‘Some enchanted evening / You may see a stranger / Across a crowded room /

And somehow you know / You’ll see her again and again’

Rodgers & Hammerstein – ‘Some Enchanted Evening’

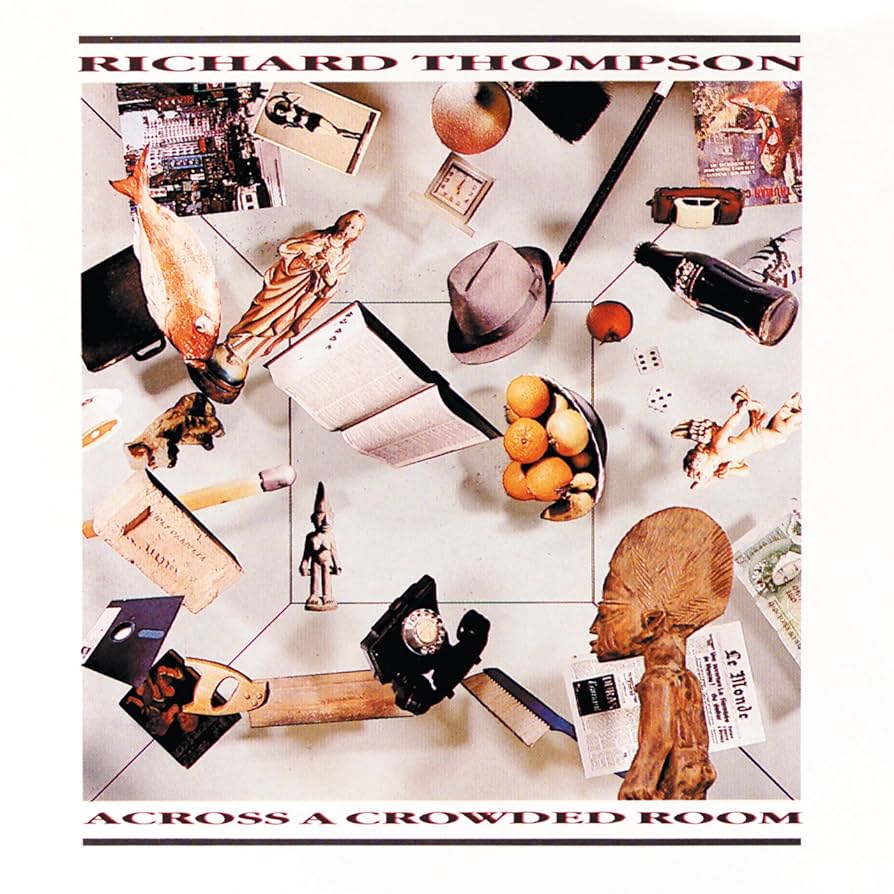

Released 40 years ago this week, Across A Crowded Room was pivotal for Richard Thompson. It was his first solo album for a major label (and his second since parting from Linda Thompson, his wife and musical partner of ten years). It would also be the last solo album he’d record exclusively in the UK and the last he’d make with producer Joe Boyd (who’d first clapped eyes on a 17-year-old Thompson playing guitar for Fairport Convention in July 1967, practically signing the band on the spot). And while Thompson’s work with Fairport Convention and the albums he recorded between 1972 and 82 with then-wife Linda are rightfully lauded, his solo albums don’t enjoy quite the same acclaim; when Across A Crowded Room was released in 1985 it was met with a relatively muted response. And yet it is a work of subtle, off-kilter beauty, recalling at times the frazzled alienation of John Cale’s Island Trilogy; the jangling intensity of early REM; the abstract darkness of mid-80s Scott Walker. What’s more, the North American leg of the promotional tour produced a live album (Across a Crowded Room Live at Barrymore’s 1985) that deserves to be spoken of in the same breath as similarly hard to find holy grails like Jerry Lee Lewis Live At The Star Club, Hamburg and The Complete Miles Davis At The Plugged Nickel (no, really).

