Amongst dangling chains and pink-lit tiling, a man appears. He’s bare-chested save for a leather waistcoat which, combined with the latex gimp mask he’s sporting, gives him the same air of nocturnal menace as ‘Machine’, the bloodthirsty on-screen killer in Nic Cage’s snuff film whodunnit, 8mm. This man is Richie Culver AKA Quiet Husband.

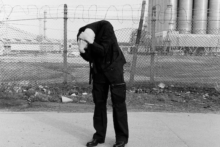

Culver’s work is brutish. It gets in your face. It’s also self-deprecating, art-world-skewering, and deeply concerned with labour, mental health, and self-medication. The artwork for last month’s Nerve Grid CD, for example, features a realistic recreation of racked white lines chopped across the clear casing. He’s a multidisciplinary artist utilising painting and photography, harsh noise, rampant techno, and performance. You’re as likely to experience his work in a salacious club as you are a gallery. Particularly if you’re in Berlin.

His creations unspool joy from the mundanity of suffering and depictions of disappointment. Some of his work deliberately rubs the right people up the wrong way. Not least the deceptively simple pieces that feature bare slogans dashed across white space in slopped black paint. Phrases such as “Birth Death” and “Tell all your rich friends about my art”. His music has been released by Industrial Coast, Deathbed Tapes, and Total Black, labels with a history for challenging and compelling music, and he has worked with envelope-obliterating artists like billy woods, Michael J Blood, and Salford drill powerhouse, Blackhaine, with whom he memorably intertwined noise and ranted word on the Did U Cum Yet? 12”.

Culver creates like someone’s swapped the sand in the hourglass of his life for piss-weak lemonade. By my count, he’s put out at least six musical releases this year and who knows how many other pieces of art. It’s enough to make you worried that he knows something we don’t. And with a backdrop of global conflict and climate change, maybe he’s just reacting responsibly to the comfort blanket of cognitive dissonance that warms our chills.

Religious Equipment takes us on a pain-strewn journey from birth to death. The gaping void spanning those two events are filled, here, with a mixed, yet tonally focused, cornucopia of artistic expression. Desperate hedonism tips towards nihilism. There are waves of aggressive distortion which obliterate everything, muddying waters and sandblasting minds, and there’s a sort of pathetic hilarity, primarily on third track ‘Klonopin’ which features a recording of two people discussing the importance of health and family. I say discussing, it’s actually a stonewall back and forth with one evangelising, in a desperately sad tone, that “being healthy is the best thing in your life” whilst their gruff interrogator roughly retorts “what else?”. The frail melody in the former’s jaunty hopelessness just makes it seem all the more pitiful. Culver’s framing of this tired grin-and-bear-it resignation is both heartbreaking and widely relatable.

He wastes no time. This tears out of the blocks with apocalyptic bass kicks, squealing feedback, and the sort of explosive thrust used to launch dogs into space. Beneath the obnoxious belligerence of ‘Methadone’, clamouring voices chatter and howl, like The Body losing arguments out of earshot. The album is bookended by the thumping of kick drums and ear-rasping drones. Closer ‘Buprenorphine’ feels like it’s building to something but, instead, drops the thick sounds out in favour of a forgetful breeze and the clank of a gravedigger’s shovel on stone-strewn soil. Like the comedian John Kearns says, “that’s life”.

Between hurried nascence and keeling over, lies the pandemonium we dare call existence. The track titles might have caught your eye. Each one named after an opiate blocker or narcotic substitute. If you’ve tangled with these yourself or know people that have, you’ll likely be aware of a common arc: continued dependence on drugs intended to halt intrusive feelings can leave users carved hollow, numb, a shell of who they once were. This blissful neutrality may, in time, develop into a millstone around their neck, its once safe embrace now become the thing to escape. And with that comes the whirlpool of withdrawal and uncertain steps back into a previously treacherous headspace.

Religious Equipment documents the chaos, the euphoria (no matter how brief), the bewilderment, tedium, struggle, and oppression of this experience. The harsh noises in his sound palette might appear confrontational and jarring yet there’s a surprisingly soothing element to the hail of distortion. Harsh Noise Wall, as peddled by the likes of Vomir and Fleshlicker, can act much like the benzos of the track titles and quieten tumultuous minds. White noise apps can also provide this experience for those looking to drown external and internal interferences. You only need glance at Jodie Foster’s character in the most recent series of True Detective to find an example of this roaring its way into the mainstream.

Whilst these calming effects are hinted at within the tracks on Religious Equipment, Culver’s insistence on underlying propulsion means that they often give a sense of palpitating anxiety. Even the sizzling beatless cadence of ‘Naltrexone’ embeds itself into your brain like looping intrusive thoughts as it sweeps through an unequalised spectrum, the frequencies shifting and manipulated. Fuzz compressed and applied.

From there he ploughs deeper still, switching from Armageddon beats into straight up harsh noise discombobulation. Feedback loops and high gain trouble courses by as if a burning raft steered by immolated gremlins. This sonic bristling levels out for a while before the ear-piercing singsong of high pitch feedback slices back through a barrage of rolling magma. He paints as thickly with distortion as he daubs black shades on pale canvases. This comes to a head on ‘Temazepam’ with its “If you cry” sample repeatedly fried into oblivion. Cranking the gain and flattening the words creates a tremendous oppressive sound that sucks all air out of the space between ears and speakers until there’s only pure pressure forcing your eardrums back and forth in a caustic blaze. In one fell swoop, Culver simultaneously mimics the unbearable experience from which fleeing seems so crucial and prescribes a fitting, aurally ingestible, remedy.