The international news headlines were pretty grim in 1975. Lest we forget or never knew in the first place, events that year included the Angolan civil war, a flood in China that led to the deaths of 230,000 people, an Australian submarine leaking nuclear waste, a bomb at LaGuardia Airport in New York, a German embassy siege in Stockholm by the Baader-Meinhof gang and two assassination attempts on President Gerald Ford.

If you were a kid in the 70s, as I was, not much of that filtered down, but we were still bombarded with terrifying public safety adverts on TV that made drownings, electrocutions, abductions and stepping on shards of broken glass seem commonplace. These came from the UK government’s Central Office Of Information, whose name somehow managed to hint at both Franz Kafka and George Orwell.

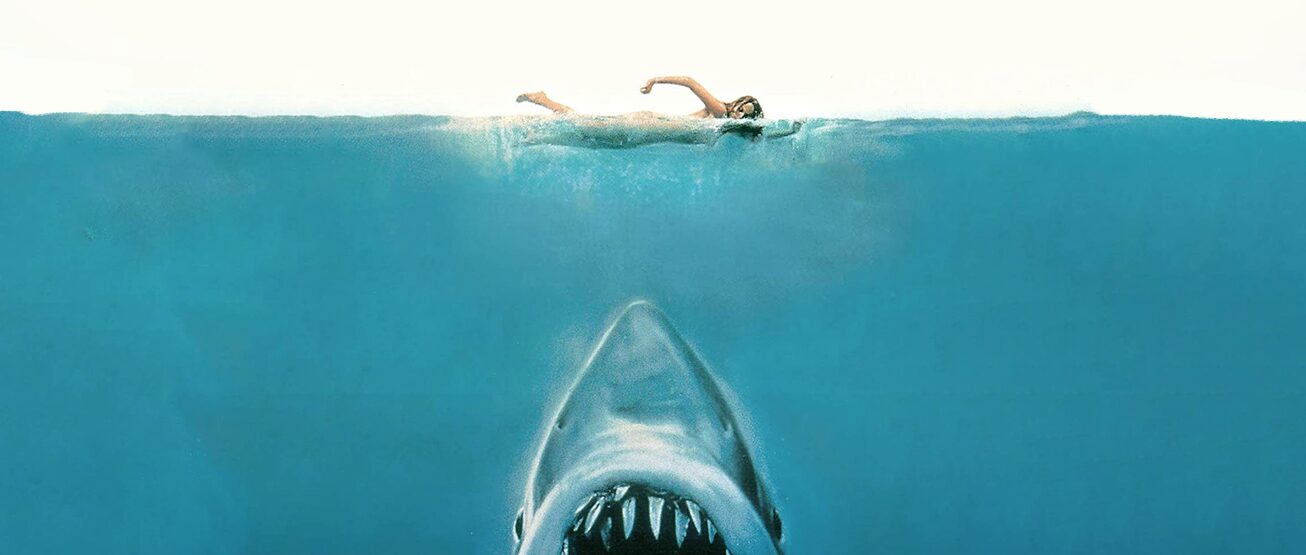

You might think that people would have preferred to watch cheerful stuff at the cinema in the mid-70s – and indeed, Shampoo, The Return Of The Pink Panther, A Star Is Born and the first Star Wars film all played well at the box office – but regardless, the biggest cinematic hit of 1975 was Jaws, an absolutely merciless two hours of tension and bloodletting.

I suspect you know the plot already, but essentially it’s about a great white shark that terrorises the fictional beaches of Amity Island, chewing up tourists and locals alike to the dismay of police chief Martin Brody and Mayor Larry Vaughn, albeit for different reasons. Brody wants the beaches closed to save lives, Vaughn wants them to stay open to make money. Eventually a veteran fisherman, Quint, is recruited to kill the shark and, joined by Brody and ichthyologist Matt Hooper, the chase is on.

