So much contemporary experimental music seeks to do the theoretical work that was once the domain of philosophers, and Lee Gamble always looms large in the minds of those who approach music like a philosophical problem. An unabashed lover of big ideas and concepts, Gamble is the embodiment of Kudwo Eshun’s “conceptual engineer”: his music is an array of freefloating ideas and theories that peel away the ambiguous layers and in-between spaces in contemporary life by manipulating the spatiotemporal qualities of sound. His early releases, Diversions 1994-1996 and Dutch Tvashar Plumes, contained an elusive nostalgia and recalled old rave rituals, while 2014’s Koch stripped the vitalism out of techno productions leaving the warped and bombed-out shells of dance music culture. His more recent releases, 2016’s Chain Kinematics and 2018’s Mnestic Pressure, saw his ideas land on terra firma as the mist and fog around his productions gradually cleared, leaving an austere but complex amalgamation of styles, from jungle and 2-step to techno and IDM.

Now he’s matched his complex, jarring music to the overwhelming sounds and sights of the city – a phenomenon Gamble refers to as a “semioblitz”. The idea of the city as the subject or main character in art or text is not a new one; from the elegant avant garde of Metropolis to Koyaanisqatsi’s pantheons of industry and energy to the bloated technocapitalist chaos of Bladerunner, the citizen is subject to spaces that seek to become self-sufficient, intelligent, operationally efficient, regulating machines – panopticons run by machines for machines.

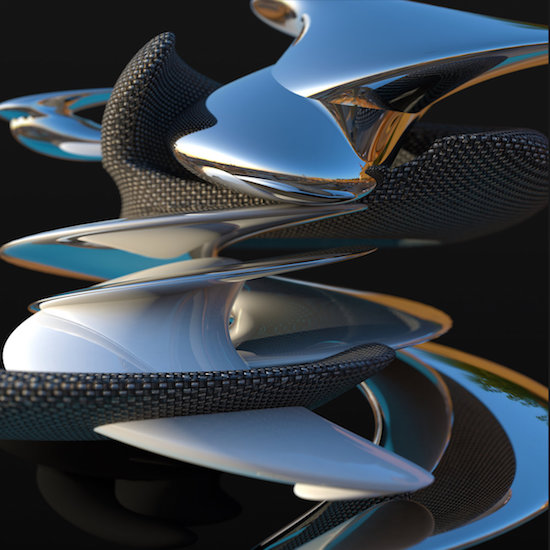

It is these tensions between order and chaos that Gamble seeks to articulate with In a Paraventral Scale. He seems to move on from the great western cities of the 20th century – New York, London, Berlin – and head to Shanghai, Moscow and Dubai, places that house a volatile mix of accelerationist capital and one-party state politics. These places, glistening and expansive amalgamations of non-places, have taken the old spectacles of speed and electric-powered modernism and added rhizomic layers of augmented hyperreality, to give a multiplicity of white-hot impersonal affect that is euphoric but dispersed. (This is evident in the album’s cover art, where the sharp industrial lines of 20th century modernism are replaced by liquid curves that typify the new smart digitised metropolis.)

In some senses, the album follows a narrative path. ‘Fata Morgana’, with its metallic drones and stannic blares, sees life breathed into this sonic city as the sun rises and hits the vistas of steel and concrete, before giving away to woozy new age lines and distended trumpets. The track has a luscious, almost moist, feel to it that’s reminiscent of the dewy retrofuturistic music of Vangelis’s Blade Runner soundtrack.

From here, In A Paraventral Scale tracks the workings of the city space in action. And this city is one based on computation, information and augmented reality. ‘Folding’ is a delicate collection of interlayered electronics melodies that drip to algorithms that don’t necessarily follow any determinate pattern as the processors tickety-tick away in the background. ‘In The Wreck Room’ also shifts and morphs relentlessly, as patterns and forms glance off neon surfaces and slivers of rinsed jungle percussion rattle and vibrate.

The most interesting section of In a Paraventral Scale are where we hear and feel the movement and flow of bodies and vehicles. ‘Moscow’ flickers into life with fluttery arpeggios before it launches into a of hi-NRG electro and glides along the city’s highways with frictionless ease. On ‘BMW Shanghuan X5’, named after the infamous Chinese car model accused of copying the BMW X5, we hear the sounds of manipulated de-tuned high-performance car engines and synthetic helicopters, a mini-symphony of the machinic noise and grind that still exists in an era that aims to have information and objects move with fluid calm.

And what about the people? Without them, we are listening to an empty concrete shell with bleeping machines. There is a human dimension to this album, but it feels notably reduced to that of a facilitator or a passenger among the city’s flows. Phrases such as “I just got the idea to chant more everywhere” over the crackly, phasing fugues of ‘Chant’, or a woman repeating “ghosts” like a footwork sample, drift in like corroded and glitchy spectres, ghosts from the old meatspace. This album seems to suggest that while people do play a part in Gamble’s idea of modern spaces, the citizen has been replaced by the inforg – the human/electronic hybrid who is fully meshed and dispersed into the network. The personal, the individual, has become a cluster of abstract registers.

At just 25 minutes, In a Paraventral Scale gives only a glimpse of what it means to exist and participate in these urban and virtual corporatised spaces. Gamble is onto something, though, and this first part of three is – I hope – an introduction to something even bigger lurking beneath.