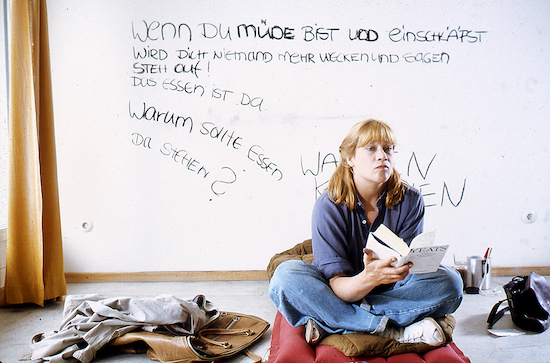

Die Bleierne Zeit, 1981

During the length of our conversation Margarethe Von Trotta says the word truth over a dozen times. Whether she’s searching for it, reaching out to it, or closing in on it, Von Trotta makes it perfectly clear that it’s her mission to privilege the truth of her subjects.

With an acute sensitivity to the plight of women and a rhythm unique to her own it’s easy to see why she’s been labelled as “one of the most important feminist filmmakers in the world”. But it’s a title Von Trotta doesn’t lean too strongly into, fearing the artistic ‘ghetto’ such a title would leave her in. To be labelled as someone who simply makes “women’s films” implies a rigid definition of what a woman is and what their truth may be.

Von Trotta was born in Berlin in the early 40s. She was raised by her mother, Elizabeth Von Trotta, with occasional visits from her father Alfred Roloff, who was a painter. She attended a commercial school before deciding to go on and study Art.

It was a while before Von Trotta committed herself to the director’s chair, finding herself as an actress working with The New German cinema heavyweight Rainer Werner Fassbinder initially. In Fassbinder’s Gods of the Plague, Von Trotta streaks her performance with water-colour-like delicacy. Von Trotta’s performance is the picture’s strongest and subtlest assets, becoming the physical embodiment of Fassbinder’s dramaturgical questions about identity and external representations.

It seems like Von Trotta’s hunt for truth and identity never strayed too far from her artistic output. It was on a trip to Paris where the idea of directing came into full focus. Becoming enamoured by the works of Ingmar Bergman and Alfred Hitchcock, she began to value the culture of cinema over its commerce. It was Bergman’s The Seventh Seal , however, that resonated with her most deeply, “I was inspired by the way he focused on the souls of his characters. He had a way of closing in on the female face…to find their truth.”

Das zweite Erwachen der Christa Klages, 1978

Since then Von Trotta’s small yet muscular filmography has frequently interrogated the intersection of gendered expressions and personal truths, entangling them in an intricate temporal yarn. “In cinema, we have a ring-fenced way of seeing women” says Von Trotta “You’re either the humble woman, the mother, the whatever, I do not restrict myself to that – I don’t search for a technical way of creating ‘woman’.” To Von Trotta, the female gaze isn’t something that can be constructed formally, it is not a laboured aesthetic but an ecstatic, historic truth. This truth, whether political or personal (or, more commonly, an interrogation of both) bleeds into all of Von Trotta’s films.

“Since the Greek ages, Men have been seen as heroes…”Von Trotta says, launching directly into the historical bias towards the masculine. She’s right, pointing out the word ‘hero’ has yet to be eroded by the feminine, still portrayed as a cultural gift of idealised masculinity. The rugged pursuit of the truth (usually with a female reward) is never comprised nor challenged because of their gender. Von Trotta shows this to be a dazzling myth, her works performing a cultural coup on the gendered pursuit of truth. Across her body of work both masculinity and history are roadblocks to the political and personal expression of her chosen female subjects.

She most deftly canonises her thematic preoccupations in The German Sisters. Based on a true story but never flaunting sensationalist credentials, The German Sisters concerns itself with the search for feminine political expression fighting whilst against the tide of their own gender. In the film, both Marianne and Juliane are politically active feminists. Julianne, the designated intellect, uses her words, working as an editor for a populist feminist publication. Whilst Marianne uses force, through politically motivated attacks, to push her agenda.

