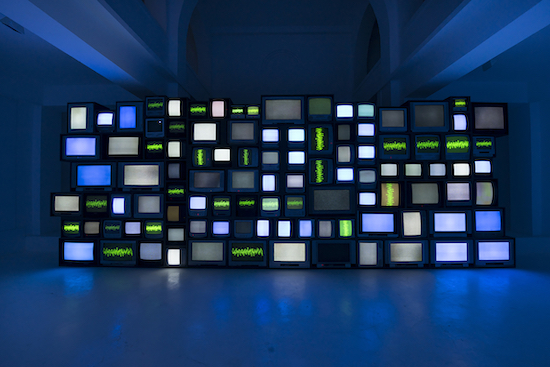

Susan Hiller, Channels, 2013, Video installation with sound, Dimensions variable © Susan Hiller Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Susan Hiller could be regarded as one of the most important conceptual artists of the twentieth century. Her work has engaged with themes and subject matters long before their perceived importance within the art world and has done so in a thought-provoking, engaging manner.

Having relocated from Florida to London towards the tail-end of the 1960s, Hiller used the nature of otherness found in such a move as an inspiration that remains present in even her most recent works. The subject of a major retrospective at Tate Britain, her work has entered the conceptual art canon as she continues to research, make, and present new work at an enviable pace.

Her work continues to ask and present relevant questions, with the recent Resounding series tackling the limits of our understanding and perception in the face of an ever expanding universe.

In researching Belshazzar’s Feast, the Writing on Your Wall [a multimedia installation from 1983-4 combining video, colour photography, drawing, sound and interior furnishings reimagined in 2015 as a ‘Campfire version’ consisting of a stack of television sets showing fire, soundtracked by Hiller’s improvised singing, media reporting paranormal sightings and familial recordings], I was reminded of a story in which a child is taken camping by his father.

He’s sat in the woods by the fire and he starts to believe he sees shapes in the flames. He tells the father and his father says that the shapes are demons, he has to stay up all night, staring into the fire with his eyes open until he fights the demons off. If he closes his eyes before this, the demons will drag him through the fire and into hell.

I thought this was interesting in relation to Belshazzar’s Feast, particularly it coming in two iterations. The way that the first was this archetypal family space pointing at the television versus the omni-directional screens in the later version seems like a representation of the way that we digest and absorb media from multiple points, the malleability of contemporary viewership.

Actually the campfire version was first shown in a somewhat different form in my show at the ICA in 1986. The original living room version refers to the real meaning of unheimlich, something repressed or unacknowledged in the home that emerges with uncanny, frightening effect. The campfire version relates to the way people like to tell stories around a campfire, frequently ghost stories – both situations can be frightening.

Your idea that we receive information from multiple points is foregrounded in the campfire version, but basically the effect on viewers is the same in both iterations. The work is set up to draw people in, to encourage empathy. You can accept the experience at face value or you can reject it, it’s up to you.

I want to say something that relates to your really horrible story about a campfire. I always like to tell this about Belshazzar’s Feast because it’s the way people sometimes misunderstand it completely. A man who always liked my work told me that he absolutely hated this piece. I asked him why and he said “you put in all those devils. Why are you making me watch all these devils?”

I said, “You are putting the devils there, not me”. But he never believed me.

Other people tell me, “I love the piece! I saw dancing dinosaurs!” They think I make animation and insert it under the fire imagery… I would like people to realise that the moving blips of light are triggering images. I want to give back that self-awareness to people. But if they insist on ignoring the fact that they’re making the images, then the work has failed.

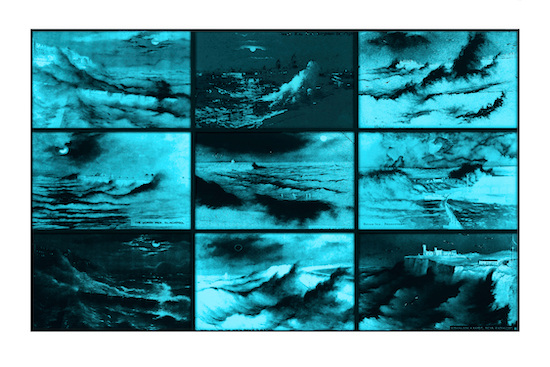

Susan Hiller, Rough Moonlit Nights (Cyan), 2016, Glicee print on Hannemuhl Photo Rag, 101.6 x 76.2 cm, 40 x 30 in © Susan Hiller Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Can it fail? If you’ve presented something that can trick a viewer in such a way that they refuse to believe they’ve even been tricked, that seems like an enormous success for revealing the power of the mind.

Well, my interest in setting up these situations is in creating a conscious awareness of how we operate. That we are simultaneously creating and perceiving the world, that the two processes are entirely related and usually simultaneous. That’s what I’m interested in.

Is that what you were saying in your later work, Psi Girls, from 1999? [A video installation depicting a series of girls and young women manipulating telekinetic abilities, with the footage lifted from films]. Psi Girls has been discussed as a kind of ode to girl power or claimed that it shows how the media misrepresents the bourgeoning sexuality of young women, putting a fear element into it.

