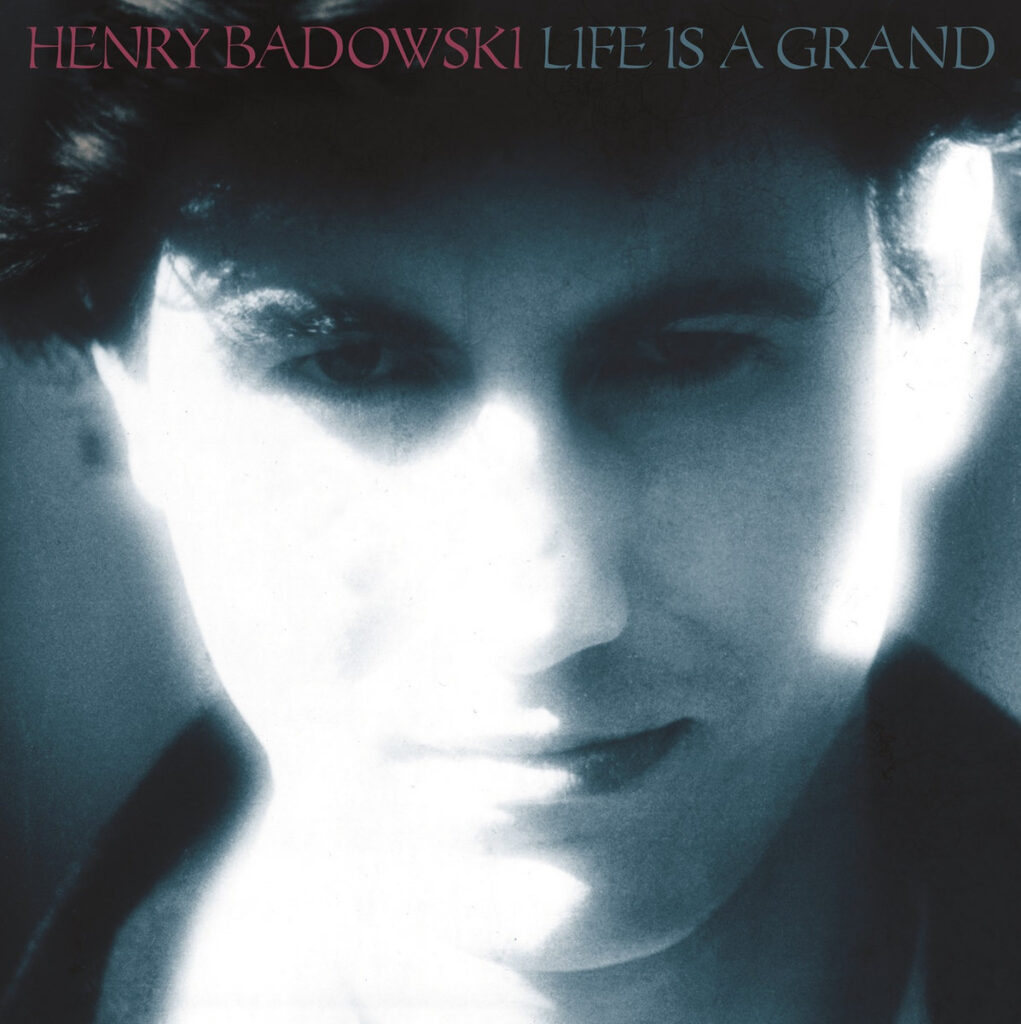

“Even a stopped clock gives the right time twice a day”, maintains Paul McGann’s character near the start of Withnail And I. He plays Marwood – the ‘I’ of the title – in a drunken and druggy but decidedly unpsychedelic cinematic glimpse into the late 1960s. The film initially flopped in cinemas at the height of 1980s yuppiedom, only to find cult adoration (and over quotation) via subsequent release on video. Everything has its right time in the end. And so it is with Henry Badowski’s one and only album Life Is A Grand, which is finally getting the reissue it justly deserves after all but disappearing, along with its creator, to near complete indifference following its release in 1981. Indeed Badowski himself seems more like a creature of the romantic 1960s than the hard-edged 1980s, the missing in action musical genius who burnt ever so brightly but briefly and left the stage never to be seen again. Novels might be written about him, why he stopped, and what on earth he’s been up to for the last forty-something years. Here’s hoping anyway, for Life Is A Grand is one of the great lost albums of the 1980s and one that almost no one has heard of. Which in itself is quite an achievement given the degree to which almost every last seam of coal black vinyl has been mined to near exhaustion by crate diggers and streamers.

Yet in the few short hectic years leading up to its release Badowski was a sort of punk Zelig. Alongside Chiswick school mate and guitarist James Stevenson, he was a member of Gene October’s Chelsea and appeared in Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee. He played keyboards for Wreckless Eric and joined Mark Perry of Sniffin’ Glue’s post Alternative TV band, The Good Missionaries. Replacing Lemmy on bass in The Doomed, a short-lived offshoot of The Damned, Badowski also sang in Captain Sensible’s no-less fleeting musical side hustle, King. This group recorded a version of ‘Anti-Pope’ in a session for John Peel, the song reprised a year later by a reformed Damned on their Machine Gun Etiquette album.

