In Raven Chacon’s music, listening is about paying attention to silence as much as sound. The composer, performer and installation artist presents this dichotomy across experimental noise, chamber and installation works that unfold through layered timbres and ample rest. His pieces leave space for ideas to emerge in moments that could seem, at first, like quietude. But listen closer and find that so much lives inside: the weight of history, the power of protest, the resonance of performing spaces.

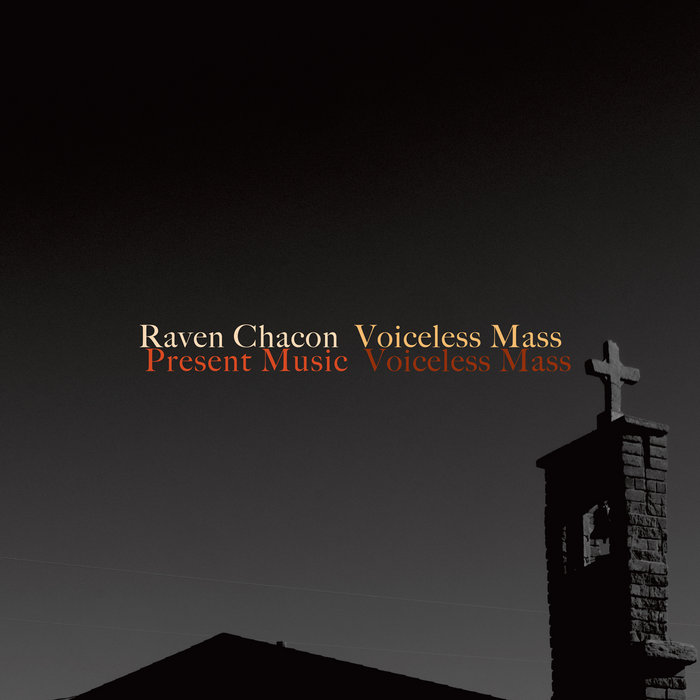

Voiceless Mass, recorded by Milwaukee-based ensemble Present Music, presents three of Chacon’s chamber works that each offer a different lens into his use of sound and silence, showcasing how listening extends beyond pitch. At the centre is the debut recording of Chacon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning composition, ‘Voiceless Mass’, which considers the history of and access to gathering spaces and the land on which they sit. Written to be performed inside of a place of worship, the piece is both a sonic and site exploration in which the church’s architecture is inseparable from the art. The album’s other two works, ‘Biyán’ and ‘Owl Songs’, take on the shapeshifting nature of sound and silence, highlighting the patience and subtle evolution of Chacon’s music.

Both ‘Biyán’ and ‘Owl Songs’ emphasize the timbral aspect of Chacon’s practice, composed of unraveling and unruly notes that flicker and fade away. ‘Biyán’, a meditation on the use of singing during Navajo ceremonies, unfolds across a series of repetitions. Each section of the piece offers a few different timbres to play with – chirps and trills, resonant hums, airy wisps, squealing textural grit – tangling and untangling them. Similarly, ‘Owl Song’ cycles through timbres, most notably those made by the human voice (a part sung by Ariadne Greif), which swings from the smallest hiss to a stunted scream. Within these pieces lie significant rests, where notes may echo or disappear, revealing as much in the chaos as in the stillness.

Recording ‘Voiceless Mass’ offers a new perspective into both the physical and metaphorical aspects of this piece. The work is about communing with a place. Players are situated around the room in conversation with each other, the room and the audience. But the organ has always been at the heart. It is the body of the church, symbolising and projecting the resonance of the space and the history it holds. On recording, the organ emerges with prominence. When it enters, it hums with ghostly resonance, haunting the piece’s severed phrases with whole, rounded notes. Though the physicality of being in the room is removed, it still feels present, an invisible driving force. In place, in time, in sound and in silence, there is still so much left to hear.