My exposure to Jaws came early – too early. Around 1981, when I was about 10, I was left in a room with some other kids at a house we were visiting. My mum and dad were elsewhere in the house, merrily drinking wine with the other adults, so there was no-one to stop us when one of the other pre-teens picked up a random video cassette and put it into the VHS player.

As we watched, I got more and more anxious. The swimmer being attacked in the opening scene wasn’t particularly graphic, although the shots of her being yanked around the sea surface by an unseen force were unnerving. Half an hour later, though, I experienced a moment of real terror. I clearly remember the sensation of fear, almost like being physically cold, that enveloped me when the infamous severed head – with one eyeball missing, replaced by repulsive strings of gristle – popped suddenly into view.

Perhaps naively, I always assumed that this jump-scare – one of the most famous of that period alongside Regan’s pea-soup vomit (The Exorcist, 1973), the undead hand (Carrie, 1976) and “Kane’s son” (Alien, 1979) – would terrify anyone, but I was wrong. A few years ago, when my son was about the same age, he asked to see Jaws, and although I was a bit worried about it for obvious reasons, I sat with him and we watched a few parts. I didn’t want to show him Quint getting bitten in half, or to make him sit through the death of doomed pre-teen, Alex Kintner – especially not in this graphically enhanced 4K iteration – but I did think he could handle the rubber-head bit by that stage. When the moment came, I warned him that something grisly was about to happen, but when the head appeared he literally laughed out loud at how crap it looked, told me Jaws was boring and asked if we could watch something else instead.

This blew my mind, given my own reaction of utter terror to the monocular head at the same age, although I do accept that the special effect looks a bit cheap nowadays. Afterwards, I kept thinking about the differences between his and my reactions to that scene. In my case, I watched Jaws young and unsupervised, which might explain why it still exercises such a grisly fascination over me now. Even aged ten, I knew I’d get told off if we were discovered watching Jaws, so obviously the film has that forbidden, exciting allure.

But my generation liked Jaws for many other reasons that don’t apply to Generation Z. Horror was new, or new-ish, in the mid-70s, and that newness gave it added lustre. There was a lot of it about, even on TV. Quite aside from Jaws being the biggest-grossing film of 1975 – and after that, until the first Star Wars came along in 1977 – there was Trilogy Of Terror, a three-part American miniseries whose first two parts weren’t particularly scary. The third part, though, was mind-numbingly terrifying to the unsuspecting kids who watched it when it was broadcast at 8.30pm – prime time! – on 4 March that year. It’s still pretty upsetting today, so think twice before you click here.

This feeling of transgressive newness emanates from the pioneering Jaws, especially if you bracket it into the slasher-film category, which you can reasonably do even though the villain has teeth rather than a knife, axe or chainsaw. Psycho had established the stalk-and-stab format back in 1960, and the concept had got significantly nastier since then with films such as The Last House On The Left (1972) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). The first blockbuster of the genre is generally thought to be Halloween (1978), one of the most profitable films in cinema history, but there’s a strong argument to be made that Jaws laid much of the groundwork for that movie.

This is partly because Jaws was so well made, with a decent budget of $9 million (over $50m today) from Universal Pictures. Released on 20 June 1975, it was adapted from Peter Benchley’s airport novel from the previous year by a hotshot young director, Steven Spielberg, who had the necessary vision and ability to shoot it convincingly, assisted by a top-drawer cast that included Roy Scheider (Brody), Richard Dreyfuss (Hooper) and a super-oily Murray Hamilton (Vaughn). As everyone knows, not just Jaws fans, John Williams’ heart-palpitating score is as much a part of the horror as the on-screen visuals.

The most enduring character is easily Robert Shaw’s marvellous Captain Quint, an Ahab whose hatred of his enemy derived from a brutal encounter after the torpedoing of the USS Indianapolis during World War II and who takes Brody and Hooper along with him to the point of death, a particularly horrible one in his case. Spielberg made it into an appalling, dragged-out sequence – with no accompanying music, to emphasise the terror – in which Shaw screams his lungs out as his worst fear materialises. The moment when the shark crunches down on his torso and he gobs up a load of technicolour blood is still shocking.

