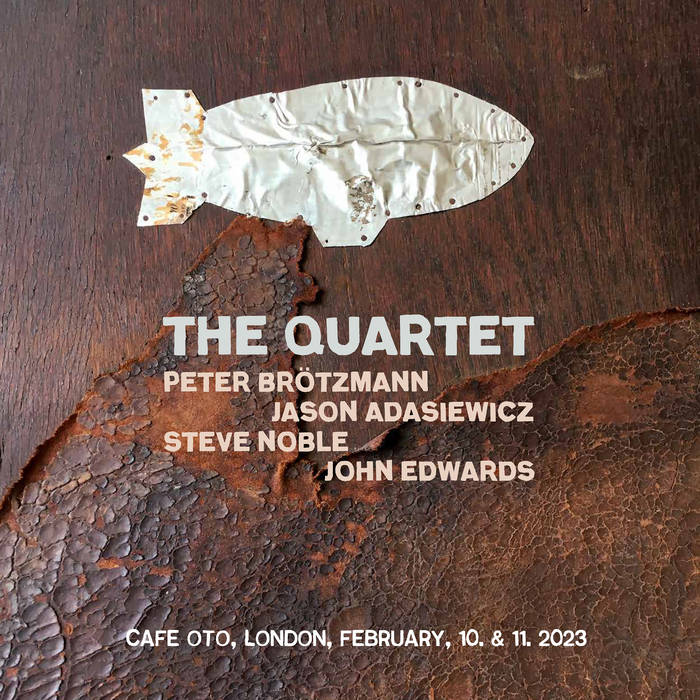

The Quartet with double bassist John Edwards, drummer Steve Noble, and vibraphonist Jason Adasiewicz was recorded at London’s Cafe Oto in February 2023, just a few months before Peter Brötzmann’s passing. The stark finality of this sentence is hard to swallow. The German free jazz saxophonist and clarinettist was one of those larger than life characters – and, yes, true legends – that felt as if they would go on forever, privy to some arcane ways of cheating death.

While he ultimately couldn’t escape the reality of what expects us all, The Quartet is as remarkable of a coda as anyone could wish for. Since first hearing him play in 2005 with Joe McPhee, Kent Kessler, and Michael Zerang, my every encounter with Brötzmann’s music was a minor epiphany, whether he was blasting jazz metal with Marino Pliakas and Michael Wertmüller or exploring the blues with Heather Leigh. The four sets presented on this album are no exception, even as they capture Brötzmann at his most tuneful and introspective.

Over the past decades, he had been increasingly exploring his lyrical side, moving away from the ideologically fuelled punk ferocity of his earlier years – “jazz has always had a revolutionary approach, I keep that going,” he once remarked in an interview – towards post-bop and blues tinged free jazz. Then, pneumonia contracted during Covid forced him to further reinvent his playing. Across the four sets, each of his signature squeaking, overblown machine gun barrages is thus tempered with long, lyrical improvisations, alternately played on alto saxophone and clarinet.

He opens the album with one of these sustained, melodic but forceful alt sax lines, only to then harden the edges of his curling phrases, biting with conviction into a soaring lick. The work of his colleagues is just as impressive. Edwards and Noble, in particular, are an unstoppable force. Their bass and drums patterns lock into tight, rumbling rhythms like a train passing by, then move away from each other, constructing sparser architectures and opening up spaces for the reeds’ gentler shapes. Meanwhile, Adasiewicz lays down layers of vibraphone accents, splashing harmonic colour over calmer segments and punctuating furious attacks with sparkling flair.

While the quartet hadn’t played together since the mid 2010s – Mental Shake, also on Otoroku, was recorded in 2013 – they appear in telepathic sync, as if they had been rehearsing together throughout all those years. Their chemistry is especially impressive during transitions, switching between uncompromising intensity and bouncing grooves, using atmospheric, lowercase improvisations and the odd solo to launch into the sort of collective skronk that brings to memory the frenzy of Brötzmann’s large, eight and ten piece ensembles.

The stream of archival recordings of Brötzmann’s music will likely continue in coming years – Butterfly Mushroom with Paal Nilssen-Love came out in December via Trost – but The Quartet feels like the most fitting swan song and testament to his amazing career. This is really it. But like the messages that heads scrawled all over New York when Charlie Parker died, perhaps we’ll see a similar motto cover the walls of his Wuppertal and each of the many places he played and left a mark in. From London to Rio: “Brötz lives!”