For over two decades’ sustained brilliance, Deerhoof have constructed a dayglo, upside-down world in which nothing is ever quite what it seems, where nursery rhyme-grade playfulness is often freighted with echoes of man’s inhumanity to man and the system’s essential injustices and their embrace of brash power-pop form and dynamic is regularly interrupted by blasts of avant-garde dissonance and distortion. This, after all, is a group whose most immediately accessible opus, Apple O’, haunts its joyful 1968-vintage-The-Who-meets-Bad-Moon-era-Sonic-Youth-meets-Melt-Banana pell-mell with nightmarish visions of nuclear holocaust, a band that’s winningly giddy and also thoroughly conversant with the horrors of life in the 21st century.

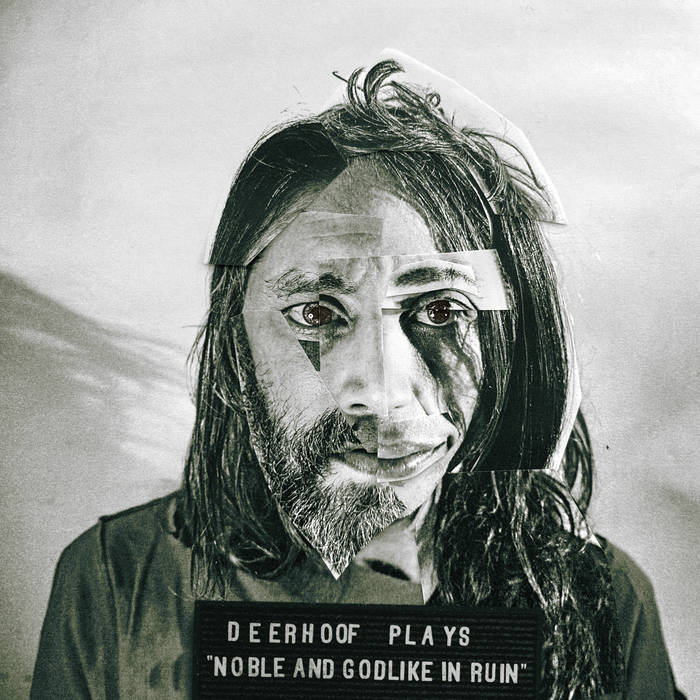

Their nineteenth album, Noble And Godlike In Ruin, is as gleefully perverse and perversely gleeful as anything in their catalogue, swinging between pop and noise like they aren’t opposed concepts, but rather points of equal value along a spectrum that the band ricochet across with sublime abandon. The album opens with birdsong, Satomi Matsuzaki murmuring “Love is all”, channelling the dreamy bossa nova of Joyce Moreno over gently rumbling spiritual jazz and broken folksong recalling Illuminations-era The Pastels. What follows is a hurricane of anarchic invention and unforced tunefulness, often at once. A pulsating, rhythmically compulsive groove routinely collapses into car-wrecks of black noise and undigested chunks of ‘Nessun Dorma’ (‘Under Rats’, a collaboration with Saul Williams). On ‘Ha, Ha Ha, Ha, Haaa’, perilously descending fusion basslines and hypnotic math-rock guitar figures are anchored by Greg Saunier’s ever-gripping percussion (Saunier is a marvel throughout, finessing Keith Moon’s hyperactivity, John Bonham’s heaviosity and Elvin Jones’s angular unpredictability into a fluid rhythmic lexicon all his own; I could listen to him drum the phone-book). Unfailing pop knack, gleefully upended with structural subterfuge, a trick Deerhoof repeat ad infinitum but never to the point of nauseum.

Noble And Godlike In Ruin arrives at a bruising nadir in history, where governments brazenly treat inconvenient life as kindling, where technology seems tirelessly engaged in dystopia-construction. The album title indicates Deerhoof are all too aware of this needling speed-run through mankind’s bleakest pasts, and how precarious this leaves the whole shebang. These paradigmatic shocks inform and shape the lyric sheet, though the group resist polemic in favour of subtlety, storytelling and metaphor. ‘Kingtoe’ eavesdrops a conversation between robot and fleshy inventor, divining existential despondency within each; the blackly comic ‘Ha, Ha Ha, Ha, Haaa’ finds Matsuzaki chirruping “atomic bombs / beautiful but terrific”; ‘Disobedience’ fantasises of “mutiny at dawn”. ‘Sparrow Sparrow’, meanwhile, simply concludes that “hope dies”.

The album closes with ‘Immigrant Songs’, its most incisive lyric, an ‘us and them’ tale from the POV of the vulnerable immigrants trying to survive within such a cruelly hostile environment. Her intent sharpened by the guilelessness of her vocals, Matsuzaki – an immigrant herself – gives voice to the invisible migrant workers keeping the system going under threat of deportation, abuse and worse by that very system. “I was the driver of the guests to your party!” she declaims, the injustice within this servile relationship poisoning the interaction. The song she sings at the party is “happy to you / depressing to me” and, by the end, she’s deciding “this song we sing / won’t be for you”. The track then follows the sweetest three-and-a-half minutes of the album with a climactic three-and-a-half minutes of howling feedback, thrashing drum and anguished human screams. It’s their version of Eugene McDaniels’ ‘The Parasite (For Buffy)’, its scourging aftermath an answer to modern America’s cruel inversion of The New Colossus’s promise of open arms to “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore”. Concise and ambitious, delivering its poisonous punch with characteristic sweetness, the track and the album it concludes are inarguable proof of Deerhoof’s unerring genius.