Displaying her admiration for Bergman, Von Trotta deals in an economy of long takes, occasionally disrupting the narrative flow with a close-up of the female face, halting the camera’s search for the truth. Both sisters’ political expressions are held hostage by the male expectations of them as women. Julianne is a failure of as a feminist for choosing the pen over the sword. The same fate befalls Marianne for displaying no interest in her societally provided role as a mother. Their desperate search for identity and truth consistently marred in cruel gender politics.

A kindred, but perhaps more conspicuous version of this truth is apparent in Rosa Luxemburg. Von Trotta’s Luxemburg (Barbara Sukowa) isn’t a schoolteacher interpretation, sharply veering away from typical biopic textures. Von Trotta instead opts for a more rewarding character study, stringing together personal and political scenes like pearls on a necklace. Von Trotta directs scenes of Luxemburg’s political rallies like quiet symphonies using minimal formalism to maximum affect: eye level camera, moderate long takes and unfussy editing. The strategy pays off in spades. Barbara Sukowa becomes the beating heart of almost every frame she’s in. This makes tension between Von Trotta’s formalism and her narrative treatment feel all more cruel. Through out the film, Luxemburg spits back at the general leadership’s dogma, refusing to compromise in her approach to politics. Von Trotta’s restrained, parred down style making Luxemburg’s muzzling at the hands of senior leadership all the more sobering.

However, it’s Barbara Sukowa skin-prickling performance that certified to the believability of Rosa Luxembourg, transforming her into something more than a political symbol. “As a director, actors must feel like they can risk everything…you must expose them,” Von Trotta says. There’s an exposing of Luxemburg here that never feels exploitive, Sukowa delivering superhuman levels of sensitivity and empathy for her character, elevating her to a status beyond woman-in-politics.

Rosa Luxembourg, 1986

Even in her debut film, The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, the quiet confidence with actors that bolsters Von Trotta as an excellent humanist are firing on all cylinders. The icy stylings of her co-director, Volker Schlöndorff, take second fiddle to Von Trotta’s undeniable grace as an actor’s director. “Being an actor before a director taught me how expose them… and how to pull them back,” Von Trotta mused over the phone.

The most thematically didactic of her works, The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum is nonetheless a stunningly considered assault on the media’s search for ‘truth’. Ranging from personal defamation to physical assault, the media in Von Trotta’s film uses every tool in its grim arsenal to suppress and distort Katharina Blum’s voice. So it’s surprising the grace with which Von Trotta directs Angela Winkler’x physical performance. Marked by equal parts placidity and rage, Winkler delivers her lines like she’s spitting poison. But Von Trotta is careful with Winkler, pushing her to deliver a performance of a woman victimised but never to play the victim.

When the police raid her flat, Katharina Blum, gently leaning against her breakfast table answers degrading police questions with a perfectly match smirk. Her performance takes the film to jittery new levels of tension, directly confrontational one moment and maliciously elliptical the next. But this deviant, complex piece of screen acting mimics the obscuring of truth. It seems Blum realises soon that the truth is never a fixed thing, but something to be ruthlessly controlled and casually weaponised.

It’s perhaps Von Trotta’s search for what the ‘truth’ is that gives her films such heat and energy. Von Trotta peels back the layers of her subject, extracting their truth with scalpel precision. Von Trotta’s cinematic representations work so effectively because she exposes the way gender conceals rather than clarifies. Unmoored by the temporal contexts of her films and the women she presents, Margarethe Von Trotta has managed to free herself and her subjects from the burden of historical representation in her movies. Throughout her films, Von Trotta surveys the historical territory with a clear vision, with an unmistakeable sense of compassion for her characters and the admiration for their truth. She fluently challenges the idea that the truth, and the journey to it, is ever clear.

The German Sisters by Margarethe Von Trotta screens at selected UK cinemas this week. Lost Honor Of Katharina Blum is available now on Blu-Ray