You might find hexed! bewitching, in fact we reckon if you have open ears you surely will. But Aya’s primary motivation was not to beglamour you, regardless of how spellbound you may feel after a few days in its company. The album – in a psychic sense – is like catching a glimpse of Hex Enduction Hour in a black mirror. These cross generational comparisons can provoke contempt from both equally offended parties, but this a structural juxtaposition that offers notable load-bearing qualities. Both are sliced through with a hyperdense world-inventing/ world-inverting lyricism that one could spend very many hours unpicking; both throb and crackle with occult intensity; and, despite some perceived spikiness, both are vivacious, irrepressible, even. But, in magical terms, The Fall’s scabrous 1982 masterpiece was presented as a (corporate) ritual invoked to end a several-year-long run of bad luck for the band themselves while Aya’s second album for Hyperdub actually celebrates the lifting of a (corporeal) curse from herself. But what was this hex and was it self-inflicted? Well, there’s a can of worms we’ll need to open if we’re to proceed. But first, there are some literal, if highly symbolic, earthworms for us to deal with.

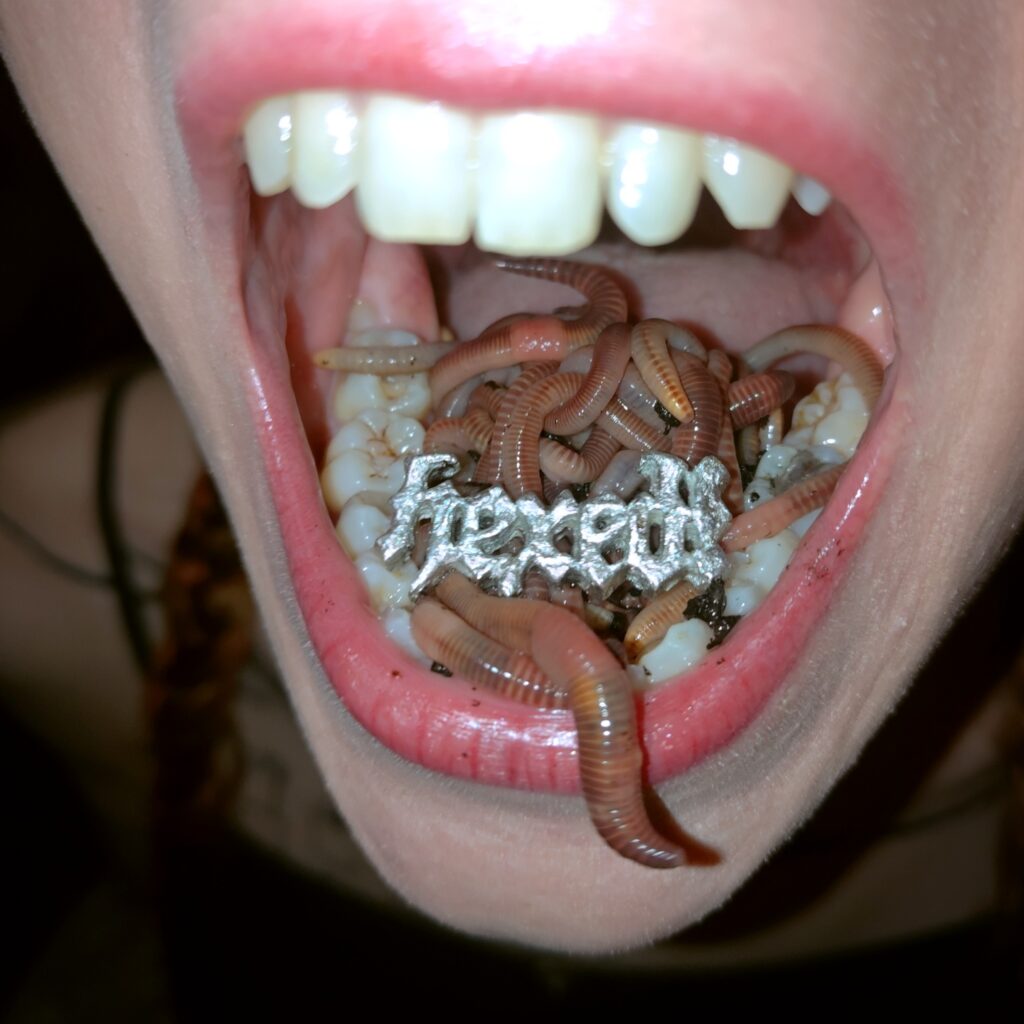

The cover art features a mouth stretched wide open, housing a clew of earthworms. The clythelus and segments of one jaunty, inquisitive creature, slinking out chinwards, juxtapose deliciously with the stretched, near segmented tubercles of the lower human lip; the worm looks like a salacious, gangrenous tongue or the bisecting tail of a capital letter Q in a freaky, blinged-up, photobook grimoire. Yes, she confirms, that is her mouth and, yes, they are real live worms. Which immediately creates another tangled, writhing clew; a knot of follow up questions.

