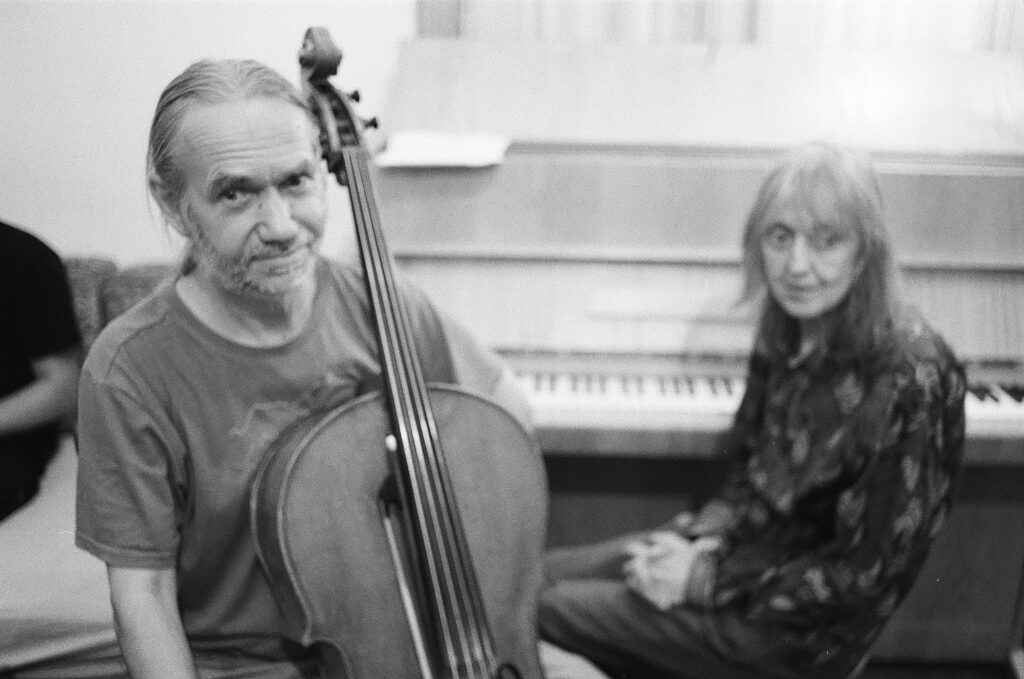

“The music seeped through mutual understanding. It was a result of being together,” muses Vojtěch Havel in the 1992 poetic film portrait Vojtěch & Irena H.. “We sit, start to play, and feel a profound, absolute connection.” In the short movie, they finish each other’s sentences, and the word “understanding” reoccurs often when talk turns to his shared project with his wife. The closeness of playing intimately, next to each other and for each other, whether on organ, piano or their violas de gamba, formed the fabric of their serene compositions. They produced ethereal ambient with Baroque instruments, medieval tonality and murmuring, “shadowy vocals” based in folk forms; theirs was an extraordinary union.

Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi stitched together disparate sound worlds and temporalities, making music both historical and modern. In the shadows of cathedrals and monasteries around Prague – where one can to this day still find corners with atmosphere unspoiled by later centuries – they developed a common musical language. It hasn’t lost its power over the decades, and over time has captivated fans including Sufjan Stevens, The National’s Bryce Dessner and audiences at experimental music festivals such as Utrecht’s Le Guess Who. Their music was both revelatory and mysterious, not only because it emerged from the depths of the alternative scene in communist Czechoslovakia. It was something else.

The lines between their individual roles disappeared when the pair were performing or composing – the connection was almost telepathic. “We have crossed a certain border [of] lending oneself to the other,” the duo said elsewhere. For this and many other reasons, it was heartbreaking to read the news last month that Vojtěch Havel passed away unexpectedly. He had just come home from a small tour in the Faroe Islands, and the day after he returned to a small village outside Prague. Vojtěch went for a walk in the woods, and on the way back, he collapsed in the garden he took care of with Irena.

The two met in the early 1980s. Irena studied natural sciences but wanted to play music, and Vojtěch had just completed his time at a conservatory (on cello and piano). From the first moment, it was clear that music would be part of their communication. In the mid-1980s, they joined an experimental ensemble, Capella Antiqua E Moderna, which led them through interpretations of European classical music to their primary instrument, viola de gamba, and to “the strange world of churches” (as they titled two songs on their 1992 album Háta H.)

