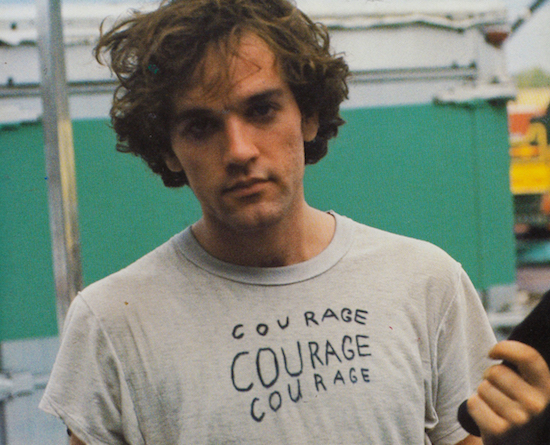

I’ve lived with his grainy voice for years now. Super-8 dreams signposted a way to be. Pre-internet, I’d pore over inlay sleeves, searching for messages. His cryptic imagery folded into my DNA. A few words exchanged, a hand held. His picture: a crumpled T-shirt bearing the hand-scrawled message ‘courage, courage, courage’ was possibly the most profound thing I’d ever seen at that point.

As if on a whirring projection I watch myself in Audenshaw walking, brooding, wondering, dreaming, a flickering figure on repeat. Did I reach my potential? What became of those dreams? It’s all enfolded into REM, my past, my future. I can’t really overstate how obsessed I used to be with REM, nor how much a part of me they are.

I first became aware of their existence with the release of Out Of Time in 1992. It impacted strongly on me; after hearing it I travelled backwards into their discography and bought every album, one at a time as I could afford it with my pocket money, each time delving deeper into the worlds within.

But Out Of Time was the entry point, and I seem always to ‘see’ this album as a burnished gold entity, something that holds within it the porous vivid state of youth and the humdrum environs of Audenshaw. Its leylines – a roundabout, a bridge, a reservoir – a small but potent matrix of my awakening mind, now overlaid with the strange visions of a man from Athens, Georgia, a land so distant from my own topography. I became obsessed with REM, and in particular their frontman, a former art and photography student called Michael Stipe.

They pushed at the statues for harbouring ghosts

He’d scrawl curious phrases on his clothing. His hair might be mustard yellow, his eyebrows purple. Eccentric visionary, transmitting messages from a burnt sepia landscape. His worlds packed with cryptic instructions, allusions and oddments: folk art, whirlygigs, trains. All these things fascinated and fed me. Live, he’d veer from introversion to wild abandon, lost in Stipe-scapes. I sang along to REM in my bedroom so much I think it physically re-shaped my vocal cords. That rich voice shot through with melancholy and longing set a kind of blueprint. The unstable, grainy behaviours of real film processing in which moments are caught and light and mood are ever-shifting between frames – this Stipe-ian way of perceiving the world wrapped itself around REM, forging an aesthetic, forming them, part moving painting, part rock band. Depth, intrigue, heart, art. So many reasons to declare Michael Stipe the Ultimate Arty Pop/Rock Icon.

To revisit Out Of Time now is to unleash a phantasmagoria from the ark; I open the lid and am buffeted by a vortex of bleached-out memory poltergeists. I find it a bleak album. ‘Shiny Happy People’, ‘Radio Song’ and ‘Me In Honey’ are prozac-y red herrings; these bright flashes hide a deeper darkness behind. ‘Belong’, ‘Half A World Away’ and ‘Texarkana’ brim with keening wistfulness, but ‘Low’ and ‘Country Feedback’ particularly affected me.

I’ve been laughing, fast and slow / Moving in the still frame / Howling at the moon / Morning found me laughing / Up and down, down / Low, low, low

Disjunctions and intimations of dread. Haunted strings pull queasily over an organ drone thick as oil. Guitar nags anxiously at the edges. Was it a description of a breakdown, a split from reality? A hallucination? I was transfixed by the unsettling, fever-dream video in which paintings come to life, marble statues twitch and spectral presences glow.

This flower is scorched / This film is on / On a maddening loop

‘Low’’s counterpart, the even murkier ‘Country Feedback’. Again, the sense of being trapped in the thick dirges of a dream; another painterly video with its random, episodic moments; fireworks, street scenes, a ferris wheel. Dark apartments, figures at windows; absences; frames sped up, slowed down, obscured. Musically and visually, ‘Low’ and ‘Country Feedback’ filled me – still fill me – with a deep sense of unease and foreboding. At the time, both these tracks triggered some sensation in me I did not quite understand. I loved their dense mystery, but what else did they seem to foretell?

