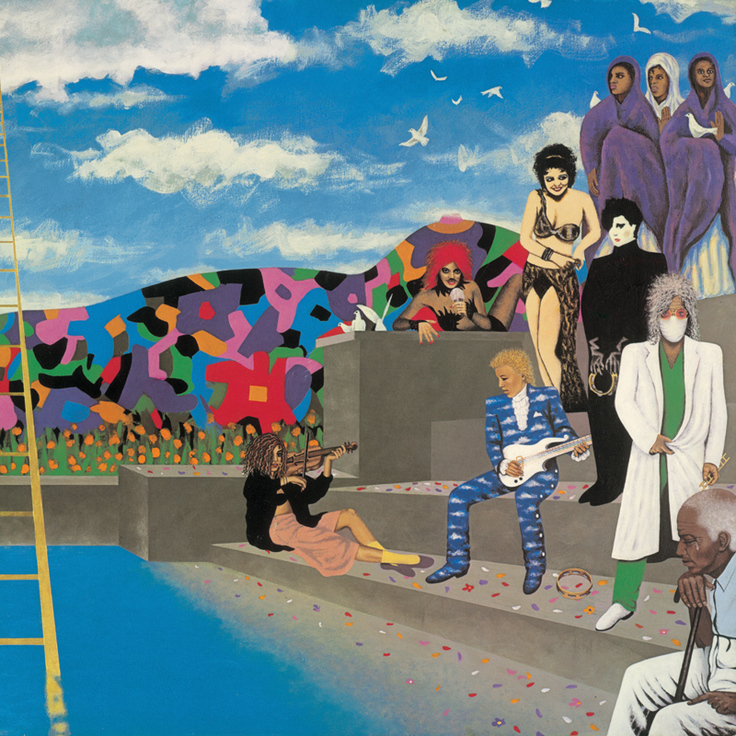

While it’s curious that a transatlantic hit and American number one album should be comparatively forgotten, Prince’s 1985 Around The World In A Day is undeniably a curious proposition – which is what’s glorious about it. Remembered mainly as the source of US hit ‘Raspberry Beret’, the album’s UK single ‘Paisley Park’ doesn’t even merit inclusion on most Prince compilations, while third single, ‘Pop Life’ bombed in Britain. The critical confusion the album caused on release was, hence, more indicative of its future fate than its inevitable commercial success as follow-up to 1984 smash Purple Rain. For what a curious follow-up it was – a kaleidoscopic psychedelic soul confection, suffused with ouds and cellos, packaged in trippy Sgt. Pepper-style cover-art, released at the height of 80s hippyphobia and synthophilia. Non-conformist in a conformist age, Around the World doesn’t just transcend its period, it’s transcendent, period, a prime product of Prince’s purple patch. Because from 1979’s Prince to 1991’s Diamonds And Pearls, Prince had the most astonishing decade-owning run this side of The Beatles’ 60s or Bowie’s 70s (we’re excluding the Batman OST on a technicality). While looking to the past on Around The World, Prince could still, at this career-peak, exemplify not just the present but the future too.

The adage “never trust a hippy” was part of punk’s year-zero reset. Yet it was the mid-70s recession rather than its product, punk, that ravaged the counterculture’s reputation, as hippie breadheads like Crosby, Stills & Nash and Emerson, Lake & Palmer paraded a bloated caricature of a post-war plenty no longer available to ordinary people. The countercultural ground was already infertile before Reagan and Thatcher came to salt it, therefore, castigating the 60s’ “permissiveness” and lawlessness, while reversing the 60s’ political gains. Hippies’ plunging stock can be observed in The Big Chill’s characters’ patronisation of their 60s selves, in Ad Rock smashing up a nerd’s acoustic guitar in the Beastie Boys’ ‘Fight For Your Right’ video, and in the cruel caricature of hippie Neil in British TV comedy The Young Ones. This cordon sanitaire around the psychedelic 60s did have its rebels, however, like LA’s psychedelic Paisley Underground (The 3 O’Clock; The Rain Parade): the name of Prince’s new label and 1985 single (and ultimately his recording studio and home) weren’t coincidental, given his donation of ‘Manic Monday’ to Paisley alumni The Bangles. Yet ‘influence’ is always less interesting than what lies behind such a cultural congruence. For a muted hippie nostalgia is also tangible in Don Henley’s ‘Boys Of Summer’, Bryan Adams’ ‘Summer Of 69’ and XTC’s Skylarking – as well as Prince’s own ‘Take Me With U’ – questioning the new consensus, hinting at what was being lost in this era of acquisition.

