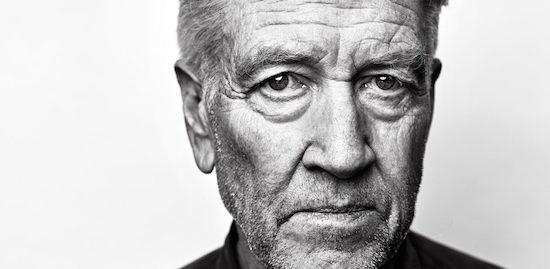

One of the highlights of a working trip to Prague last spring was a visit to the Kafkaesque exhibition at the DOX gallery. I was delighted, but not surprised, when I stumbled across a set of ten gloomy, wry and haunting lithographs by David Lynch, who has died this week at the age of 78. Lynch’s desire to be an artist predated his wish to be a film director, and even when he eventually enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1967 he was already working as an engraving printer before finishing his first short film, Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times).

David Lynch represented a true bridge from the most important cultural movement of the 20th century – that of modernism – into the artistic language and practice of the 21st. Nobody else featured in the incredible collection of work at DOX so perfectly represented the modern equivalent of Kafka’s ideas. This was not just in terms of buttoned-down neuroses but the less frequently mentioned humorous warmth, the clinical diagnosis of a zeitgeist, and the astute navigation of the margins between realism and surrealism. Lynch’s work was at home next to sculptures, films and paintings by the Chapmans, Jan Švankmajer, Nicola Samori and Marek Shovànek not because his minor celebrity ‘bought’ him access to the room, but simply because as well as a being a great filmmaker, he was also a great visual artist. But why stop there? He was also a great story teller, a great actor, a great sculptor, a great writer, a great cartoonist, a great musician, a great TV show creator, a great bedside lamp maker, a great meditator, a damn fine coffee drinker, a great meteorologist, a great teller of jokes and so on and so on. Whether you want to look at the physical manifestations of his constant, restless, cosmic curiosity writ large and cohesively as a gesamtkunstwerk is up to you but let’s take some time to think of him and praise him as a brilliant artist.

How I came to think of him over time – an entire adult lifetime of relishing in and wondering/ marvelling at his work – was as a mapmaker and as a draughtsman. He was an expert – simply the best there was during my lifetime – at rendering the true occult dimensions of life and drawing pathways through life. At the age of 13 when my friend Martin and I sagged off school one afternoon we chose to watch the film Eraserhead which his elder sister had taped onto VHS off Channel 4, thinking (very, very erroneously) that it would be a slasher “you know, like Halloween”. I remember we laughed, wide-eyed, all the way through, but then weren’t able to talk about it for at least a week afterwards. Yet this wasn’t horrible, ugly, mean adult life intruding into our blissful, innocent childhood, but David Lynch rushing to find us – just in time – in order to give us a weird map. A map that would make absolutely no sense to us. Until one day it did.

Before Mark Fisher, before Arthur Machen, before John Gray’s Straw Dogs, before The Fall even, I had David Lynch, slowly pulling the curtain back to gently reveal the occult structures and systems and pathways guiding me through life. I had no context for who Lynch was or where he was from when I was a boy. It was only three years later when at the age of 16, notionally on the edge of adulthood, I saw the Pixies live in Manchester end their set with a cover of Eraserhead’s ‘In Heaven (Lady In The Radiator Song)’. It loosened the teeth in my skull. I realised I had work to do. Who the hell was David Lynch?

Within two years Blue Velvet had become my favourite feature film. It remains so today, or that’s what I say at least if anyone asks as I’ve seen it more than any other movie by a margin of about six times. This means, in theory at least, I’ve had a fair amount of time to wonder about its own peculiar, voluptuous, hypnotic dimensions. I’m not a fan of people talking about pop surrealism when it comes to Lynch as it suggests weirdness as an intrinsic affect as if it were a type of ambient decoration (a mistake plenty of his copyists have made). Neither do I like the idea that he is trying to reveal some literal underbelly of American life, like an exposé; “the evil behind the picket fence” or whatever. For me, Blue Velvet is another weird map, this time one through the dimensions of Freudian death drives and Oedipal complexes. It’s universal, not just middle American, but then I don’t want to dictate what other people should think about such a generous, visionary, eternally inventive piece of art either.

Even speaking professionally, as a lowly culture writer and editor, Lynch has had a profound guiding effect on me. The idea that you don’t need stimulants (any stronger than coffee at least) in order to do original creative work was a lifesaver for me, and the practice of sitting down with a freshly brewed pot, a pad of paper and a pen in order to record original ideas as they come to you, is about as good a starting point for young writers and other creative people as I’ve ever heard. Record every idea you have, kickstart projects even when you don’t fully understand what they are, always be working, chase ideas down rabbit holes. Nothing was ever really wasted for Lynch, so what other people might have considered a bunch of odds and ends – experiments with DSR digital cameras, a ‘sitcom’ about a family of rabbits, a film about filmmaking, a continuing fascination with factories and other industrial sites, Polish folklore – became the incredible, if largely inscrutable Inland Empire.

Lynch was ahead of his critics and fans alike every step of the way, subverting expectations while constructing a cohesive body of work. Much has been made of The Straight Story, and how it doesn’t really fit into what people consider typical for him, but it is the most ‘Lynchian’ of the lot: a road trip as psychological journey, the beauty and weirdness of quotidian, non-metropolitan life, the random cruelty of existence (this time, thankfully for its family friendly rating, as it applies to deer rather than people). Even when he tested the patience of his viewers – the cruelty dished out to several characters in Wild At Heart; the complex sexuality of earlier films congealing into something far nastier in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me – there was simply too much creative benevolence and brilliance on offer to ever tip these projects over. Much will be said about how films such as The Lost Highway introduced an entire generation of mainstream cinema goers to experimental film, and rightly so, but his absolute lack of worry is the key element here. His conviction was infectious. It was remarkable – when you think about it – how rarely he was called pretentious. In fact, no matter which film you consider, it would take a special kind of halfwit to brand him pretentious.

As great as all of his work was, in terms of big projects Lynch really only reached his plateau in the 21st Century. Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire and Twin Peaks: The Return are works of art for the ages. They are important – a word I try not to use until I absolutely have to – treatises on psychosis, trauma, metaphysics, thresholds between different states, time and what it means to be human, with everything that implies about considering one’s mortality. I’m sure all of us will be gaining insights into our own existence for a long time to come thanks to these works alone.

Thank you David Lynch.