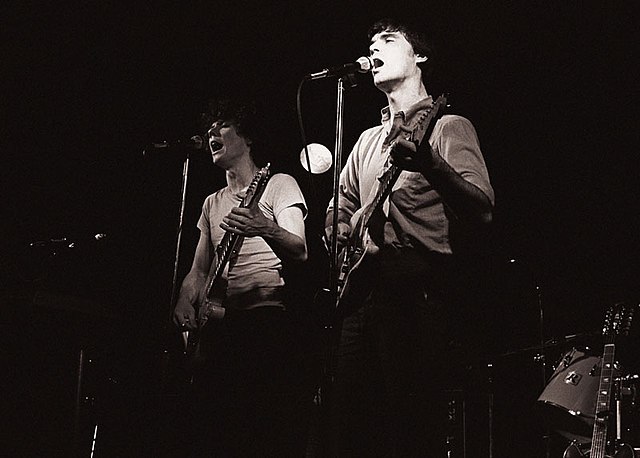

If Talking Heads have a magnum opus, it is surely 1980’s Remain in Light. More than a mere maturation in the band’s sound, the album marks the culmination of frontman David Byrne’s intellectual tête-à-tête with producer Brian Eno. The two met in London in May 1977 while the Heads were on tour with the Ramones. Eno’s avant-garde credentials gave gravitas to the scrappy Heads, who were still ambling on stage at CBGBs and had yet to release their debut album. He became an unwitting Pygmalion to the bookish Byrne: on sojourns to California and the Caribbean, they discoursed at length on cybernetics and Afrobeat.

The benefits brought by the Eno collaboration were felt by other band members, too. His Cageian tendency toward happenstance in the studio gave agency to bassist Tina Weymouth, keyboardist Jerry Harrison, and drummer Chris Frantz, who had each been frustrated by Byrne’s need to exercise control and treat them like also-rans.

Yet Eno’s pretensions ultimately alienated the Heads’ rhythm section, spurring them to establish the sanguine side-project Tom Tom Club. Weymouth, always Byrne’s foil in interviews, had few kind words to say about Eno’s artist statement for Remain in Light. “This is bullshit, Eno,” she declaimed. “You should just do interviews with Artforum and forget the pop world.”

Many tensions drive Jonathan Gould’s new book Burning Down the House: Talking Heads and the New York Scene that Transformed Rock, but perhaps none more so than the tension between art and pop, between innovation and convention. The great irony in Weymouth’s quip about the art world’s most august publication lies in the fact that she – and Frantz, her eventual husband – were the only members of the Heads who actually graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (the “Harvard of art schools,” as Frantz told his parents). Byrne had aimlessly spent his freshman year fucking around with a Xerox machine and devising questionnaires about UFOs under the auspices of Conceptual art, dropping out after two semesters. He transferred to the Maryland Institute College of Art only to return a year later to Providence, hoping to re-enroll at RISD. His petition to the faculty was ultimately denied – but like Thomas Hardy’s Jude, he rented an apartment and remained nearby, socialising on the periphery of the school that became his lost Atlantis.

My invocation of Atlantis runs the risk of mythologising Byrne and his band. But Gould’s book is gently attuned to the various ways that Byrne has tended to his own image. Since he first took the stage at CBGBs with Weymouth and Frantz in 1975, two characterisations have followed Byrne in the music press: one, that he is a hyper-literate former art school student intent on injecting intellectualism into the lifeblood of pop music; and two, that he is a discomfiting social misfit whose habitus eerily recalls Anthony Perkins in Psycho. Little of what Gould writes contradicts these two descriptions. Instead, what he deftly does is demonstrate how the combination of these qualities allowed Byrne – to borrow from the book’s title – to “transform rock.”

But what of the scene named in said title? What, even, of the other Heads? As Gould notes, Weymouth often bristled when profiles of the band hit newsstands as single character studies. Yet Burning Down the House largely hews to this form. Though they are each given full introductory chapters, Weymouth and Frantz primarily function as sharpshooting “straight men” to the mercurial Byrne. New York’s presence is similarly spectral. It flickers in and out of the narrative – in gloomy scenes on the Bowery, at raucous dance nights at the Mudd Club, and through nods to the urban infrastructure that both enabled and inhibited the art scene. Gould is quick to remind us that the collapse of Robert Moses’s LOMEX dream in the early 1970s allowed artists to move en masse into downtown buildings previously at risk of being demolished. But he also acknowledges the perils faced by artists who attempted to scale great heights. Sometimes these heights were literal: acrobat Philippe Petit was arrested by the Port Authority in 1974 after he dared to tightrope walk between the World Trade Center’s newly erected twin towers.

