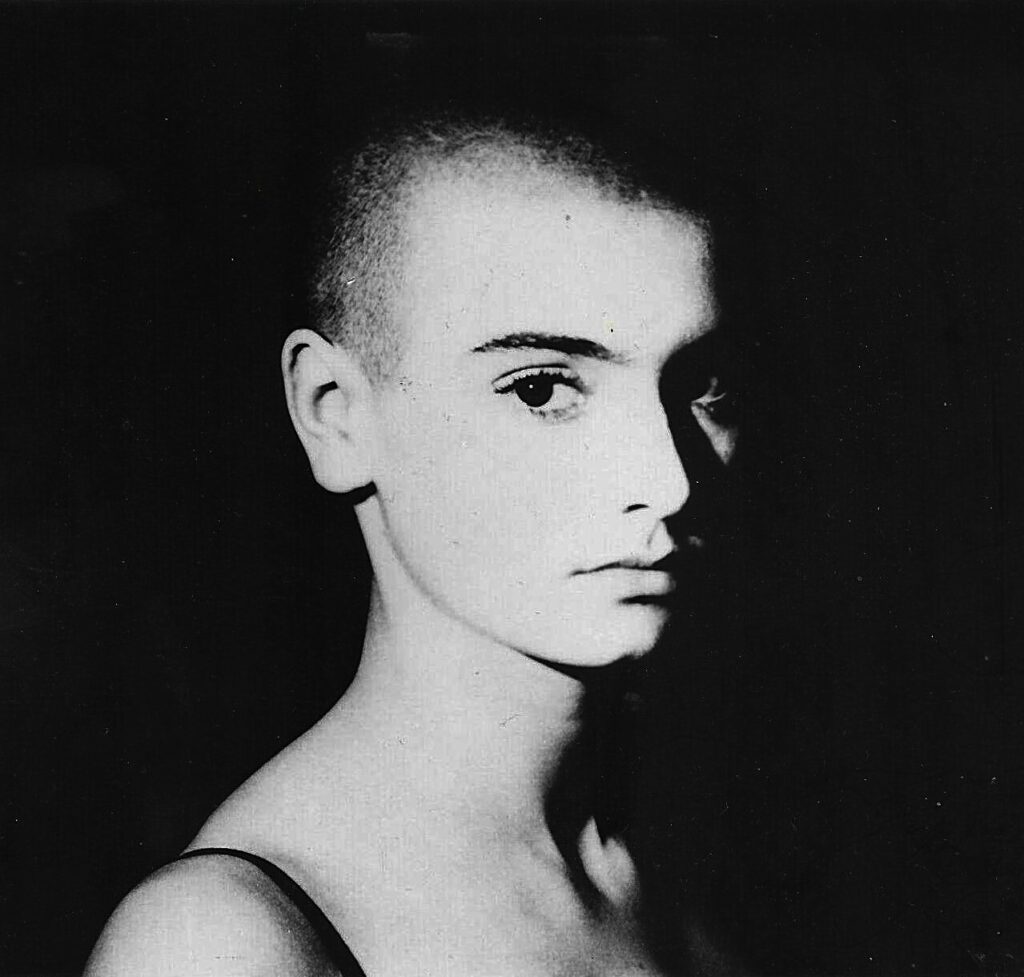

For years when I was younger, I was consistently overcome by this innate sense of unease that often occurred when the late Irish singer-songwriter Sinéad O’Connor was brought up in conversation. My feelings weren’t really connected to anything O’Connor had personally done or even based on my opinion of her music, which I hadn’t heard much of at that point but I did like. No, instead O’Connor vicariously made me uncomfortable because of how the world reacted to women like her. They were stereotyped as difficult, uncompromising, complex women, whose unconventional lifestyles and unfiltered opinions made them constant targets. My teenage reactions to O’Connor weren’t because I agreed with how society viewed her, but rather because the judgement she and others like her received demonstrated how little society cared about women.

O’Connor was an iconoclast whose voice could switch between sounding akin to a lilting siren call and then transform into the primal wail of a woman scorned. In any case, her voice was always mesmerising. Her inarguable talent and enthralling personality granted her everything she needed to become famous, a fate sealed following her worldwide hit in the career defining 1990 single ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’. Despite O’Connor’s musical gifts, for much of her career she was more well known for being too much. She was too controversial, too divisive, the person people roll their eyes at when they talk. Her most gossiped about ordeal occurred in 1992 during a performance on Saturday Night Live in which she ripped up a picture of Pope John Paul II to protest child abuse in the Catholic church. Her appearance was met with anger, celebrities like Joe Pesci threated to attack her, and her career in the US was practically destroyed.

