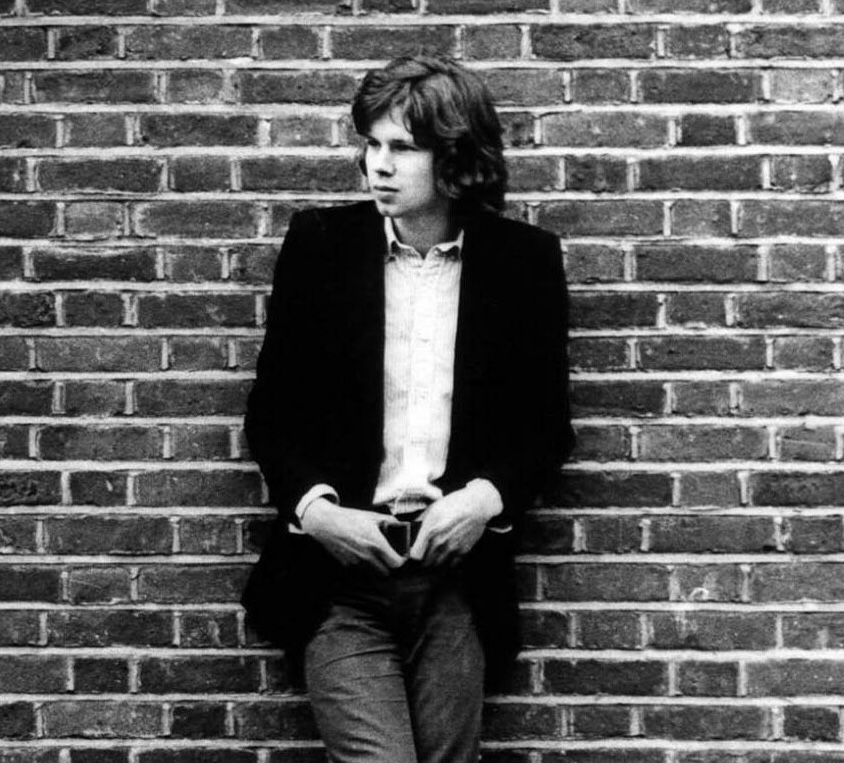

50 years ago, in the early hours of 25 November 1974, Nick Drake died by suicide, a sad anniversary will no doubt be commemorated extensively in media new and old. Those who knew Drake and musicians who were touched or influenced by his music will be solicited for a quote. Drake ‘experts’ will file their 1,500 words and they will all say pretty much the same thing. It will be by and large a tick box exercise in repeating what by now is a well-established party line in which his reclusiveness will cast an all-encompassing pall over his life and work. Someone will mention how they were once in a room with Drake, and he said nothing. There will be general agreement about the beauty of those three Island albums. And that will be it. No new light will be cast. There will be no fresh insight into the music.

That’s the trouble with the Drake story. Everything written about him has become predictable and terribly on message. Devotees seem to have settled for a fixed narrative which freeze frames the legacy and preserves the musical output in aspic. With Drake, the received wisdom now comes wrapped in a certain ‘don’t touch’ preciousness that does him, the flesh and blood artist, a considerable disservice. It leaves little room for critical manoeuvre or original interpretation.

When I read these set in stone eulogies I ask myself, where is any sense of the ambitious young artist who honed his guitar skills to perfection, not by osmosis but by sheer perseverance and graft? Where is the shrewdly career-minded musician who actively sought out record company attention and approval? Where is the proactive young man who offered John Cale guidance on what to play on ‘Northern Sky’ and ‘Fly’? Where is the innovator who, as Joe Boyd once observed, sat in the studio prior to recording ‘Cello Song’ on his debut album and ran obsessively through the drone tones of that instrument until he heard what he wanted, something that Boyd always regretted not taping? Where is the fledgling songwriter who took as lyrical inspiration for Bryter Layter’s ‘One of These Things First’, not some wistful folkie epistle about self-identity but Smokey Robinson’s ‘The Way You Do The Things You Do’? And where is the normal young man who, as Richard Morton Jack’s 2023 Drake biography notes, wrote dreadful and earnest teenage poetry like the rest of us. (Sample line. “Forced, jerked rhythms and sweating eyes/Hysterical enjoyment and unnatural benevolence/How can man so delude himself?”)

I quite like this version of Nick Drake. It shows him to be human and not permanently floating on a gauze woven from his own ethereal spirit. I also like the fact that he was a flawed and inconsistent lyric writer, capable of following lines full of grace with some right old undergraduate clunkers. I particularly love the fact that he teamed up with arranger Robert Kirby while at Cambridge, a beery undergraduate who by all accounts was not averse to lighting his own farts. Such a fulfilling writing partnership doesn’t exactly hint at Drake the oh so precious shrinking violet, unable to get his ideas across to a cruel and uncaring world. It suggests a steely and determined young perfectionist, prepared to put in a shift. Yes, there’s sensitivity and fragility in abundance in those songs, but there’s also grit and self-assurance.

