Paris, September 8, 1926

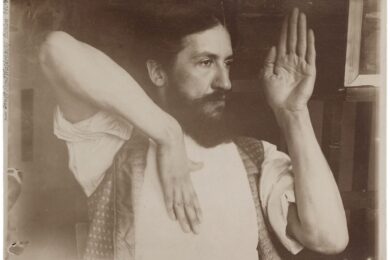

The correspondent for De Telegraaf, Amsterdam’s most widely read daily newspaper, anticipated that the studio of his country’s best-known living painter would be a cross between a laboratory and a monk’s cell. He knew that Piet Mondrian lived where he worked and was a recluse, albeit a friendly and agreeable one. Even while inhabiting one of the busiest and noisiest neighborhoods in Paris, being a regular in his chosen cafés and dance halls, and attending lots of other artists’ openings, Mondrian famously isolated himself when he repaired to his solitary lair. He kept his surroundings modest and simple, and eliminated disturbances in what he saw, in the same way that he simplified his personal life, to concentrate on his painting and writing.

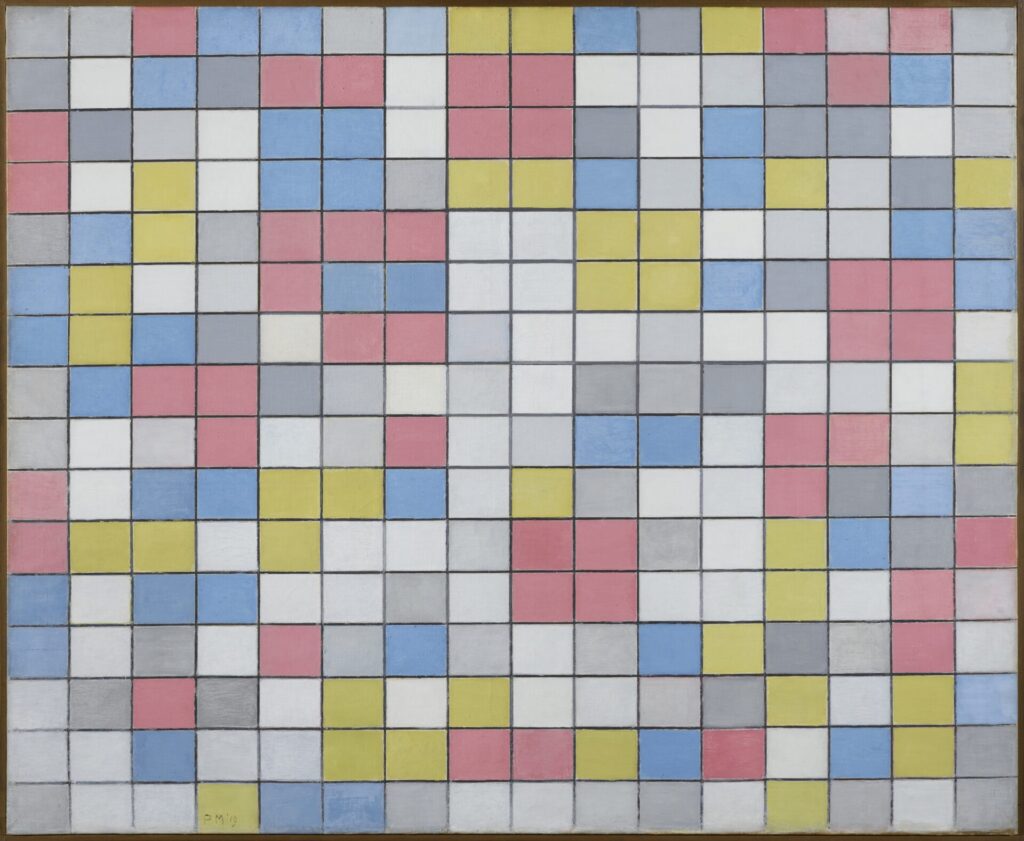

Mondrian was not averse to publicity, however. The journalist had read accounts by several other writers who had visited the artist’s studio. He already knew that it was basically a large room with high white walls on which the fifty-four-year-old abstract artist had hung small panels of vibrant primary colors that he regularly moved around. One day Mondrian would raise a yellow square by five centimeters; the following afternoon he would edge a larger blue vertical rectangle ever so slightly sideways. Each variation would alter the beat and change the rhythm of the entire space. Nothing, however, had prepared the eager journalist for the shock of these living quarters inhabited by the man who declared “Art has to be forgotten: Beauty must be realised.”

Artwork © 2024 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

The Telegraaf correspondent was struck first by “the squalid yard behind the clamour of the Gare Montparnasse” where one entered the “dingy staircase” which led to Mondrian’s door on the third floor. The sound of clanking trains arriving from the Paris suburbs or announcing their imminent departure for Bordeaux with loud whistles had now subsided. He anticipated a surprise as the door opened, but this was not the one he imagined. The writer was enjoying a refreshing calm as the hustle and bustle behind him faded and the clean-cut artist in workman’s overalls greeted him amiably. Then he entered a milieu that bowled him over. “What a contrast! No Thousand-and-One Nights here, opening up a treasure-filled cave to the poor camel driver. Instead of riches, this lonely ascetic offers a dazzling purity, causing everything to be bathed in a pristine glow.” While the journalist caught his breath after walking up the dilapidated stairs and Mondrian opened the shabby wooden door to the white cavern with its panels of bold colour vibrating from unexpected locations, the impression of sheer originality staggered him. He faced a unique combination of poetry and toughness.