Recently her life has been re-evaluated following her untimely passing in 2023. In scores of obituaries, her friends, contemporaries, and fans of her work have all tried to summarise who Sinéad O’Connor was. Now in death she has been commended for her rebellious spirit, her bravery in talking about child sex abuse, and her wickedly sharp sense of humour. Although her life was now given more context than merely the flurry of controversies she had previously been defined by, much of the writing about her felt like her memory had been flattened, removing all of the sharp edges and contradictions that were a huge part of who she was.

Two recent books have tried to recontextualise O’Connor beyond the black and white depictions of her that have dominated media so far. The Real Sinéad O’Connor by Ariane Sherine attempts to present a thoroughly researched version of O’Connor’s life, plodding through each event in chronological order. Although Sherine uses archival research and new interviews to construct her narrative, the book is too factually rigid to truly delve deeper into O’Connor’s mindset. As a result of this approach, The Real Sinéad O’Connor never picks up the pace to become more than a straight forward document of O’Connor’s whereabouts over the years.

In contrast to Sherine’s mundane narrative, another new book on her life, Sinéad O’Connor: The Last Interview, released by Melville House Publishing, is alive with O’Connor’s caustic humour, the troubles that haunted her throughout her life, and her unwavering and deeply held beliefs. They can be seen precisely because the book is made up solely of interviews with the singer beginning at the start of her career in 1986 and ending with a transcript of her appearance on the American talk show The View in 2021, two years before she died.

There is no external analysis that expands on her words or a modern day recontextualization of how the media treated her back then, though the book is made all the more enlightening through a thoughtful introduction by musician Kristin Hersh, written from one misunderstood female musician to another. Sinéad O’Connor: The Last Interview works best as a document that traces the changing attitudes to O’Connor over time and her consistent and steadfast views. In one of her earliest interviews in 1986 with The Irish Times, she defiantly laid out why she shaved her head and why she would continue to, telling journalist Kate Holmquist, “I have the haircut because it makes me feel clear; it makes me feel good. I like to say, ‘I’m not a man or a woman – I’m Sinéad O’Connor’.”

O’Connor could be provocative – either because she truly wanted to shock people into waking up to some inherent horror that she couldn’t believe was still occurring, or because she simply just wanted to be cheeky. In a 1998 interview with NME, she finds time to both slag off the British pop scene in the late 80s, while also rightly calling out the racist programming on MTV that rarely played videos by Black artists. These opinions were endless and given frequently, but she stressed that the negative reactions were never her intention. “I don’t do anything in order to cause trouble. It just so happens that what I do naturally causes trouble … I’m proud to be a troublemaker.”

In response to the many reports about her opinionated nature, journalists began to expect to see a bolshy, loud mouthed confident young woman walk through their door during interviews with her. Instead, they got a sweet, empathetic young woman who struggled to find confidence in herself as the world continued to punish her for speaking the truth. She went into herself for a long time. She was aware that the derailment of her career after her fateful SNL appearance was positive in some ways as it removed her from the path of mainstream pop star back to protest singer where she always felt she belonged. It is also clear though that she was never able to reconcile with how she was treated, telling host Jody Denburg on KUTX 98.9 Radio that, she faced a lot of prejudice for her fame and “that can really cause a lot of self-esteem problems”.

From the many interviews I’ve read about O’Connor, pity is not an emotion she would have wanted to elicit from others. For this reason, it feels almost disrespectful to focus on her problems, but they were an essential part of her make up. She was troubled, for sure, but she was also gregarious, inquisitive, challenging, and was always in search of spiritual growth (visible in her constant search for the right religion). Reminding ourselves of her inherent mercurial nature is probably the best way to offset the need to only view her through her mistakes and controversies. It is important that her activist legacy is documented for younger artists to model themselves on, but it is also key that the whole of her is seen too. After a lifetime of being restricted to a one-dimensional portrayal, it is only right in death that she can be remembered for the fully rounded person she was; with her flaws, her tears, and her once in a generation talent and all.

The Real Sinéad O’Connor by Ariane Sherine is published by Pen & Sword. Sinéad O’Connor: The Last Interview is published by Melville House