From the get-go, Around The World In A Day is a refutation not just of 80s pop but of 80s politics – in sound (the finger cymbals, darbukas and ouds wafting from the opening track), vision (that psychedelic cover), and sentiment. ‘Around The World in a Day’ is a secular take on The Impressions’ ‘People Get Ready’, filtered through the druggy, one-note utopianism of The Beatles’ ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ (“open your heart / open your mind”): promising that, amid 80s profiteering, “laughter is all u pay”. Those dabs of exotica aren’t just at odds with 80s synth saturation, but with the chauvinistic nationalism of Reagan’s America. The song’s funk guitar breakout, meanwhile, is a reminder that psychedelia was never as white as it’s painted. Prince stands in a lineage of Black psychedelia running through Love, Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Curtis Mayfield’s Curtis (1970) and the Temptations’ Psychedelic Shack (1970). The Family Stone were the model for The Revolution, the male-female, Black-white lineup of each aggregation exemplifying countercultural collectivity.

‘Paisley Park’ flows seamlessly from the title track, with its finger cymbals and violins, but adds a touch of rock crunch, via a grunting count-in and woozily feedbacking guitars, which split the difference between Jimi Hendrix and Syd Barrett. It’s some of Prince’s career-best axe-bothering. Despite this blast from the past, the song also sounds entirely 1985, with its processed Linn drums and wobbly DX7 synth-pulse, humanised by being just slightly out of time. The past-present combination makes the track seem disembodied, hazy, hauntological: simultaneously ectoplasmic and corporeal. With paisley being the pattern of 1967’s Summer Of Love, the lyrics hymn a utopian space “of profound inner peace” and exult that “love is the colour this place imparts”. “Love” is deployed here in the collective rather than personal sense, as on The Beatles’ ‘All You Need Is Love’, or Love’s “I could be in love with almost everyone”. Just as ‘Paisley Park’s music contains contradictory elements, so do the lyrics, being as melancholic as they are ecstatic, confronting contemporary reality amid countercultural escapism. The verses detail a woman mourning the husband who betrayed her and a man whose home is condemned under 80s destructive “regeneration” (aka gentrification). 60s values are offered as a salve for 80s ills, here, private pain salved by the Park’s collective panacea. Parks were often derelict in the 80s, but were central to the 60s: the Love-In and anti-Vietnam protests at LA’s Elysian Park, the 1967 Human Be-In at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park; the derelict Berkeley land developed as People’s Park, which California governor Ronald Reagan evicted by force in 1969. While the lyric acknowledges that Paisley Park is “nowhere” – a “no place” as anti-utopian cynics insist – it situates imagination as aspiration (“Paisley Park is in your heart”). Watch the trippy Sesame Street video though – kids in McGuinn shades and kaftans laughing and delighting in play – and it feels entirely graspable.

‘Paisley Park’ has been eclipsed in popular memory by ‘Raspberry Beret’, another 60s/80s mishmash with an atavistic count-in, but the 80s element comes from its narrative perspective not – beyond the Linn drums – the music, which is sheer string-swept, 12-string psych giddiness. The narrative is as vaporous as patchouli but, relayed in the mythic register, it becomes epic, allegorical, as its trippy video confirms. While the brightly behatted hippie chick is carnally physical (“if it was warm she wouldn’t wear much more”), she’s also airily metaphorical: free in love (“she knew how to get her kicks”) and in spirit (“she came in through the out door”), a female figuration of the counterculture like Leonard Cohen’s ‘Suzanne’. In creating such songs about women who are equal parts sex object and muse, with female backing vocalists always singing the melody rather than a harmony, there’s a little-noted commonality between Prince and Cohen, another 60s/80s tie-in. In the song, the flower child and Prince’s dropout lover ride his motorbike “back to the garden”, through old man Johnson’s farmland, with the elemental climax combining the erotic and the mythic as the pair make love in a storm-lashed barn: “thunder drowns out what the lightning sees”. Yet there’s an aching melancholia framing the song’s infectious joy, because, years later, the narrator is still haunted – not just by the girl but by what she represents: lost youth, the traduced counterculture that tried to make youth’s optimism and freedom perennial.

