Bananarama were pop’s rowdy girl group of the 80s, with a classic punk sensibility. Their 1983 performance of ‘Cruel Summer’ on Top of the Pops is testament to that – the three women, dressed in black and white, loll over a railing, laxly bop around on stage and make minimal effort to hide the lip-syncing TotP acts had to do – Sara Dallin doesn’t even hold her mic aloft. Their hair stands to attention with the help of more than a few Elnett spritzs, their smiles are wide, their sunglasses dark, their attitudes set on colossally not giving a fuck. Their slapdash, wild-limbed dancing is more post-4am final club tune than teatime on a Thursday night. This was almost a decade before Nirvana’s own classic, piss-taking performance; in 1983, The Clash fired Mick Jones, The Misfits and Undertones disbanded, the first Now… compilation was released, and pop was revelatory with wunderkind producers and synthy new sounds pushed by the Eurythmics, Bowie and Duran Duran.

Childhood mates Keren Woodward and Sara Dallin met Siobhan Fahey in 1981 – she was on the same journalism course as Sara in London. Their magic brewed above the Sex Pistols’ Denmark Street rehearsal space – Paul Cook had said they could move in when they were faced with homelessness. The three of them lived there while doing scrappy impromptu sets and backing vocals for everyone from Iggy Pop to The Jam, and finally recorded their first demo ‘Aie a Mwana’, a Bad Blood cover sung in Swahili, which they learnt phonetically. They briefly considered calling themselves The Pineapple Chunks but then were inspired by a Roxy Music song. Next thing, ‘Aie a Mwana’ was their first underground hit, released by Demon Records (who later stabled Suede, Belinda Carlisle). It caught the attention of The Specials’ Terry Hall, who got them singing backing vocals on a Fun Boy Three album. Invigorated by more press attention and dynamic opportunities, Bananarama dropped debut album Deep Sea Skiving.

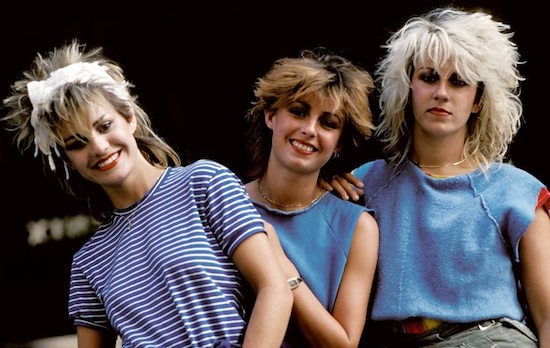

The trio hit a wild, dazzling peak that pierced pop’s clouds, somewhere between the Shangri-Las and the Slits, Shampoo and the Spice Girls. They weren’t a malleable girl group or passive ornaments that bigwigs and male producers could whittle away at. (“They had so many opinions,” Pete Waterman apparently complained – he produced three of their slicker later albums.) Terry Hall lightly described them as “impossible”, kicking them out of recording sessions in fits of giggles. They were banned from primetime TV shows for raucous behaviour, performed gleefully ironic self-choreographed dance routines in handmade punky clothes, and made huge hits while riding waves of vodka tonics. They were whip-sharp and deadpan in interviews, always in on their own joke. They were loads of fun, and were laser-focused on making the sounds and choices they desired.

The self-assured chaos was part of an enchantment they unleashed on an adoring public, kicking off a slew of hits with Deep Sea Skiving to Bananarama, True Confessions and Wow!, clocking up over 40 million sales worldwide and more chart scores than Spandau Ballet, Depeche Mode and their other 80s peers. It was a self-steered shambles and a success that railed against the uber-calculated girl power image and po-faced Joy Division successors, baffling their label who had no blueprint for a band like them. The band rebuffed management offers from Malcolm McLaren – who wanted to take them in a ‘sexier’ direction – in favour of Hillary Shaw, a legend of a manager who later looked after Girls Aloud.

They confidently oscillated from fun-loving covers to songs like ‘Cheers Then’ – their first self-composed song that highlighted their ability to make deep-feeling, minor-key songs about broken relationships, giving fresh perspective to tired pop cliches. Bananarama triumphed with darker themes again on megahit ‘Robert De Niro’s Waiting’, a song about rape and safety from their monumental 1984 second album, while ‘King of the Jungle’ paid tribute to friend Thomas Reilly, brother of Stiff Little Fingers drummer Jim Reilly, who was shot and killed by a British soldier in Belfast. On ‘Rough Justice’, from the same record, they sing about domestic violence and poverty. They approached the pop stratosphere once against with SAW-steered, shiny third and fourth LPs that housed ‘Love in the First Degree’ and ‘I Heard a Rumour’. Their huge cover of ‘Venus’, with its temptress-filled, surreal video, showed a wonderfully campy side to the group that’s found its way into cult movies (Romy & Michele’s High School Reunion) and some other artists’ more questionable versions.

The move away from their kinetically DIY roots saw Fahey depart in 1988 after Wow!, then there were several line-up changes, a mammoth tour, and dips into everything from acid house to flamenco across multiple other albums. While Pop Life (1991) was more glamorous than the Bananarama we once knew, it’s still defiant, care-free contemporary pop. Bananarama held court at the same time as early U2 and late Rolling Stones, when rock stars were revered. They were never held in the same esteem as those bands, of course; they didn’t fit the ‘classy female singer-songwriter’ category adn they weren’t allowed into the rowdy boys club either. “People accept it from boys because that’s the way boys in bands are supposed to behave,” Woodward told Q magazine. “When it’s these cute girls who are reasonably pretty and jump up and down on the telly, they can’t take it.”

Bananarama fought still-raging battles for women in music, and they had fun while they did it. Their pop was guerrilla, made shambolically, sometimes on the dole and sometimes cocking a snook (and a cowbell) at an uncooperative producer with creative differences, but always offering something that shook the tree-tops of British music.

Deep Sea Skiving (1983), Bananarama (1984), True Confessions (1986), Wow! (1987), Pop Life (1991) and Please Yourself (1993) are out now