Aya is speaking to me today from her flat, in residential Lewisham in South London, enjoying what she refers to as “the quiet life”. Nearby she has “a Budgens which fancies itself a Whole Foods”, which is “ideal” as she points out sagely. This quotidian quietude is lifestyle and outlook related, but doesn’t really relate to the grain or intensity of her new music. The album shows that her sound has effloresced in multiple directions and dimensions, taking on many new textures since we last spoke to her, on the release of Im Hole back in 2021.

There are obviously many steps between idea and execution, not to mention plentiful off ramps betwixt, when it comes to stuffing worms in your mouth, so she unpacks the process. There was a wish to follow on from the cover of Im Hole – which depicts her hand offering the listener something indistinct – with another body part, and because of a growing emphasis on her lyricism, a shot of her mouth became logical. However she understood implicitly that this alone wasn’t enough: “There had to be something uncanny or terrifying happening in there.”

But why worms? “I just think there’s something about these things that are burrowing through the earth, absorbing all of this waste and pooping out nutrients. They are hideous beings – really, really nasty to look at – but they fulfill this amazing function.”

The worms were sourced from a pet shop in Lewisham, saving them from ending up as lunch for a local lizard, and on the day of the shoot the actual process of having a gob full of terrestrial invertebrates ended up being less stressful than you might imagine: “They don’t taste of anything. Although, as you can see in the photograph, my tongue is pulled back and they’re just kind of sitting there.”

Were they lively? “Er, they weren’t too bad. It just felt like someone had dropped like a small bowl of soba noodles into my mouth. And then they started moving. And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a little strange.’ And then there was one which tried to make its way back towards my throat and that was a hard, ‘No.’”

The set up had to be repeated six times to get the right shot of mouth with worms topped by a bejewelled brooch containing the hexed! title (a one-off, custom made charm by artist Rebecca Irvin). As for ignoring the temptation of off ramps, Aya had made a point of telling numerous pals she was going ahead with the photo until she felt she had to – which is a kind of rough and ready magical practice in itself. Her advice for Quietus readers who want to do likewise? Have a good crew of people on standby: “My friend Freyja, who has done wardrobe and styling for me previously, turned out to be an expert worm wrangler.” Also, that person needs to have a very clear worm extraction plan: “A large bucket and a bottle of Listerine was how we got through it.”

The humble and ancient earthworm is as symbolically rich as the humus it helps produce; from Old Testament symbol of guilt, to early Celtic Christian representation of displaced pagan faiths, to more modern ideas of the cycle of life and natalism. Aya is still working out, not what they mean to her, but how much it is wise for her to say; the subject nature of the album is sensitive and something that is still relatively raw. She’s working out in real time how much she wants to say: “Initially there was this idea of them being mindless soil dwellers. And this is about my expulsion of worms, like I’m about to vomit them up as I scream. But there is another level where they fulfil a really important part of the ecosystem, which is easy to forget given that they’re such horrible little fuckers.”

Another pause, and then: “When it comes to trauma, I think you can see both sides of an event. You come around on the other side of something and then understand it as necessary for creating the person who you are, I guess.”

The curse lifted is one of substance dependency, the hex, one of harmful and continual drink and stimulant abuse. The release of hexed! will coincide with Aya – lowkey, quiet life – celebrating seven months clean and dry.

She explains: “The album is a product of looking back through a bunch of the most difficult experiences of my life, and trying to come to terms with them. It’s been an incredibly painful record to make. And it’s taken me this long to make it, for exactly that reason, because a lot of it has involved going back into the mental state I was in during those experiences. I was trying to re-inhabit them.”