Chronic town / Poster torn / Cages under cage

REM’s first release proper was the Chronic Town EP in 1982. I love/d this EP for its sheer gleeful energy, bursting with intricate, frenetic riddles. Manic-gothic. A cheeky gargoyle on the cover. Something in my brain and fingers reacted immediately to Peter Buck’s style, a deft, twining language that percolates through REM songs like unruly ivy, enervating them. It compelled me to pick out the single, intricate lines hidden in the fretboard like spidery pencil drawings.

I wonder if Peter Buck receives his due as a guitarist. I was always struck by how his right hand doesn’t rest on the guitar body; it isn’t anchored in any way; all those deft arpeggiated notes played at speed are delivered with his hand ‘free-floating’ – incredible, and incredibly difficult. Any number of those early frenetic tunes – and many more besides – require considerable articulation, detail and precision. Along with Andy Gill of Gang Of Four, Peter Buck has had the biggest influence on my guitar playing.

On 1 September this year, I went to see Michael Stipe in conversation with Miranda Sawyer at the ICA in London. I hadn’t seen much publicity for it; it seemed like a secret; I almost didn’t go. It took some time to get used to the fact that he was bodily, actually here in this small room. Just alone, with no ‘people’, no security. Simply talking about his new book of photographs.

He spoke with a quiet intensity and the audience hung on his every word, his every gesture. He was as Michael Stipe-esque as you could ever possibly wish for him to be. Modest yet completely commanding. Utterly authentic in a way that immediately made me want to improve myself in all matters of art and the soul. How lucky we are to now see Stipe’s second act, post-REM, his incarnation as photographer/visual artist – not that he ever stopped being those things, only now they rise to the surface.

A handshake is worthy

I’m grateful to Danny Saul for taking (unbeknownst to me) the above photograph, as it captures what felt like a genuine and pleasant meeting. Michael Stipe signed my book (he is left-handed) and we exchanged a few words. His alert gaze locked onto my face and it was all I could do to stutter out in a few short sentences how much he meant to me. (I did in fact mispronounce ‘REM’.) He was solid and compact, seeming to glow with some interior treasure, like a gemstone. It’s possible I’m talking shit; but anyone knows what an encounter with a hero does to the sensibility. Many people wanted selfies, but I just wanted to shake his hand. When I reached out, he seemed surprised and happy to do so, as I think the picture captures. (That hand, that expressive hand of his!)

REM, and the visual worlds of Michael Stipe in particular, impacted on me indelibly, and became part of my DNA. I can’t imagine existing without them. After we shook hands, my insides turned to fireworks, and as I moved away from the table I suddenly started to sob with all the pent-up emotion of my younger, REM-obsessed self, who never would have dreamed such a meeting possible.

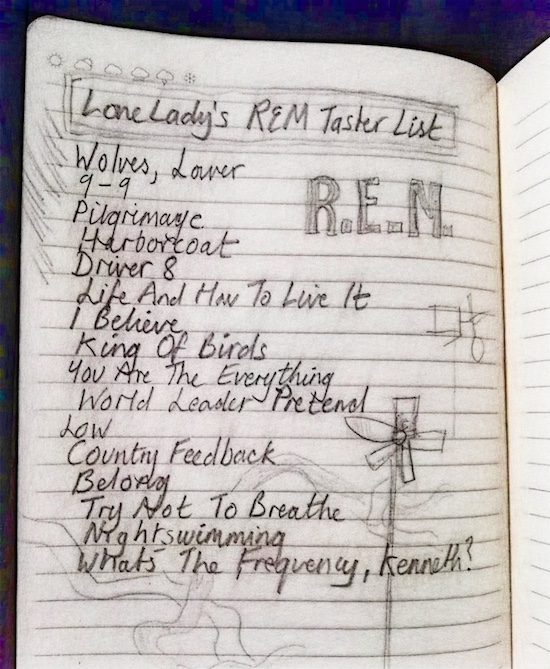

The huge REM At The BBC boxset is out this Friday, and is also available to stream and download; Lonelady’s own Introduction To REM playlist is below.