Fortuitously, Jaws was also made at a point in special-effects technology where you could build a larger than life mechanical shark but not actually have it appear on screen for more than a few seconds because it looked so unconvincing. In addition, the fake sharks didn’t work when exposed to seawater and kept breaking down. Three of them were built, all nicknamed Bruce after Spielberg’s lawyer, but even after $3m of budget, the “special defects department” – as the director furiously labelled them – gave up.

This meant that Spielberg had to reduce the shark’s appearances on screen, using Williams’ ominous score to suggest its presence and shooting from the water level upwards, an unexpectedly effective technique. Hence Bruce the shark’s screen time of only four minutes across the 124-minute film, a less-is-more approach also adopted by necessity in Alien four years later. Those four minutes are horrifying: any longer would have diminished their impact.

The other point in favour of Jaws inspiring Halloween is that the antagonists are uncannily similar in some respects. Spielberg has since called Jurassic Park “Jaws on land”, and in fact, in 1976, the low budget man versus bear shocker Grizzly was marketed with the same tagline, but arguably the idea can most faithfully be applied to Halloween. Both films were harrowing because they presented the convincing idea of powerlessness against an unstoppable, amoral stalker. This was also echoed in Alien – itself a kind of ‘Jaws in space’. All three antagonists – Bruce, the Xenomorph, Michael Myers – have similar character traits: you mostly don’t see them because they’re hiding in the dark; they attack suddenly and viciously; and none of them have recognisable faces. More specifically, the villains’ eyes are highlighted as absences, with the shark in Jaws having notably dead orbs. (Quint says: “He’s got black eyes, lifeless eyes, like a doll’s eyes. When he comes at you, he doesn’t seem to be living – until he bites you, and then those black eyes roll over white.”) It isn’t clear if the Xenomorph has eyes at all or how it tracks its prey, and as for Myers, his face is mostly obscured with a mask that creates socket-like voids.

The inhuman-villain idea was borrowed and taken to its logical limit by 1984’s The Terminator, whose titular cyborg is just as unstoppable as Jaws’ great white. Its pitilessness is summed up memorably: “It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity or remorse or fear, and it absolutely will not stop – ever – until you are dead.”

On that note, compare the very similar description of Halloween’s Myers: “I met this six-year-old child with the blank, pale, emotionless face – and the blackest eyes – the devil’s eyes… what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply – evil”, and “There was nothing left – no reason, no conscience, no understanding, even of the most rudimentary life or death, good or evil, right or wrong.” Give Myers teeth, fins and a tail and you’d never know the difference.

The inhumanity of these monsters is the whole point. We are diminished and rendered lesser when we are faced with an adversary other than ourselves. As the writer Dawn Keetley puts it: “Jaws made it clear, before the slasher subgenre really got going, that what was at the heart of the slasher was this nonhuman force – and sometimes it looked human.”

Audiences flocked to see this horrifically implacable beast wreaking carnage on-screen, and the commercial performance of Jaws meant that critics had to take it seriously – and that rival studios were keen to make a horror film of their own. Unlike previous cult horrors, Jaws made $100 million in its first two months on release and has gone on to make over $2 billion (adjusted for inflation) despite the limp 1978 sequel and two even worse instalments that followed in 1983 and 1987.

The timing and placement of the release of Jaws was also innovative. The critic Mark Kermode wrote in 2015 that part of the film’s commercial success was due to its release in American shopping-mall cinemas, where increasing numbers of kids hung out during summer in the mid-70s. He cites the film historian Thomas Schatz, who pinpoints a new audience of film consumers who had “time and spending money and a penchant for wandering suburban shopping malls and for repeated viewings of their favourite films”.