After the 1989 revolution, they became close to a loose network in the esoteric underground. People like experimental folk singer Oldřich Janota, tape looping minimalists Richter Band and ambient musician Jaroslav Kořán, and they began composing meditative music with a different sensibility. Compared to the boisterous Zappa-adjacent and booze-soaked sounds which provoked the state authorities, this music was meant instead for tea rooms and spiritual sites, as if occupying some place where time flows anticlockwise. While the esoteric underground in the UK was tapping the mainline to occultism, the Czech iteration was drawn by the light and immersing itself in meditation and Zen Buddhism. After years of restrictions under communist rule, new spiritualities – especially New Age – were booming in the freshly democratic country.

The two gradually gravitated towards raga-like swells, worked with Tibetan bowls and recorded an album of gamelan, using instruments borrowed from the Indonesian embassy. In a rare 1995 interview for the magazine Rock & Pop, they discussed their inspirations. “We didn’t know Indian music; our inspiration came from elsewhere, specifically from old European music. It may not seem that way. But Bach and all those masters use minimalistic ‘laps’ in their compositions. Early baroque music is slightly similar to Indian ragas; they are simple, all in one key. Similarly, gothic church choirs are close to Arvo Pärt. These are roots of our music.”

Such gentle, timeless sounds didn’t match the fast pace of political change in the country in the early 1990s, and despite being prolific, Irena and Vojtěch were rarely reviewed in the Czech music press. The duo was unspoiled by ambition and capitalist desires – they created music in solitude and in a very DIY fashion: recording on their own, designing their own album sleeves, waiting in long queues at the printers, booking their own shows, selling merch in the streets, and touring by bus only with the instruments they could carry. They seemed to find harmony in the cycle of travelling, performing, and recording.

One CD purchased in Copenhagen’s streets changed everything, however, lifting the duo from obscurity, although it took time. A disc containing their 1991 album Little Blue Nothing was given to then 14-year-old Bryce Dessner, who later became composer and guitarist of The Clogs and The National, by his older sister Jessica. She had arrived in late August, 1993, to teach dance and study abroad. “I was jet-lagged, walking around the city alone,” she remembers over email of her first day in the new town: “I heard this totally other sound, different from the rest of the sounds of the city, long, melancholic notes. I found Irena and Vojtech playing on the street. She was seated on the ground in front of him with her bells. He was playing his cello, which looked as if it had survived a shipwreck. I listened until they were done playing, the only person sitting there. They had only one CD for sale: Little Blue Nothing.”

Bryce Dessner adds: “We were both completely taken with their sound and approach to music.” In 1996, they even took a trip by train around Eastern Europe and went to Prague – brother and sister spent days wandering around asking about Vojtěch and Irena, eventually finding a small jazz club where they had often performed, and bought a few more records there, including Háta H., which they listened to endlessly.

They had such a huge impact on work of both siblings: “My sister would choreograph dances [to] many of their pieces over the years that were performed in downtown New York dance venues,” says Bryce. “I often thought of their music as related to the music of Meredith Monk or even Moondog and Harry Partch, but there was something so individual and so mystical about it that it was hard to quantify. When I founded my chamber group Clogs, with four musicians I met at the Yale School Of Music in the late 90s, the Havlovi were very much an influence on our sound and approach.”

In the meantime, Dessner duplicated the CD of Little Blue Nothing many times, and mailed it to his friends. In the mid-2000s, when Vojtěch and Irena started their website, Dessner emailed them, expressing gratitude for their album changing his life as a teenager and leading him to become a musician. In return, he invited Irena and Vojtěch to the 2007 Music Now festival he organised in his hometown of Cincinnati – where they opened for Sufjan Stevens one evening in a 500-seat chamber music theatre. Dessner even created a string quartet, ‘Little Blue Something’, for the 2011 record Aheym with Kronos Quartet, inspired by the album that changed his life. “Their gentle spirit and open-mindedness were always so touching to everyone and their uncompromising dedication to the world of music they had created,” Bryce adds.