A newspaper said that. It’s like when people ask me “Do you really believe in this?” Do I believe in colour? Why does it matter? What’s to believe? I’m an artist.

Psychokinesis is subject matter. It’s not the content of the work. Everyone wants to know if I believe in ‘this stuff’ because it perplexes them, I provide them with something that they don’t want to think about, although it’s all actually just special effects…

These are all possible interpretations but basically I was showing what the media shows us. The interpretation is available, multiple interpretations. I know what my own is.

The reason I used the gospel choir on the soundtrack is that the compulsive rhythm aims to drive you to belief. The construction of the work [two minutes soundtracked, two minutes silent] is an attempt to demonstrate at least two modes of viewing, immersive and distant scrutiny. You have the option. That’s the situation that I consider all of us to be in, that’s why I’m sharing it. This is a long way from witchcraft, paranormal – anything like that.

That’s actually one of the reasons that I wanted to do this interview. The prevalent theme that I found in researching your work has always been opportunity.

When you look at an art work you have to start somewhere. I find that I am interested in setting up situations that are empathetic to people. You can enter into it or you can withdraw from it but you have to realise that that’s who we are as a society.

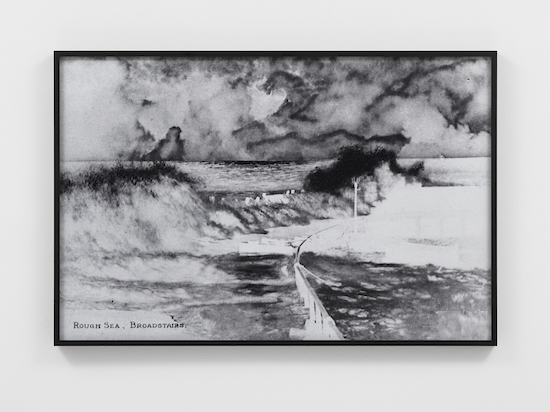

Susan Hiller, Rough Moonlit Nights, 2015, Archival dry prints, 51 x 76 cm (each panel) 20 1/8 x 29 7/8 in © Susan Hiller, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

That reminds me of the quote from Gertrude Stein’s 1926 essay ‘Composition as Explanation’ that can be paraphrased as: Nothing changes from generation to generation except what we are perceiving at that moment. I feel that that links directly to what you’re saying. From generation to generation, the setting has changed. It’s the evolution of Belshazzar’s Feast. The idea that we are now being surrounded by media, but it’s being condensed so as to stop us from noticing.

That’s interesting. I can’t necessarily comment on that directly but I do know that artists can do a variety of different works but they’re always about the same thing because you only have one being. You just find different ways of speaking about it.

In my recent Resounding works [audiovisual installations including transcriptions of the big bang, pulsars and plasma waves; a morse code message from a lucid dreaming experiment; static interference from radio and television programs containing traces of the big bang; and the voices of individuals describing their experiences of unexplained visual phenomena], I’m attempting to represent scientific descriptions of cosmic phenomenon.

These phenomena are only communicable through mathematics (which I don’t understand) or through sound. Scientists translate light waves to sound online for our benefit. So when we experience the sounds, what are we actually experiencing? How does that relate to the way that we try to speak about these sorts of things and to feel their reality?

I am trying to focus on ways of creating a structured situation for people to realise how distant we are from experiencing some things that are said to be part of our world, knowledge that needs to be taken literally on faith….

It’s quite similar to your piece The Last Silent Movie [A 22 minute video piece consisting of endangered and extinct languages spoken, subtitled on a black background]. I remember hearing something about the discussion around what it means for a language to die and a community to die but what I found most interesting is that there are things which used to be explained with these languages that we no longer have terminology for. The idea that we can’t talk about certain things because we either don’t want to or that we don’t have the tools to describe them is an interesting dichotomy.

That’s the situation we’re at – if we don’t start learning soon, we’re not going to be here. I feel quite apocalyptic at the moment.

I think what you’ve said is true, although it wasn’t my intention in that work. It comes across because using the human voice is physical. Your relationship to someone talking to you is a physical one that’s very special. It’s like touching. It has an intimacy that the other senses don’t provide.

Of course, you experience people in other ways, but it’s not the same. When you hear people talking, it’s vibrations touching your ear. You compile an image of who they are. The Last Silent Movie provides a much more complex experience than just reading about a dying language.

It’s interesting you should mention that. Researching for this interview, I had one of your works playing on some laptop speakers. My partner was in bed and she got up to ask me to use headphones because this sort of disembodied tinny voice was echoing down our hallway, sounding very unsettling. I think particularly because of the context of the paranormal within your artwork.

That’s interesting because there were not – and now are – a lot of artists exploring the paranormal. They’re doing things like séances. To me that’s not getting anywhere. The fear that people have is very real because it’s a whole area that our society categorises as frightening. It’s death, it’s haunting, it’s ghosts, blah blah blah… It frightens people. But is anyone frightened by a recording of a deceased musician, or watching deceased actors in an old film? These contradictions are part of our culture. If we were from a different culture, we would have a very different attitude towards this kind of thing.