In his recent Baker’s Dozen for The Quietus, Sensible tagged his former bandmate, alongside himself, Julian Cope, TV Personality Dan Treacy and Robyn Hitchcock as the ’Syd Barrett heads’ of the 1980s. Perhaps only Badowski accomplished the most Syd-like act of all them by withdrawing almost entirely from public view.

Musically, however, Barrett is all over Life Is A Grand but arguably more as its guiding spirit than possessive demon, Badowski channelling in his own way the fallen Pink Floyd leader’s aptitude for surrealist word play and punning rhymes on the songs like ‘My Face’, where lyrics about about wanting to hang his mug on a wall “beside yours in the hall” are delivered in same clear English tones that Syd sang about riding bikes with bells on to make them look good. The glorious ‘Baby, Sign Here With Me’, upholstered by the brooding pulse of a keyboard fed through a tremolo, and with a slashing, descending guitar line faintly reminiscent of Magazine’s ‘Shot By Both Sides’, meanwhile, suggested romance might be sealed over a legal document and sustained on “cups of tea”.

Elsewhere the early 1970s output of Barrett’s friend and UFO contemporary Kevin Ayers, and circa Bananamour, often seems more apposite a reference. Particularly on the glistening ‘Swimming With The Fish In The Sea’, all woozy synths and shimmering guitar, or ‘Anywhere Else’, with its piercing two-note riff and somewhat prophetic lines, sung in an Ayers-ian growling baritone, about how he “could throw it all away”. The post-Roxy but pre-ambient Brian Eno, Can, and Neu! are other points of influence, especially in terms of the album’s texture of skittish drum machines, washed-out keys, seesaw guitars and honking saxophones on the likes of ‘Silver Trees’, and the propulsive elektronische pop of ‘This Was Meant To Be’, released as a single, perhaps tellingly, only in Germany.

Like David Bowie and another multi-instrumentalist, the saxophone was Badowski’s first love and Roxy’s Andy McKay a formative musical hero; ‘The Numberer’, the sax-laden and VCS3 heavy instrumental b-side to ‘Virginia Plain’, long cited as a favourite track, and each side of Life Is A Grand itself ends in instrumentals, most plaintively in the concluding track ‘Rampant’, with a piano line that sounds like Barrett’s pet mouse Gerald scampering down a keyboard.

Arguably Badowski was at his most-Barrett on his debut (and non-album ) single, ‘Making Love With My Wife’ – a wryly comic ode to marital sex driven by a 60s organ refrain, mirrored in the chorus melody and delivered almost deadpan by the unmarried musician, and a rinky-dink drum machine that clicks along like a primed timebomb. Yet it was this track that subsequently appeared rather incongruously – perhaps largely on the basis of that drum machine – on Machines, a compilation of none-more Cyberman-cometh synth pop featuring the likes of Fad Gadget, Gary Numan and John Foxx issued by Virgin Records in 1981.

No-one hearing Henry Badowski at this juncture would likely mistake him for say, Duran Duran. Yet his use of electronic instruments and a common love of Roxy Music et al was enough at the time to see him lumped in with the more vaultingly futuristic and frilly shirted. It was probably to Life Is A Grand’s further detriment, therefore, that the album accordingly came swathed in the voguish trappings of New Romanticism. Its sleeve art was choreographed by Stephen Lavers from the then modish society fashion magazine Ritz, and Badowski was dispatched to Levens Hall, a stately pile in the Lake District in the Burlington Club clobber of white-tie and tails, hired from costumiers Bermans & Nathans, for an early morning photoshoot involving topiary and a smoke machine. All very 1981, the year of Ultravox’s ‘Vienna’, Brideshead Revisited on the telly and the Royal Wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer, obviously. But alas not of Henry Badowski. The album sank without trace and he spent, by his own admission, “the rest of the 1980s getting shitfaced”.

There were blink-and-you’ll-miss-him turns playing keyboards with The Damned when they performed their hit ‘Eloise’ on The Tube and a co-writing credit on a Captain Sensible album track, ‘The Coward Of Treason Cove’, but not much else. A job at the BBC archives seemingly occupied him for several years until he took early retirement and began to repair and sell vintage and analogue musical gear, a line that seems entirely apt to the reemergence of his album. Its sound so much the product of kit once deemed only fit for the dustbin with the onset of the digital age but highly desirable these days. On ‘Henry’s In Love’, the album’s catchiest track and a lost new wave-y pop gem replete with girl-on-a-payphone outro, Badowski sang of knowing that when a certain thing went missing it would “reappear at some remote and unpredictable time”. For Life Is A Grand, missing in action for some 44 years, that time is hopefully now.