Little by little, Dessner was building awareness of Irena and Vojtěch’s music. Over the decades, their works have been perpetually rediscovered by younger generations of musicians and new fans, partly thanks to compilations like 2005’s Světelné Kruhy and especially 2021’s Melodies In The Sand released by Dutch ambient label Melody As Truth, which brought the Havlovi rave reviews from big music websites. Three decades later, once-neglected quiet music from the Czech esoteric underground is enjoying a second life – not only the work of Irena and Vojtěch Havlovi, but also ambient ruminations by Richter Band or Jaroslav Kořán through a series of reissues, or in the broadcasts of NTS, Kiosk Radio or other community radios around Europe.

“Because we spent all the time together, we know each other tremendously,” said Vojtěch Havel of his wife in 1992: “Therefore, we can go deep, almost to extremes in that understanding. Music depends on our relationship and results from such understanding.” He would later speak in interviews about their work as a “never-ending study of one relationship”, which continued for over four decades. They achieved the tightest communion of two people, in sound and silence. Time was persistent and intrusive when it took Vojtěch away, but the albums he and Irena made together can be listened to in an eternal loop.

Capella Antiqua E Moderna – Marnost Křídel (Vanity of Wings) (1996)

Vanity Of Wings collects music performed with the experimental ensemble Capella Antique E Moderna from the mid-1980s onwards. In these interpretations of centuries-old music, the past seems to illuminate the present. Through playing these compositions in churches, cathedrals and monasteries, Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi discovered the psychoacoustic intensity of old and new music resonating in these monumental arching spaces. Their intertwined violas de gamba echo on the album, powered by organ, double bass, saxophone, and trombone, resounding off the cathedral walls in patient drones. This collection released in 1996 includes some recordings previously released under the title Music Of Spheres (Hudba Sfér) in 1989, including ‘Mirroring (Zrcadlení)’, which proves the strength of the music they made at the focal point of the old world’s axes.

Oldřich Janota & Vojtěch a Irena Havlovi – Cesty 15 (1989)

The connection between Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi and experimental folk singer Oldřich Janota, who passed away earlier this year, would determine the Havlovi’s career and helped to bring their music to light. Janota had built a reputation at folk festivals in communist Czechoslovakia, which weren’t monitored by the secret police as heavily as activities in the underground movement. Gradually, Janota grew weary of classical song forms and started to experiment under the influence of imported albums by Philip Glass and Steve Reich. Janota – who was previously active in experimental ensemble Mozart K. – or in a trio with prog-rockers Richter & Fidler – slowly moved to meditative, repetitive compositions that matched his esoteric lyrics with landscapes both psychic and real. This is where he crossed paths with Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi in the late 1980s. “We learned to play weakly, to do soft and quiet things,” Vojtěch remembered of this period in one interview. The result of this communion was this five-track seven-inch in 1989, and the 1996 album In Between The Waves (Mezi Vlnami), which are set to be reissued together with live recordings from the same period.

Irena & Vojtěch Havlovi – Malé Modré Nic (Little Blue Nothing) (1991)

The journey of meditative repetitive sounds that Vojtěch and Irena embarked on was leading them towards India. After the revolution in Czechoslovakia in November 1989, all gates were open, and people could travel freely, but the problem was money. They decided to go busking in the streets of Copenhagen in 1993, performing with cello and violas de gamba, which soon earned them enough to buy flight tickets. They had only CDs of Little Blue Nothing in their bags, but even more important than their own journey to India, was to be the trips taken by the discs they sold here. One CD went to Bryce Dessner via his sister Jessica, and another, a decade later, led director Vincent Moon to make a documentary inspired by the album in 2009. The movie opens with words that serve as a fine invitation to listening: “The disc gave us the chance to discover a secret music. It sounded like the magic of all the musics of the world, melted with silences and echoes of history.”

Irena & Vojtěch Havlovi – Háta H. (1992)

Háta H. comprises 17, mainly improvisational pieces each shade into one another. They are free-floating landscapes constituting the sound world that Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi built for themselves. Tracks like ‘A Day Of Wistful Returns’ and ‘She Is Dissolving’ are minimalist piano etudes for four hands. In two pieces titled ‘The Strange World of Churches’, they create eerie instrumental textures with Tibetan bowls, bells and what Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi call “shadow voices”, gentle murmurs that come from a distance. Vojtěch’s ominous style on cello is best captured in ‘Mysteriously’ and ‘The Peaches Shade’. The gently quivering organ in ‘Sargasso Sea’ paired with gothic vocals is heavy, as if putting all the weight of time upon those listening.