But first, the studio album. Recorded in London during September and October of 1984, Thompson was joined on the Across A Crowded Room sessions by Fairport alumni Simon Nicol and Dave Mattacks (on twelve-string Rickenbacker and drums, respectively). If the previous year’s Hand Of Kindness can be described as an album bursting with an infectious enthusiasm and an abundance (some might say an over-abundance) of humour, its follow-up is a far more fraught-sounding affair. Joe Boyd’s production gives the album a glistening post punk shimmer, warm and cool at the same time, and the songs bristle with a kind of desperate energy – touching upon themes of jealousy, betrayal, lovelessness and obsession – making the album seem more a continuation of Richard and Linda’s strung-out swansong, Shoot Out The Lights, than a development of Hand Of Kindness. Which is strange, given that Hand Of Kindness was recorded in the immediate aftermath of Thompson’s separation from Linda, whereas Across A Crowded Room was recorded and released either side of his second marriage to a new American love, Nancy Covey. As a result, armchair-psychologists may be tempted to hear Hand Of Kindness as the release of pent-up emotions, and the celebration of finally being out of a situation that was making Thompson unhappy, and Across a Crowded Room as the hangover from that celebration. The sound of a new reality taking hold; new responsibilities, new beginnings, a lingering sense of guilt. Its title’s nod to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s romantic standard from South Pacific feels cloaked in irony.

“Opening track, ‘When The Spell Is Broken’, suggests they could be on to something. Over a brooding mid-tempo groove (augmented by Christine Collister and Clive Gregson’s sublime harmony parts – more of which below), Thompson wearily recounts the struggle to keep the magic of love alive:”

When the spell is broken

All the joy is gone from her face

Welcome back to the human race

How long can the flame

Of love remain…?

It is a solid, if unspectacular opening. But then, around the two and a half minute mark, Thompson plays a solo of such disarming simplicity and inventiveness, it is as if the song has been cracked open, inviting the listener inside. And with admission granted, the album proper begins.

Incongruously pairing a jittery motoric beat with an urgently declarative vocal from Collister, ‘You Don’t Say’ is a disorientating slip of a song. The intro becomes a verse and the verses refrains, so that Collister is effectively smuggled in as lead vocalist; subterfuge perhaps deemed necessary to avoid drawing comparisons with Linda, against whom Collister comfortably holds her own. (That the song is constructed as a call-and-response with Collister informing the singer about an “old flame” who is accusing him of using her and then leaving her for another, gives the song a pleasingly meta frisson.) In fact, the harmony parts she and Gregson deploy throughout the album are integral to its artistic success. They work perfectly with and against Thompson’s gruffer vocals, bolstering and sweetening them, thus providing him with arguably the most intuitive vocal accompaniment of his career. Thompson himself freely admits he was not “born with a voice”. Indeed, over the next few years it would noticeably thicken into the somewhat blustery vocals of today, but here he is in fine voice, his vocals still relatively youthful and limber.

The forward momentum of the album is maintained by ‘I Ain’t Going To Drag My Feet No More’: a rousing note-to-self with horns providing muscle and an accordion-led instrumental break which explains why REM were so keen to work with producer Joe Boyd for that year’s Fables Of The Reconstruction. The song climaxes with a thrilling crescendo which threatens to send Thompson’s vocals spiralling into the blood-flecked realms of John Cale at his most paranoid, before pulling back from the brink and fading out on a suitably taut and wiry guitar solo. A final forward thrust before momentum temporarily stalls.

To call the song that closes Side A as the “highlight” of the album would be misleading. Rather, the Myra Hindley and Ian Brady-inspired ‘Love In A Faithless Country’ is the album’s sticky black heart: where all movement freezes and every light goes out. (It is interesting to note that The Smiths’ more overt treatment of the same subject-matter, ‘Suffer Little Children’, had been released only a year before.) Over a skeletal arrangement that’s all angular guitar lines, marauding bass and vast swathes of empty space, Thompson croons an enigmatic lyric like a cross between Nick Cave and Climate Of The Hunter-era Scott Walker:

Always move in pairs and travel light

Loose friend is an enemy, keep him tight

Always leave a job the way you found it

Look for trouble coming and move around it

The song’s elliptical refrain, “That’s the way we make love” is made even more chilling by histrionic vocal ensemble The Soultanas, whose response, “Lösch mir die Augen aus” cuts through the song like the lacerating guitar solo it bookends. (Live, Thompson would transform this solo into a kind of sinister waltz.) That this snatch of German is the title and first line of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem of obsessive love, ‘Put Out My Eyes’, serves to darken the song even further. In fact, so dark is this song that it only takes a single couplet to cast its pall over the album’s title; that Rogers and Hammerstein allusion no longer merely ironic, but suddenly twisted into something far more unsettling, from South Pacific to Saddleworth Moor…

Learn the way to melt into a crowd

Never catch an eye or dress too loud

The song ends with the opening line of Rilke’s poem finally resolved – “Lösch mir die Augen aus: ich kann dich sehn” (“Put out my eyes, and I can see you still”) – recalling, again, ‘Suffer Little Children’, and its own equally haunting refrain: “Hindley wakes, and says: ‘Oh, whatever he has done, I have done’.” It is perhaps the most singular song Thompson has ever written.

