, back-to-back recessions maybe, a reaction to a globalised world, I don’t know, there might be more people making – and receptive to – creative work that’s comfortable with itself, that owns itself. I want to say too that Barry’s album Path Across The Ocean from 1994 deserves to be known much more than it is. I wish someone would press it on vinyl.

The atmosphere of the market is something else. You can close your eyes, during the songs, and hear the space. Were you aware of the light and sonic qualities of the setting before filming?

DT: I knew the acoustics were there, just that in a space of that size unaccompanied voices would give us something really special. Credit to Chris Carroll and Mark Henry who did the sound recording and mix respectively. We haven’t had an amazing festival run, which hurt my feelings and my wallet. If you can’t try things in film within the short form, where can you? Any time I’ve seen it in a cinema, it’s a real experience. That’s just to say, if you’re watching at home, full screen and sound up!

You can’t really control the light in a space that big but the sun played ball and came out during Barry’s takes, which was nice. Shout out to cinematographer Keith Pendred, it was a great collaboration. I’m sure he’d have liked a Steadicam, but I think he did a wonderful job. It was a lot of long takes, sometimes in stress positions, all shot in one day within daylight hours: hero work. I think a director’s job is to help a performer make magic between ‘action’ and ‘cut’ but something like this, where I wanted to explore the space at the same time as the singer develops the song, I can only go there with a cinematographer.

The urban environment in Ireland (like Britain) is a shambles – the housing crisis, gentrification, the destruction of heritage, the erosion of working-class culture. It’s always posited as some inevitable deterioration with managed decline the only option but it’s clearly entirely preventable and immensely profitable for the few. Down The Market is a moving piece but also there’s an implicit rage hidden in there too. How do we begin to face what’s happening before it’s too late?

You’d have to start with the amount of vacant homes in the country. The statistics are shocking. There’s more than 48,000 homes vacant for more than six years. People living in tents is a real part of the urban environment in the city centre. I love town. I grew up in town but the most interesting and vital part of the city seems the most ignored. When a city is so aggressively unaffordable, the loss is incalculable, not just in terms of its culture, but in every facet of how a city and its people live.

The market itself is still closed. There have been a lot of plans mooted, but I don’t think anything’s about to happen any time soon. There’s great – and terrible – examples out there of what can be done in terms of making it a new public space. Having it sit empty is a terrible thing.