The new album covers a lot of ground. ‘Off To The ESSO’ might gallop into view like a panelbeating 175bpm gabber techno thumper but it’s more akin to nerve-shredding hyperpop than anything she’s done before. ‘The Names Of Faggot Chav Boys’ – a song delivered with the “utmost sincere respect” for its unnamed titular protagonists – is a post-six-day-party panic attack unfolding while Autechre’s ‘Skeng’ remix and Bela’s Noise And Cries play somewhere simultaneously in the background. Across this album, which is written, produced and sung by herself, there is a tendency for Aya to process her vocals in a continuously shifting manner (to represent a rapidly fluctuating state of mind perhaps) and this does initially kick dirt over the fact that these tracks are now more than ever like traditional songs compared to much of what she’s done before. And by that I do mean that they have verses, choruses, and even the occasional post club middle eight. It becomes easier to hear on the (absence of) love song ‘Peach’, which leans more into the screamo mode of contrasting ‘sweet’ with ‘harsh’ vocals. The ‘songiness’ of the album is at its most apparent, perhaps, on the confessional ‘Droplets’, which even then doesn’t exactly sound like Fiona Apple. (More, to these ears at least, like creating an odd zone somewhere in the middle of Jules Reidy, Jenny Hval, Shackleton and the clanking Švankmajer rhythms of Tom Waits’ Mule Variations.) Elsewhere deathcore (‘Navel Gazer’) and blackened gaze (‘Time At the Bar’) add more to this complex stew.

While it might seem like the inclusion of elements relating to screamo, deathcore, digital hardcore and black metal consist of new ground for her to cover, it’s something of a return to core sonic values: “From the age of 11, when I was first starting to form my own kind of musical taste, there were two strands for me. On one hand I was into Slipknot and System of a Down, and on the other I was into Aphex Twin and Autechre. If you take those two things and sprinkle a bit of transness on top you get this record.”

I do whatever passes personally for raising one eyebrow, so she adds: “Well, later, I was into deathcore, Suicide Silence, a lot of Joey Sturgis-produced music, Job For A Cowboy. And then it was emoviolence and ‘real’ screamo like Pg. 99.” And after a break of several years since her mid-teen skating days, she admits it’s an area she’s becoming interested in once more.

Without getting too deep into the process of studying the album track by track – there will be a review of hexed! Published on tQ later this month – she says something that immediately leaps out as being a key for understanding how the album sounds so different without being too jarring, yet still standing on something of a continuum: “Previously, I wanted to use all of the noises that everyone else was using, but to create my own structures. But this time I thought, ‘What if we flip it? What if we use normal structures but create novel sounds? To use that as a compositional strategy. And I think it’s made the music, despite seeming quite strange on the surface of it, much more accessible.”

Referencing my initial, simplistic idea from last year that this voyaging into much “darker”, “heavier” and “hectic” waters might necessitate cause for concern, she adds: “The music is much darker than it’s been before and much more aggressive, and also maybe manic in a way that it hasn’t been before, but, actually, that’s a reflection of how well I’m doing. The whole reason I’m able to make music like this is because I’m more present with myself.”

She outlines the change precisely: “I haven’t drank anything or taken a drug, coming on for six months. There have been no mind-altering substances going on here. I am sharp and in reality.”

She lists an ingrained tendency to get heavily into things for months at a time, and says this tendency applied to her use of drugs as well. Drinking alcohol was not a problem in and of itself when she gave up but she had previously had a dependent relationship with it and it was a clear trigger, so she stopped drinking as well. She adds: “I could no longer deal with the emotional rollercoaster that I was living on because of it. With touring and trying to do this record, it was like, ‘OK, let’s wipe the slate clean. We’re done.’”

At no point does she meet any of the cliches about people being in the evangelical early stages of recovery, but then, in my experience, people rarely do. She speaks about ketamine in a nuanced, if somewhat self-effacing manner: “My last album is explicitly about doing ket. Ketamine was a heavy part of my personality then. My view of myself was as someone who ‘understood’ ketamine, who had a ‘different and otherworldly’ relationship with it because it showed me previously unrevealed sides of queerness and it offered communication with the sublime.

“And on one hand, sure, that’s all true, but maybe I don’t need to be doing it four times a week, or worse. If you’re smashing ket every night, it’s just not a sustainable position to be in. And I think the distance it put between me and the people around me was not ideal.”

She laughs in conclusion: “With things like ketamine and cocaine, it had spiralled out of control. I would wake up the next day and eventually piece together this memory of it being 4am and me listening to ‘Hide And Seek’ by Imogen Heap three times in a row, crying on the kitchen floor. I was like, ‘This is embarrassing, man. I’m not doing this shit any more. I’m too good for this!’”

A real “clincher” for her staying sober has been getting a diagnosis for ADHD and access to the medication that she has likely needed for a long time. She frets slightly about recent shortages – she mentions something that will make many people reading this nod in recognition, that otherwise she is simply dependent on pounding coffee to get any kind of focus-heavy admin work done – and admits that the days she has had to do without have been “a real test”, but for the most part it has changed her life for the better.