Like the works of Sol LeWitt that so delighted Byrne, the city serves as the book’s conceptual framework, more than its setting. Gould’s first chapter opens with an epigraph drawn from E.B. White’s Here Is New York. “The residents of Manhattan are to a large extent strangers who have pulled up stakes somewhere and come to town,” White writes, “seeking sanctuary or fulfillment or some greater or lesser grail.” Manhattan, in Gould’s study, becomes a metaphor for Talking Heads – or, more specifically, for Byrne’s relationship to his bandmates. When Frantz and Weymouth moved to Queens early on in the band’s career, they created a social fracture, transforming the relationship between bandmates into that of strangers engaged in the same pursuit. Frantz and Weymouth soon settled into a life of personal and professional contentment. After they left New York for a sleepy commuter town in Connecticut, they playfully described themselves as “Mr. And Mrs. Average Suburban Couple.”

Byrne, by contrast, never became content – nor did he ever leave New York. More than his bandmates, he embodies the striver ethos that Gould, by way of White, ascribes to the band. Frantz and Weymouth made the choice to pivot to pop music after graduating from RISD because they accepted that they couldn’t “cut it” as painters. But Byrne had this choice thrust upon him by the RISD faculty who deigned not to re-admit him. Imposter syndrome shades his early encounters with such art-world luminaries as Robert Wilson, Philip Glass, Twyla Tharp, and the aforementioned Eno. An argument could certainly be made that he cozied up to these figures seeking the validation he was denied by his professors.

But that would be too simple a reading of Byrne. Gould speculates, with understated sympathy, that Byrne’s autism – self-diagnosed in middle age – had much to do with these alignments. “I figured, I’ll make friends with a socially adept person and they’ll be the one who brings everyone in,” Byrne is quoted as saying. “It sounds very calculated, but it wasn’t quite as much.” He was also simply smart about what it takes to be a good artist. He recognized that good artists become great by being in community with others – the very purpose of going to art school. Though The Catherine Wheel, Byrne’s collaboration with Tharp, his one-time lover, failed to scale the heights it intended to reach, he did learn from the choreographer the importance of movement. Hours of rehearsal footage for the tour that would give us Jonathan Demme’s concert-film Stop Making Sense show Byrne carefully refining the jerky, almost inhuman gestures that characterized his early stage dancing.

Byrne’s tightrope walk between art and pop wasn’t always an easy one. His few forays into the fine art world during the 80s were not appreciated by art critics intent on maintaining the boundaries of their discipline. The P.S.1 group show New Wave/New York, a maximalist hodgepodge of artists whom curator Diego Cortez heralded as the scene’s tastemakers, was dismissed by Richard Flood in Artforum for its celebration of celebrity, its vacuous cool. But one gets the sense that Byrne himself might not have cared. His performance on the ironically titled song ‘Artists Only’ takes jabs at the hallowed medium, painting, that gallerists hellbent on commerce had returned to after a decade upholding Conceptualism. Taunting the listener, he squeals “I’m painting again!” though he doesn’t quite seem happy about it. An atmosphere of anxiety sets in before he triumphantly declares, “all my pictures confused,” rebuking the authorities to whom he previously felt he had to prove his creativity.

On ‘Artists Only’, as on nearly every early Talking Heads song, Byrne is tense and nervous. His inability to relax, Gould implies, is precisely what made the Heads such a singular force within punk and new wave. He was always striving, always anticipating. As James Wolcott wrote in his 1975 piece ‘The Conservative Impulse of the New Rock Underground’ for The Village Voice, much of the punk movement was driven by a desire to recover the raw energy of original rock and roll, before it had been bastardised to the point of parody by prog rock and other mid-70s genres. Patti Smith was a self-described “hero worshipper,” a sometime music critic who wrote loving screeds to The Beach Boys and other bands of decades past. Frantz and Weymouth might have fit into this camp, but Byrne assuredly did not. As an adolescent, he cut his teeth teaching himself guitar via Kinks covers and Beatles melodies. But other preoccupations proved more prescient. The child of an aerospace engineer, he was obsessed with UFOs – with what lies beyond in the great unknowable.

I came to Burning Down the House as I imagine many readers will: fascinated by Byrne, but more similar in sensibility to Frantz and Weymouth. I am at heart a Pollyanna-ish American Midwesterner, indestructibly sentimental. When I picked up the book, I expected to find a rose-tinged paean to a lost moment in New York cultural history – my personal Atlantis. The opening White quote and subsequent nods to Lucy Sante certainly tease us with nostalgia. But each time I closed the book while reading, I remembered its title. Having few sentimental attachments to both the art world and the history of pop music, Byrne was free to innovate, to rewrite the rules of what it meant to be a rock star. Byrne, baby, Byrne.

Burning Down the House: Talking Heads and the New York Scene That Transformed Rock by Jonathan Gould is published by Mariner Books