The studio had a pervasive quietude, yet transmitted decisiveness and certainty. Every stick of furniture, the colours with which each panel had been painted, the few books and ashtrays and utensils, the absence of anything else, were without compromise. Other artists and designers and patrons of the epoch lived in related styles, but no one else had the rigour, the mix of finesse and roughness, the flair to make plywood more elegant than travertine. And the paintings, while as ethereal as clouds, emitted an extraordinary force. Here was power made friendly and welcoming. While clearly the products of refinement and discipline, they were playful and joyous. Their ebullience and spirituality were all the more plausible for being rooted in logic.

No one else lived like this; no one else painted like this. Many imitated his style, some of his contemporaries copied him, and in time the motifs he invented would appear on dresses and ladies’ shoes, from discount stores to haute couture, just as his name would be used to confer a certain panache on hotels and apartment buildings, but none of that was the same thing. The artist’s existence on the rue du Départ, and the art he made there, harnessed manic enthusiasm with exquisite control, both at their extremes. Most people live by half measures, or follow someone else’s ideas. Mondrian had created, in his rudimentary living quarters and bright airy workspace, a private sanctuary, suited only for its sole inhabitant. What to others would be self-denial was for him the pathway to nirvana.

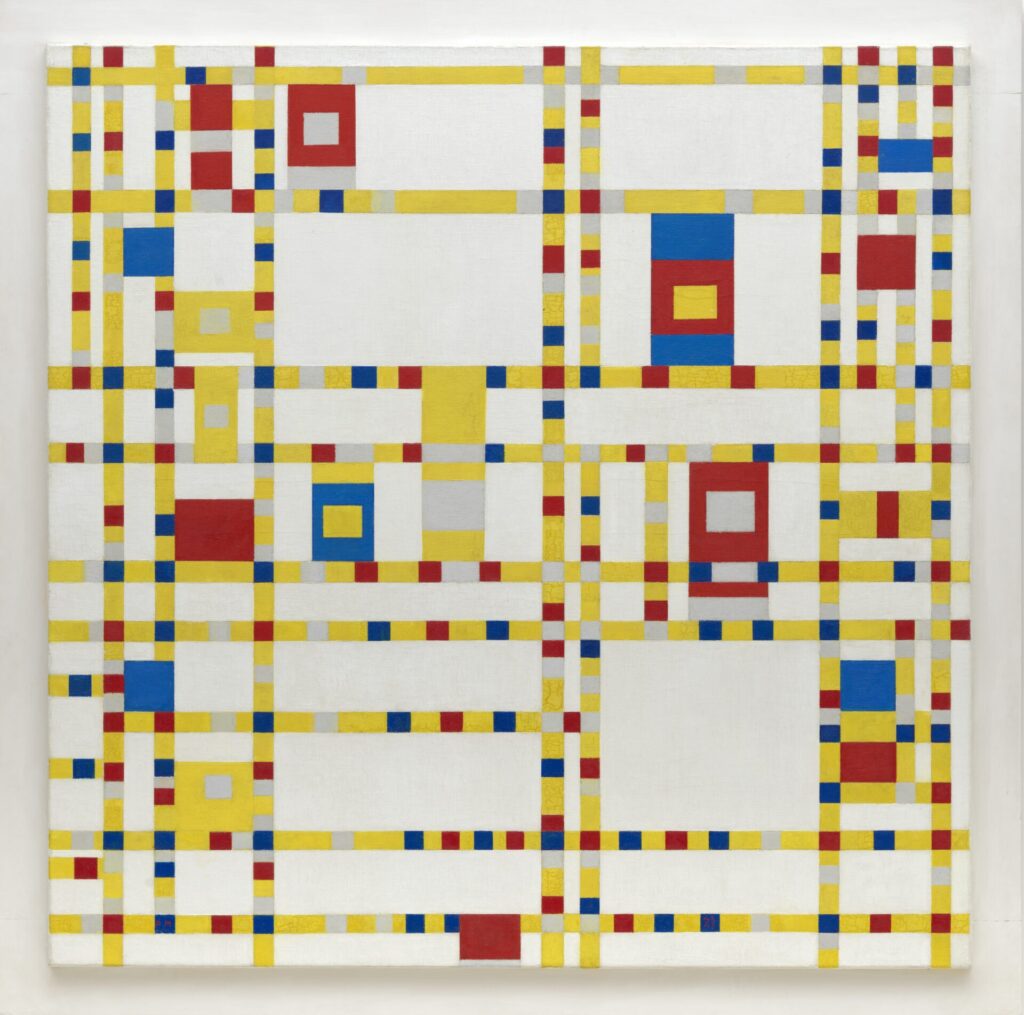

Mondrian had recently been asked to do set designs and a house interior which, like his own living space, obliterated the usual distinction between “fine art” and the total environment. With the Bauhaus flourishing in Weimar, Le Corbusier’s sparkling villas starting to proliferate around Paris, airplanes crossing the skies on a daily basis, and furniture becoming leaner in form and devoid of ornament, buildings and paintings and household objects had acquired unprecedented clarity and élan all over the map. But Mondrian’s interiors, while belonging to their era, were completely original. The compositions for the walls he put into theaters and people’s houses were austere but jocular. Their luminous backgrounds were predominantly a meticulously chosen greyish white, or two such tones that were ever so slightly different, while most viewers discerned them as being identical. They were constructed of a few black horizontal and vertical lines, as refined and carefully calculated as the components of an airplane engine but clearly handpainted, with small powerful areas of one, two, or all three primary colors.

The reds, yellows, and blues were at impeccably determined intervals from one another –creating rhythm and expressing energy and joie de vivre in a way that boggles the mind. These radically modern stage sets and living rooms have the same power as certain Romanesque church interiors and the grandest Baroque staircases. What we take in through our eyes penetrates our entire being.

Mondrian: His Life, His Art, His Quest for the Absolute by Nicholas Fox Weber is published by Knopf