Speaking about the idea of witchcraft that permeates the album, Aya states that a key factor was several years ago reading Caliban And The Witch by Silvia Federici – outlining the radical idea that the medieval witch hunts that raged across Europe and colonial America, served to restructure the family and take ever more power from women, which was necessary for capitalism to grow: “The book was just whirring away in the background. But it possibly started me travelling along a road towards having a more magical or alchemical outlook on life, even though I was always very much a ‘rational skeptic’ about the idea of magic.”

She is aware that the idea of the witch itself is in an appropriate state of flux, and transforms as time goes on: “It concerns the idea of women existing outside of the preordained structures for womanhood in the mode of the times that they’re living in; so obviously there’s a real trans allegory going on there that fits the present moment.”

The bristling opening track, ‘I Am The Pipe I Hit Myself With’ concludes with the whispered line which drips with implication: “I’ll never let myself forget/ they had me out on a witch hunt when I found myself”. And when she reveals the specific incident she is referring to, it is temporarily blindsiding: “When I was a teenager I joined a Pentecostal church in Huddersfield. I was part of that congregation for nearly two years. I was fully born again… speaking in tongues… that kind of business. Yeah, real, real scary shit.

“And that really did a number on me as I was growing into my queerness. I think part of my desire to join the church in the first place had been to find sanctuary from the messier end of this self that I was beginning to understand. Right?

“So just as I was trying to take refuge inside this structure, I ultimately ended up bumping against this thing that was emerging – this latent queerness – and they were not comfortable with it. No surprises there. I was given the option to fully closet myself or leave.”

This was a blow to the teenager who was fully committed to the church, and was at that point attending three times a week: “There was no mention of sending me off to a camp for conversion or anything like that but the vibe was very much don’t ask, don’t tell. Because I identified as bisexual at the time they were weird with me. One of the head pastors said, ‘We know that you get on well with this girl, so maybe…’ As if they were some weird fucking matchmaking service.”

That was the last straw. She left, but it was difficult as a self-described “loner kid” to give up this newfound community, not to mention the opportunity to have a “euphoric relationship” with music in an evangelical religious setting. This sense of community is something that she would proactively seek out from that point onwards, in the queer boygirl collective of Manchester and in the deconstructed techno and post club scene centred around the White Hotel in Salford. But as desperately painful as it was for her to leave the church, she does have a nuanced view of it now: “I was subject to a persecuting force, shaming degenerate behaviour, but it was only through becoming completely enmeshed in that, I was then able to reckon with who I am.”

The album ends with a transcendent transit of bliss from the threshold majesty of ‘The Petard Is My Hoister’ to the pulsing electronic blackened gaze of ‘Time At The Bar’. ‘Petard’ is one of two instrumental tracks, which give the album its occult structure. The album strides purposefully down into a hellish space, revisiting zones of addiction and dependency, firing up emotional simulacra of trauma and neurosis, reaching the lowest point directly in the middle via the ego-shattering title track, which sounds much more akin to Pan Sonic or KTL, than anything surrounding it, before heading up and out the other side, towards reintegration and literal closure. ‘The Petard Is My Hoister’, was written by Aya when she had a single image from the Pawel Pawlikowski film Ida very present in her mind – a curtain in the air representing a spirit leaving the body. The track sounds like the work of Morton Feldman if he’d grown up a first wave Gen Z laptop-wrangler hooked straight into The White Hotel scene. And then, black metal-referencing it might be, but ‘Time At The Bar’, is clearly beatific, not savagely battering.

The magnetic pull of the West Yorkshire moors is a theme she returns to time and again. When I ask if she grew up close to Marsden Moor she says, “Close enough.”

So is black metal a good fit for the landscape of your childhood? Closer to the sky, closer to the elements, closer to a state of sublimity? “Categorically, yes. The feeling of being on top of that hill and unable to see anything other than that scrub, the bracken, the sky, and that’s it. And you have the driving rain in your face? It is the perfect zone for that music.

“Someone played me some lush, beautiful, classical music inspired by the Moors and asked me if it reminded me of home and I said, ‘That is not how I see the Moors my friend.’ It is such an oppressive environment, but otherworldly. And with hexed! that’s the narrative that I’m trying to get across: that I’m letting go of this idea of an imagined future that I once fed myself on from a very young age. The aspiration to have a heteronormative life of going away to university and then coming back and starting a family. To live in a little village on the Moors. It took me years to get over this idea and it was really only over the last year that I did get over it: to realise that’s really not the life I want.

“I would love to live on the Moors, for sure. But I’m not looking to detransition and start a family. So ‘Petard Is My Hoister’ and ‘Time At The Bar’ represent the point of freedom; they are the curse of hexed! being lifted. Last orders are being called on the idea of me returning to that kind of life.”