Of all the locations where you can identify the origins of British DIY indie music, the King’s Road is as good a place as any to start. Not just because it was here that Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren ran their SEX boutique – where John Lydon auditioned for the Pistols and the Bromley Contingent found an ad hoc youth club – but because it was also where Dan Treacy, frontman of Television Personalities, lived.

The band’s debut EP, Where’s Bill Grundy Now? (1978), its initial pressing paid for with money borrowed from Treacy’s mum, was among the first clutch of British DIY records. Its most enduring track, ‘Part-Time Punks’, was a sardonic swipe at the weekenders who gathered on the King’s Road in bondage trousers and leather jackets, those who looked “the same” and didn’t “use toothpaste” but had “£2.50 to go and see The Clash”. I hated it at the time, but then I was a teenager and, while I would have denied this, suspected it was about kids like me, because everything’s about you when you’re that age.

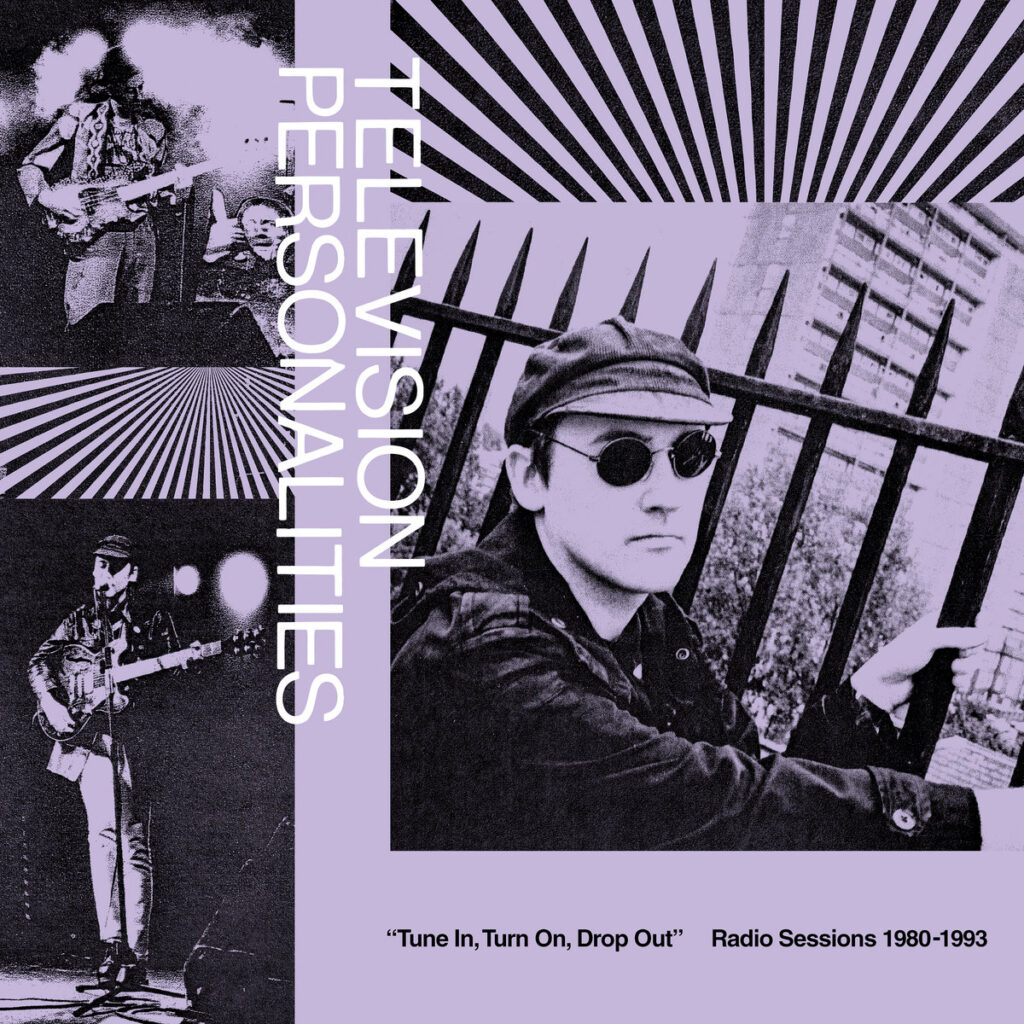

Championed by John Peel and re-released by Rough Trade, the EP sold more than 25,000 copies in 1980. Proving you could do things on your own terms, Treacy was on his way, but to where exactly? Television Personalities’ subsequent odyssey never brought much commercial success. Just the reverse. Treacy succumbed to a heroin habit and spent time in jail at the turn of the century. And yet, when you listen to Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out, which gathers together radio sessions recorded in 1980, 1986, 1992 and 1993, you find yourself reflecting on how influential Treacy, who retired from live performance due to injury in 2011, has been.

It’s not just that he was among those artists who showed that it was possible to release a DIY record and get attention – alongside the likes of Desperate Bicycles, Scritti Politti, Kleenex/LiLiPUT – but in creating a particular lo-fi aesthetic which became the end point in itself and detectable in so many bands that followed. Think of the C86 generation, numerous Creation alumni (Alan McGee was a fan and sometime Television Person Ed Ball worked at the label) and the many American acts, including Pavement and Kurt Cobain, that have name-checked Television Personalities down the years.

As to why and how Television Personalities’ influence spread so far, it may be that this compilation is more useful in providing an answer than the band’s studio albums in that it better captures their essence. The idea of Treacy, in the broadest sense of the word, as a busker is useful here. He hated rehearsing, didn’t like to play shows with a pre-planned setlist because he wanted to keep his bandmates on their toes. Ally this seat-of-the-pants quality to songwriting that’s straightforward in terms of chord progressions and Television Personalities sound like a band to be emulated.