Irena & Vojtěch Havlovi – Něžně Ke Světu (Tenderly to Light) (1994)

In an interview with the Czech music magazine Rock & Pop in April 1995, Vojtěch and Irena described Tenderly To Light as an “almost pop album”. Compared to their previous output, it was undoubtedly their most accessible record to that date, mainly because they abandoned “shadowy vocals” and mixed their meandering lyrics to the front – Irena tenderly whispers and half-sings esoteric lullabies about winds, blanketing silence, and velvety wings of mist that must have taken at least some inspiration from Oldřich Janota’s poetry. “We like it when there is a certain emptiness behind the text, nothingness. When it says something, but at the same time it says nothing,” she hinted in the same interview. Tenderly To Light is a montage of associations, dreams, and memories.

Gurun Gurun – Gurun Gurun (2011)

By the time the experimental electronics quartet Gurun Gurun approached Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi around 2010 to record violas de gamba for their eponymous debut, the duo was performing only in tea rooms and vicarages in the countryside to crowds of a few people. They were more famous abroad than home in the Czech Republic or Central Europe. “But they were complete heroes for us!” remembers Gurun Gurun’s Jára Tarnovski. “Their music, unbound by any genre, and their natural, almost pilgrim spirituality, resonated with us.” On Gurun Gurun, the group connects disparate contexts and sounds: Japanese vocalists with Czechoslovak socialist sci-fi, fractured electronics with soft soprano voices and acoustic string instruments. “The sound of two violas de gamba was essential. Irena’s and Vojtěch’s unexpected tempo shifts and dynamics pinned down our direction in the tracks’ structures. The meditative nature of their music is often remembered, but Vojtěch and Irena could be wild; they weren’t afraid of cacophony,” recounts Tarnovski. “They were such gentle punks with baroque instruments.”

Irena & Vojtěch Havlovi – Saving One Who Was Dead / Little Crusader (2022)

Vojtěch and Irena Havlovi have a longstanding relationship with film music. Since the 1990s, they have composed scores for poetic existential movies by Ivan Vojnár, such as 1997’s Way Through The Bleaking Woods (Cesta Pustým Lesem) and his 2003 television drama Forest Walkers (Lesní Chodci). In recent years, they have collaborated with director Václav Kadrnka, who also contributed to release scores for his 2017 Crusader (Křižáček), a fictional “road movie” set in the Middle Ages, and 2021’s claustrophobic drama set in hospital corridors Saving One Who Was Dead (Zpráva O Záchraně Mrtvého). For the former, they received the national film award for the best music in 2017. Both directors they worked with prefer slowness, silence, and space in their movies, which Vojtěch and Irena understood well.

Irena & Vojtěch Havlovi – Four Hands (2024)

Zachariáš’ 1992 film portrait Vojtěch And Irena H. ends with a close-up of husband and wife gently playing the piano, their hands intertwined as if in each other’s arms. Their album Háta H. closes with a piece for four hands on piano, and over the years, they kept returning to the intimate technique – after all, it was the idea of being close to each other and to the instrument, that inspired them to compose new material after 14 years. Four Hands is made of 19 new pieces for piano and organ, and at the end, the paths of both instruments meet in ‘Four Hands Piano & Organ’, which is the most beautiful minimalism the Havlovi ever composed. “By concentrating on one instrument, it is easier to focus on the details,” commented Vojtěch Havel earlier this year in an interview with Uni: “I feel that we managed to achieve even greater depth of communication than when we used a combination of vocal and cello, piano and cello…”

Havelka/Havel – Vanishing Mountain (2024)

The tape Vanishing Mountain, released only a few days before Vojtěch’s death, felt like a new chapter. It came following an invitation from guitarist Václav Havelka, a steady force within the Prague underground scene, who had previously released a collection of music reimagining Indian mantras, and has collaborated with musicians like Swans’ Thor Harris and James Tooth, aka Wooden Wand. It starts with earthy guitar, while Havel’s cello evokes the winning of a horse, or seagulls, offering a reminder of the disappearing of the wilderness. But later – with the assistance of Havelka’s 16-year-old son Šimon manipulating synthesisers – the music elevates to a place of wonder, astral drones and cosmic Americana. In recent years, Vojtěch Havel allowed himself to encounter and collaborate with younger artists more often – such as sound artist Anna Ruth and vocalist and producer Adela Mede – which promised new adventures into unmarked territories. It makes it all the sadder that further explorations will probably never materialise on record.