In a similar musical vein to ‘Raspberry Beret’ ‘Pop Life’’s confectionary lightness sugars darker sentiments. That darkness isn’t the downside to fame that most critics discern, though, but a snarky depiction of the period’s pampered pop aristos snorting coke and whining about minor inconveniences – “is the mailman jerking you around?” – amidst the period’s growing poverty. ‘Pop’ here isn’t just music, or fizzy pop, but life’s effervescence, which the song insists should be available to all – “everybody needs a thrill” – when, in the 80s, even hedonism was unevenly distributed. ‘Pop Life’ marks the first time Prince really addressed social issues, although there’s a line of descent from ‘Ronnie Talk To Russia’ through ‘1999’ to, on this album, ‘America’’s declaration that “Communism is just a word / But if the government turn over / It’ll be the only word that’s heard”. While seemingly urging defence of the United States against the Soviet Union, the song’s enumeration of the growing gap between rich and poor – “little sister making minimum wage” compared to Wall Street “aristocrats on a mountain climb / Making money” – means it could equally be invoking communist revolution (note, again, the name of Prince’s band). With the song’s Jimmy Nothing refusing to pledge allegiance to the flag in classic countercultural protest, the line “Now Jimmy lives on a mushroom cloud” invokes the ghetto narcosis as America waged internal Cold War against its African American population, first with heroin, then with crack. Musically the track is a Hendrix-suffused psychedelic rocker, and if not the catchiest melody on an album full of them, its overamped electric guitars are engagingly at odds with the slap-bass, ricocheting Linn drums and chintzy synth.

‘Condition Of The Heart’, by contrast, boasts one of the album’s most gorgeous melodies, and the track – just Prince on multiple overdubs – is an explosion of rippling pianos, otherworldly synths, rumbling timpani and heartrending harmonies. While there’s nothing overtly 60s about the track, the yearning of ‘Raspberry Beret’ and melancholy of ‘Paisley Park’ become central in this lament for lost loves. ‘Condition Of The Heart’ peaks, in this most material of eras, with “sometimes money / Buys you everything and nothing”, while in a call forward to ‘Nothing Compares To U’ and a callback to the 60s, he’s spiritually tripping out to the daisies in her yard – the heartbroken hippie. ‘The Ladder’ is even more yearning but, as one of few songs on the album to feature the full Revolution, it’s also anthemic, a ‘Hey Jude’ pop-gospel hymnal for the 1980s. “Everybody’s looking for the ladder” the whole band sings, “Everybody’s trying to find the answer.” The sentiment here is questing and spiritual in an era when yuppies, financiers and Madonna thought they had the answer, that they’d found the ladder, and you could literally take it to the bank. But The Revolution’s ladder is both spiritual and collective: “The size of the whole wide world will decrease… And time spent alone, my friend, will cease.”

The album’s concluding ‘Temptation’ appears to be at odds with the hippie-dippiedom which precedes it, a rerun of Prince’s pocket-sized perv shtick, as an opening guitar wank-fest becomes a funk-rock grind, topped with P-Funky horny horns. But for Prince, like George Clinton, sexual freedom always brought liberation beyond the bedroom. “I wish we all were nude / I wish there was no black and white / I wish there was no rules” as 1981’s ‘Controversy’ had it. The Revolution was never just a sexual revolution. So Prince has much in common with the hippies’ favourite philosopher, Herbert Marcuse, who coined the concept of ‘Eros’, the life-drive, which sublimated sexual release as a universal pleasure principle, unmediated by alienation, competition or subordination. So, while ‘Temptation’ appears to be abhorring the weakness of the flesh compared to the purity of the spirit, to see what’s at stake here as Eros rather than simply sex better fits the song’s status as the concluding track of such a utopian album. The booming, subterranean voice of God who condemns the lustful subject to death is, hence, the voice of society – like the baritone intoning “no dice, son, you’ve gotta work late” on Eddie Cochrane’s ‘Summertime Blues’. So we’re surely not to take the lover’s response as sincere when he whimpers ingratiatingly that “love is more important than sex”. As the 60s hippies who urged “make love not war” knew, the countercultural and carnal uses of ‘love’ are related, rather than, in the cutthroat ethos of the 80s, being in competition. Prince’s entire career was an attempt to synthesise the sacred and the profane, the lustfully erotic with the spiritually ecstatic. Around The World In A Day is that lifelong countercultural project at its most countercultural sounding.