‘Love In A Faithless Country’ would be a difficult act for anyone to follow, and though the album’s second side struggles to escape from its shadow, there is still much to enjoy: the green-eyed confessional that is ‘Fire In The Engine Room’ – an extended metaphor that’s all tightly-coiled dynamics and a curiously cynical view of marriage for a newly-wed (“And you know how uncertainty can linger / with a rattlesnake wrapped around your finger”); the swaggering anti-Thatcherite call to arms ‘Walking Through A Wasted Land’; the throwaway notebooks-out-plagiarists exuberance of ‘Little Blue Number’; and then there’s ‘She Twists The Knife Again’…

Yet another song dealing with failed relationships, ‘She Twists The Knife Again’ strikes something of a sour note. Its scathing lyrics (“She can give it out, she can’t take it…”) are hard to listen to without thinking of Linda (whose own solo album, One Clear Moment, was released around the same time). In a 1986 interview with Musician magazine Richard Thompson spoke defensively against “neutering” the song. He advised listeners that they shouldn’t take it as “a direct song about my life – it’s a kind of story. It’s fiction,” before conceding, “Well… it’s a faction.” (Live, he would occasionally turn the lyric against himself: “She knifes the twit again”.)

Perhaps in atonement for the previous song’s regrettable lapse into misogyny, the album ends with ‘Ghost In The Wind’, a quietly devastating portrait of loneliness. While guitars sigh and moan all around him, the singer forlornly asks, “When will my sore heart ever mend?” And then, a mere 38 minutes after pressing play, it’s over: not with a bang, but an exquisite whimper.

Now, a brief word about the double live album, Across A Crowded Room Live at Barrymore’s 1985. As video footage shows, the previous year’s Hand Of Kindness tour was clearly a lot of fun for all concerned. Thompson is fronting his so-called Big Band (the standard two guitars, bass and drums line-up expanded by two horns and an accordion), whose high-spirited romp through Thompson’s back catalogue is a joy to behold. But the difference between 1984’s Big Band and the musicians captured at Barrymore’s on the evening of April 10 1985 is startling. If the Big Band are playing out of sheer joie de vivre, the 85 band are playing as if their lives depend on it. The horns and accordion are gone, as are old Fairport muckers Nicol and Mattacks. Instead, the rhythm section comprises new recruits Rory McFarlane (bass) and Gerry Conway (drums), with backing vocals and additional guitars provided by Gregson and Collister (whose solo spot, ‘Warm Love Gone Cold’ is one of the album’s highlights, a Weimar-esque torch-song reimagined via side two of Low).

The result is one of those live albums that seems to have captured the songs while they’re still giving off the white heat of their creation; one of those live albums that feels as if it were recorded outside of the band’s comfort zone, at some godforsaken place near the end of the world (in this case Ottawa, Canada) by a band armed only with a bloody-minded self-belief and a sense of something to prove. (Thompson is firmly in Link Wray meets Tom Verlaine mode throughout.) As a study in sustained tension, Live At Barrymore’s is up there with Bob Dylan’s Hard Rain, Galaxie 500’s Copenhagen and The Fall’s A Part of America Therein. And production-wise it makes other documents from this tour – the semi-bootleg Live At Nottingham and Thompson’s own release, Faithless – pale in comparison. Needless to say, it is absolutely essential.

Anyway, Across a Crowded Room entered the charts at number 80, remained there for two whole weeks, then quietly disappeared. Richard Thompson and Joe Boyd parted amicably, both agreeing that they had taken their professional relationship as far as they could. Then, his eyes now fixed more firmly than ever on the American market, Thompson proceeded to work with producer Mitchell Froom, whose stable of US-based session musicians gave subsequent albums a slicker, more radio-friendly sound. Finally, in 1991, Thompson released Rumor And Sigh: the Grammy-nominated cross-over album that allowed him to join the ranks of rock’s elder statesmen, where he has comfortably (perhaps too comfortably) remained ever since. But spare a thought for the low-key mid-career masterpiece that is Across A Crowded Room, and its bruised and bloodied sister album, Live At Barrymore’s, 1985.