“Today kids get an instrument and see what they can do with it. Then they look around and start to copy, which is okay to start [with]. We were in the position that we didn’t have anyone to copy. We started from scratch.”

Edgar Froese – Totally Wired, 1986

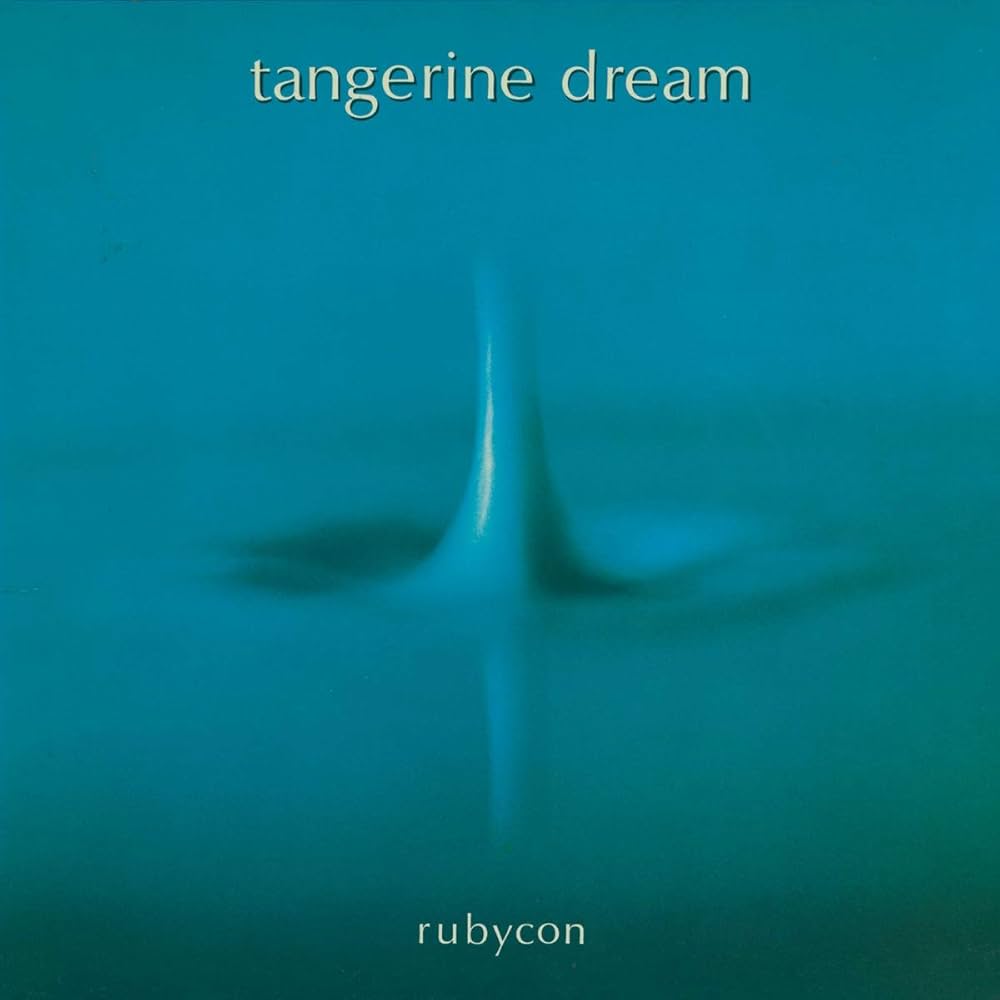

Fifty years after Rubycon was first released in March 1975, Tangerine Dream’s sixth studio album sounds like an alternative future filled with possibilities. Coming just four months after Kraftwerk’s Autobahn, its sweeping sonic brushstrokes are more progressive and evolved than that minimalist classic, a dynamic and multi-textured canvas upon which is rendered an understated masterpiece. It definitely proved to be a step up from their previous album Phaedra too, but in the context of how classic albums are viewed retrospectively, it has become the poorer cousin of the pair.

Phaedra has recently undergone the 50th anniversary treatment with a celebratory boxset that includes five CDs and a Blu-ray including the inevitable Steven Wilson mix, and quite right too given the album’s importance to the story of electronic music. Nevertheless, pound for pound, Rubycon is the superior album of the pair. Where Phaedra initiates, Rubycon augments and improves. As we’ll see, the process of refinement in pop music is rarely held in the same esteem as the inceptionary idea. Rubycon has inevitably come to be dismissed with that phrase popular with music critics “more of the same” even if that only tells half the story.

But first, some context. It’s impossible to overstate just how otherworldly Tangerine Dream would have sounded when John Peel proclaimed Atem his favourite album of 1973. When Peel introduced the band at the Rainbow Theatre the following year, he admitted the honour was as great on a personal level as the time he presented Captain Beefheart at Middle Earth in Covent Garden in January 1968. Always ahead of the curve, it was chiefly Peel’s patronage that alerted Virgin Records to the Berlin trio’s kosmische charms. Furthermore, Tangerine Dream reaching no.15 in the UK album charts with Phaedra was a vindication for him too, after he’d received a number of letters helpfully pointing out the error of his ways in giving the Germans airtime. Like the Impressionists before them, Tangerine Dream would become victims of their own success, making radical art that has subsequently become chocolate box-y in people’s perceptions.