Except it’s not that easy. The skewed dynamics of Treacy’s best songs are more difficult to replicate than might be supposed. Then there’s the stark beauty of so many of them. Once Treacy got past what we’ll call, for argument’s sake, his juvenile novelty song phase, his writing deepened and, without losing its directness, satirical edge or myriad pop culture references, became more subtle. He grew up.

As you might expect, the first session here, recorded for John Peel in the summer of 1980, is closest in spirit to Television Personalities’ recordings in the 1970s. ‘Look Back In Anger’ is a beat-punk song that channels the aesthetics of The Who or The Action, reflecting Treacy’s fascination with mod culture. ‘Silly Girl’ (“What have you done now?”) is slight but lovely. These are songs of their time sonically, a year when Spizzenergi and Joy Division topped the nascent British indie charts, and yet somehow a little otherworldly.

Six years later, Television Personalities once again fetched up at the BBC, to record a session for Andy Kershaw. By now, Television Personalities were four LPs in and it shows. In Treacy’s songwriting, the everyday and the surreal mingle, and not just in fan favourite ‘Salvador Dali’s Garden Party’. The melodies are stronger. It seems apt to make comparisons with Syd Barrett and Jonathan Richman.

And yet that in itself reveals one of the pitfalls when approaching the music of Television Personalities. Talents such as Barrett and Richman too easily get sidelined as maverick outsiders when they deserve to be at the centre of rock’s grand narrative. Treacy hasn’t been as influential as either of these figures, so there’s a risk of not recognising Television Personalities as DIY and lo-fi pioneers, important within a musical story that’s still unfolding.

If that in turn makes it sound as if Television Personalities were amateurish, this too is a misreading. By 1992, when Television Personalities recorded a session for college rock station WMBR, this was a dynamic band adept at exploring the dark corners where Treacy’s songwriting was leading them. A version of the Buzzcocks’ b-side ‘Why Can’t I Touch It?’ is a particular highlight, less studied than the original and all the better for it. The song also reveals how, while Treacy doesn’t have a huge range, he was by this point a great singer in terms of working with what he had. A WFMU session from a year later, available to download if you buy the LP, is scratchier and less satisfying, although it’s difficult to tell how much this is due to the band’s performance or the sound not being of the highest quality.

No matter, just on the basis of the three sessions included on the vinyl version, Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out is worth your time. More than this, because it captures Television Personalities in the wild at three distinct points in their development, it’s a fine introduction to a maverick talent who can break your heart and make you laugh out loud over the course of a single song.