The fact that such cinemas were air-conditioned in summer was a useful bonus, and the $2.5m marketing budget that accompanied Jaws – a novel idea at the time – also paid off handsomely. Thus the concept of the heavily-promoted summer blockbuster was formed at a time when Christmas films were traditionally the most lucrative releases, an economic switch confirmed a couple of years later when the Star Wars films were released to cinemas during the summer.

Above the enduring appeal of this particular shark, and its economic impact, what else does the film stand for? According to many an enthusiastic academic paper on that very subject, it’s an homage to Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick; and it’s also been frequently suggested that Jaws is a reference to the Watergate scandal that led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974, given the illegal and immoral attempts by the Mayor Larry Vaughn to hide the shark’s predations.

There’s also a popular theory that Jaws reflects the ongoing Vietnam War, whose graphic violence entered people’s homes via nightly TV reports and the accounts of returning soldiers. Reinforcing this idea, 1975 was the 30th anniversary of the end of World War II, in which a popular portrayal of America’s involvement was as saviours of the world: it’s thought that Quint’s WW2 speech was an attempt to recast the ongoing Vietnamese conflict in that comforting light.

With those points duly noted, a different allegory exists in Peter Benchley’s original novel, a somewhat deeper work than the film. Although it barely makes it to the screen in the film, the book addresses Brody’s fears about losing his family, a father who can’t protect his kids in the face of an implacable enemy. He’s also a cuckolded husband without knowing it, as his wife Ellen is having an affair with Hooper, giving us the idea of 1970s masculinity in crisis: is it too much to view the shark as an altogether different kind of moby dick? Certainly Halloween and Alien echo with primal sexual fears and unpleasant psychosexual overtones; how different is Jaws?

That said, Benchley had a stickier end in mind for Hooper than Spielberg did. Rather than the keen young scientist merrily swimming off into the sunset with Brody, as he does in the film, in the novel he ends up as just another snack for Bruce. Thus the moral code that horror movies traditionally work from (‘bad people die badly’) is upheld in the book if not the film.

But the true horror lies in Spielberg’s film, not the book. It is worth reiterating how disturbing this film is. The marine fountain of gore that heralds the death of Alex Kintner on an inflatable lilo, as well as the horror of his mother’s reaction to his death, are both genuinely awful to witness. When the mother, played by Lee Fierro, slaps Brody in the face for his complicity in her son’s demise, the actress does it for real, and painfully hard: you almost feel it yourself.

On release, Jaws was given a curiously lenient ‘A’ rating in the UK. Until 1982, that rating meant ‘Advisory’, allowing kids aged five or over into the cinema while it was “not recommended for children under 14 years of age”. Five years old?

In the USA, meanwhile, Jaws was released with an equally feeble PG certificate, causing the Los Angeles Times to complain that “the PG rating is grievously wrong and misleading… Jaws is too gruesome for children and likely to turn the stomach of the impressionable at any age.” In a rare display of humour, the Motion Picture Association of America defended the rating by quipping: “Nobody ever got mugged by a shark”.

Judging by the evolution of horror cinema in the 80s and beyond, these permissive age ratings were significant, because they enabled a whole lot of youthful future screenwriters and directors to see Jaws at a formative age. When the time came for those kids to make their own films, a lot of them were about sharks, for obvious reasons: you’ll no doubt be familiar with Deep Blue Sea (1999), The Shallows (2016), The Meg (2018) and the rest of them.

Horror films that reused the broader, motiveless-killer idea from Jaws and/or Halloween proliferated too. If you’ve read this far you’ve probably seen at least one of The Driller Killer (1979), Friday The 13th (1980), Maniac (1980), An American Werewolf In London (1981), A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984) and the endless sequels that followed most of those. All of these were far more graphic than Jaws.

By the 21st century bloodbath culture has become the norm on TV and the internet. Horror, and graphic horror, has been a part of everyday mainstream culture for decades now, whether you personally enjoy it or not. That is the true legacy of Jaws. Happy 50th birthday, Bruce.