From 1972’s Zeit forwards, the instruments of rock & roll and schlager were replaced almost entirely with synths, as the group settled on the classic lineup of Edgar Froese, Christopher Franke and Peter Baumann. By 1974, the group were appearing on stages across Europe and Australia with VCS3s, Moogs and Mellotrons. They were beckoning in the future while also flying by the seat of their hosen, surreptitiously tuning synthesisers on stage and praying for euphony once these temperamental analogue beasts were unleashed through the speakers. Technology was changing quickly, and Tangerine Dream were undoubtedly at the vanguard, though there was still plenty that could go wrong when performing live.

‘Phaedra’, the title track of the 1974 album, famously begins and ends with a synthesiser spiralling out of tune, a cosmic unravelling that would have startled the ears of record buyers more attuned to Elton John or Lynyrd Skynyrd. There was more sonic ground to be broken too with the use of sequencers throughout the rest of the album. The group had tested the sequencer once before, on the demo track ‘Astral Voyager’ that got them signed to Virgin (it would remain unreleased until Green Deserts in 1985). Repetitive basslines can be duplicated with relative ease on any modern digital audio workstation, but Phaedra largely introduced this way of building and layering songs to the world at large, the very foundation of modern electronic pop courtesy of Christophe Franke and his Moog 960 Sequential Controller.

Wendy Carlos had dabbled on Switched-On Bach, and the story of Raymond Scott’s Circle Machine remains one of the great untold tales of musical innovation, though it was really the Tangs that popularised this way of working, influencing artists like Klaus Schulze and Keith Emerson in the process. Even Hollywood succumbed when William Friedkin employed them for the soundtrack of The Sorcerer in 1977. Their sound would soon become ubiquitous where film soundtracks were concerned, the synths of Tangerine Dream becoming as synonymous with cinema as the strings of Bernard Herrmann. The best part for studios was that the hiring of longhairs with synthesisers was a lot cheaper than booking an orchestra.

Rubycon feels like an epic soundtrack to a great lost film then, though on its release it stood alone without visuals, at least for those fans who weren’t in possession of psychotropics stimulating mind-altering scenes behind their eyelids. Listening to it today, it’s easy to close your eyes and imagine yourself travelling in outer space or making an inward journey of the soul. As well as soundtrack music, Tangerine Dream were seen as key purveyors in the New Age movement of the time. It’s a genre term that’s used pejoratively now where its hipper ambient relative gets a free pass. There’s certainly an earnestness to Tangerine Dream’s music that has sometimes left them open to ridicule, though “new age” feels misleading where Rubycon is concerned.

It’s an album far more challenging than the wallpaper music that might accompany a deep soak with healing candles and Himalayan crystal bath salts. Aside from a resonant gong at the outset of ‘Rubycon, Part 2’, it’s never an easy listen. Instead we’re introduced to the eeriest of atmospheres, with a Ligetian dissonance running through both seventeen minute tracks, often imbuing the listener with a sense of foreboding. Uncanny human voices made with the Mellotron transport us to some place else entirely, perhaps beyond the curtain of the underworld where we can look back at our own frightened reflections.

‘Rubycon, Part I’ goes slightly easier on the listener with passages that are redolent of Pink Floyd, but things are often spiced up with playful interjections that nod to Ravel and Tchaikovsky. Rubycon’s soundscapes are streams of such sonic abundance that you never feel like you’re stepping into the same river twice, once you’ve lowered the stylus onto the groove. It’s only later down the line that Tangerine Dream painted themselves into a corner, soundtracking lame US teen comedies and short-lived TV shows. On Rubycon, they can do no wrong. Even the simple album artwork with the cover shot set up and photographed by Froese’s wife Monique featuring a turquoise drop hitting some liquid feels like everything falling (literally) into place. The record may well be Tangerine Dream’s crowning achievement, and yet Rubycon is forever seen as the follow-up to a more important work. Where classic albums are concerned, importance is too often confused with quality.

A case in point is Amnesiac by Radiohead, an album that received mixed reviews upon its release in 2001, with Kid A regarded as the superior of the two largely driven by its originality. Time has been kind to Amnesiac, an album that’s more layered, emotive and epic than its predecessor, though it still remains largely misunderstood beyond the fanbase. XL Recordings cannily got over this problem in 2021 when it reissued both albums together under the clumsy, disjointed portmanteau Kid A Mnesiac, a cunning way to repackage a classic album and its less loved successor for fifty quid, throwing in a bonus disc (Kid Amnesiae) to make it look like the deal of the century.

To challenge the orthodoxy by suggesting that Speaking In Tongues has stronger tunes than Remain In Light or that Live Evil is more listenable than Bitches Brew is to risk accusations of contrarianism. While it would be disingenuous of me to suggest that “Heroes” trumps Low, an argument could be made for Bowie’s realisation of a vision that stutters and sometimes falters on the first Berlin album, even if that stuttering exposé of human frailty is part of what makes it so special. Perhaps in an age where we feel the album needs protecting from the tyranny of the playlist, we need to think more about protecting artistic trajectories that spread beyond isolated albums, rather than conforming to the rockist mindset and the heritage machinery that this article is undoubtedly a part of.

What is interesting is that where critics have always decried “more of the same”, record companies secretly love it, especially following a successful campaign and millions of records sold. Indeed, the obsession with the shock of the new is still very much a preoccupation of music writers to this day, even at a time when new genres no longer fall from trees, not that most critics can see the wood from the trees anyway.