Even around 100 years ago, there was the occult boom in Europe – the Parisian Mesmerists, Crowley, etc.

Of course, it was a way of broadening out what the mind is. I suppose it is still continuing. The fact is that people want to see aliens when in the past it would have been angels. We have to put it in our own terms. It’s the problem we have when faced with certain experiences: How can we represent it?

Do you feel like these experiences can sometimes be limiting due to their ease of reproduction? For example, I was introduced to your work as “This is Susan Hiller, she is a feminist artist making art about feminism” however there are other viewers focusing more heavily on the paranormal or ‘other’ aspect of your work, giving it context that way.

I’m all these things but I resent all of this categorisation. There is a difference between art and advertising. Advertising targets a potential market that’s already recognisable and you want to target with your imagery. If I include women in bikinis, I assume this will appeal to a specific group. I don’t think that’s what art tries to do.

Art creates an audience that was previously disparate from the way it presents un-codified ideas in some kind of formal order to be considered. You end up with an audience that perhaps recognises itself as sharing some insights, but it’s not like you’re all wearing the same trainers.

The artists who target known groups and use their art as a logo do very well commercially. I’m not saying that it negates their work but it’s different from my work, maybe because I’m from a different generation.

I’m not sure if it’s necessarily generational. If I were to think about the work that I was making in relation to a particular audience then I wouldn’t really consider myself to be making art, I would be producing a commercial product.

I’m not sure it’s that close a relationship. If artists gave up as soon as they sold work, if they considered selling work to be reprehensible, nothing would happen. There has to be a balance.

Susan Hiller, Homage to Marcel Duchamp: Aura (Blue Woman) 2017, Giclée print, 182.5 x 121.5 cm

71 7/8 x 47 7/8 in © Susan Hiller, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

With art, you can be sidelined. You can be taken away from what you could ideally be doing. Success can be one of those things that can sideline you. It would be very depressing to think that only mega-multi-millionaires were able to experience your work. These people are not necessarily always nice or interesting. It would create the question of exactly what you were doing for this to be the group your work appeals to. One of the joys of being an early conceptual artist was that nobody bought anything so we were all very pure!

When I first showed Dedicated to the Unknown Artists [an early work consisting of postcards, charts, maps, one book, one dossier, mounted on fourteen panels], I did a piece of writing that described myself as a curator. This was me introducing the act of collection as something that you do in art. A collector expressed an interest in purchasing some – not all – of the postcard panels. Of course, I said no. I didn’t realise that nobody had really seen a work like this that had fourteen parts. It was looked at like different drawings or paintings with a shared formal language instead of a conceptual project in fourteen sections.

Nobody ended up buying that work for about thirty years until the Tate bought it. We were also very privileged in those days. it was cheap for us to live and cheaper materials were what we had. It necessitated this kind of making.

I think that kind of living was still going on even in the early 1990s. I do look on people who were able to leave art school and immediately support themselves with the dole whilst concentrating on their work with a certain amount of envy.

And so you should. In the 1970s, in London, that’s what everybody did. They weren’t sitting around, they were working. This was how you supported yourself as an artist or a writer or musician. Art school was free. You probably received a maintenance grant. You didn’t have to work however many hours as well as studying, it’s probably one of the reasons art schools are far less exciting nowadays. The students aren’t there half the time because they’re working at paying jobs. This is a great cultural tragedy.

People’s are increasingly making use of one-liners in art. Only artists doing very well financially can actually afford to make slow, complex work. We are seeing a mass exodus of artists from this country because they can’t afford to live here. What artists need is time, that’s the only thing you can guarantee.

There are some advantages for artists working now. There has never been access to information like we have. Almost everything is available freely online. It’s so vastly different to how things were before. Making works like you made with Channels [a multi channel video installation] used to be almost impossible but now we have the ability to show audiovisual work or digitally focused work anywhere in the world. We can send works to galleries via email.

You have to be very tough to continue under difficult circumstances. You need to recognise them as difficult circumstances and push on. We’re never alone, you know. If you have an idea, you must recognise that there will be many other people with this same idea. It’s always surprised me, as someone who has taught a lot, why some new graduates suddenly are taken up and others are not. Looking at this from a distant perspective proves it’s really not a horserace where one horse wins. I don’t know what it is like, but it’s not like that. You just have to work.

Somebody asked me a few years ago, “Why are you hiding in Britain?” The reason is that I have no context here. When I arrived here, nobody knew who I was. To this day I ask myself why I am still based here not out networking in New York or LA, and I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s just not for me. I like the situation of being in a world that I don’t know very well. It’s interesting for me. It’s all surprising.

Hiller’s work can currently be seen at the Staatliche Kunstammlungen, Dresden, Germany, and her work was the focus of recent survey shows at The Polygon, Vancouver, and at the Officine Grande Riparazioni, Turin