Unfortunately, this is not the Drake that most people like to hear about. Instead they fixate on the psychological malaise and black-eyed dog depression he ultimately succumbed to. Even Morton-Jack in a Spin magazine interview to promote his biography states unequivocally that “All aspects of his behaviour post-1969 have to be understood as figments of his illness”. It’s this overriding interpretation of Drake that troubles me the most. The malaise comes to overshadow the art, and the songs are subsequently seen as mere symptoms of that malaise, rather than what is more often than not, particularly in the later years, active resistance to it. No more is this evident than in the dominant readings of his final album Pink Moon, and the last five songs he recorded subsequent to that album in 1973 and 1974. Pink Moon is still seen as sparse and harrowing by some, which is partly how I viewed it when I bought it in its week of release in February 1972. I had just turned 17 then – and my age shaped that opinion. As the years have gone by, Pink Moon has swelled in substance and significance. It is abundant in mature lyrical insight, some of it, yes, foreboding and bleak, but much of it blessed with wisdom and barbed wit. This applies to ‘Black Eyed Dog’, a song now almost entirely reduced by most critics to a literal statement on Drake’s own all-consuming debilitation. That’s not what I hear. I hear a great white blues song, sung in a great white blues voice with uncanny echoes of Canned Heat’s Blind Al Wilson. To me ‘Black Eyed Dog’ is up there with Peter Green’s ‘Man Of The World’ in the raw confessional stakes. But such a reading is not going to get me a seat at a critical high table. Much easier to go with the orthodoxy and make ‘Black Eyed Dog’ a mere conduit for the malady, as if Drake in his final creative flourish is capable of nothing more than channelling his depression into harrowing song.

I find this whole ‘the artistic output as a mere reflection of the condition’ argument highly problematic. It’s a curious inversion of the ‘winners write history’ discourse. No one reduces John Lennon to his ‘lost weekend’ or Bowie to his coke-addled years, but of course both men survived those incidents. If you succumb like Nick did, you get your history written for you, your art reduced to fatalism, and your day to day existence reduced to mythology.

A further insidious aspect of this critical reductionism is the appropriation of Drake’s music purely as trouble cure and palliative. We all use music as sanctuary and solace and I’m not knocking that. Whatever gets you through the night is valuable. But with Drake nowadays it all comes as part of a wider cultural drift towards wellness that seems to have permeated all walks of artistic life. We hear it in BBC Radio 3, which now treats its daytime output as soothing balm and music to relax by, and creative writing workshops where the sole aim seems to be to find ‘yourself’. Personally, I’ve never ever listened to Drake’s music while wanting to make it about myself. It robs those songs of their agency and does a massive disservice to the beguiling mystery of a muse that codifies as much as it confesses. You have to lean in a little and do some work in order to figure it all out. I’m more than happy to make the effort. I don’t want those songs served up as if they were a self-help manual or part of some musical twelve step programme.

I suspect the trend began with what a friend of mine called the ‘indiefication’ of Nick Drake. This occurred gradually over a period of time during the 1980s and 1990s in which growing cultdom removed Drake from the bustling cross-cultural milieu of his folk, rock, jazz and blues apprenticeship and repositioned him somewhere between Belle & Sebastian and Virginia Astley. Then came the cover versions as a whole new generation of emboldened bedsit troubadours got stuck into the repertoire. Out went the mesmerizingly tricky chord progressions, the JS Bach signatures, the Gilberto Gil and Carlos Jobim inflected Bossa nova touches, the drone poem debt to North African music, and the unmistakable music room echo of his mother Molly’s Noel Coward influences. In came the all-purpose indie busker strum, the whiny keening, and the timorous boilerplate sensitivity.

And then the media cottoned on too. Suddenly you couldn’t turn on the telly (anything from Heartbeat to a Volkswagon ad) without hearing Drake’s whispery voice and increasingly familiar flourishes. Almost overnight he became the go-to incidental music in mainstream dramas if you wanted a bit of bucolic reflection. Pretty rapidly no panoramic sweep across the Cotswolds in Escape To The Country, or quick pan around the displays at the Chelsea Flower Show was complete without a bit of Nick Drake. Through sheer overuse the Delius drift of ‘River Man’ became as cliched as the use of Cinematic Orchestra or DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing were a decade or two ago. This process has only become worse in the age of the algorithm as he suffers being dropped into awful wellness-themed playlists along all sorts of lesser, often copyist, artists.

On 24 July this year Drake was honoured with a BBC Prom at the Royal Albert Hall, a fittingly hallowed environment for one whose orchestrations and rich tonality lend themselves readily to the canonical treatment that a Prom bestows. The results however were a mixed bunch, often for the reasons mentioned above. The most ho-hum contributions stuck to the official template, remaining faithful to Robert Kirby’s album arrangements and followed notation and score to the letter. There was a moment during ‘At The Chime Of A City Clock’, where the treatment was so ersatz that I thought what’s the point? You might just as well have played the record. By far the most fascinating moments were when artists and arrangers took liberties. Olivia Chaney in particular brought a whole new air of come-hither earthiness to ‘Hazy Jane I’. The impact was such that it made me muse on the considerable potential for other transformative takes on Drake’s music. What aspects of the latent sensuality that lies at the heart of ‘Northern Sky’ say, or ‘Which Will’, might be teased out by further genderfluid readings? Certainly, Chaney brought a refreshing urgency to the latter song which rescued it from philosophical meandering and placed it in the realm of actual choice. Well? Which will you choose then? Go on! Make a decision!

Similarly, with Chaney’s interpretations of ‘Time of No Reply’ and ‘Things Behind The Sun’ there was a touch of Anne Briggs assertiveness about it all that was a million miles from the wispy woo gossamer light lilt of the average Drake copyist. There is still so much that can be done with those songs and those melodies. Perhaps the most astounding moment of the Nick Drake Prom occurred right at the end where the orchestra played a full arrangement of ‘Horn’. The sparse three note figure instrumental of ‘Pink Moon’ was fleshed out to epic effect and the vast dome of the Albert Hall suddenly reverberated to harmonics that had more than a touch of Charles Ives and Moondog about them. There should be more of this. Such expanded tonality lies dormant and concealed within that wondrous music, just waiting to be liberated and let loose.

Meanwhile, on a Facebook fan page recently, a well-respected and equally neglected contemporary of Drake’s from the early 1970s folk scene popped up to mention in passing that he had once met Nick and spent a very pleasant few minutes chatting with him. There were a few initial ‘likes’ and warm comments of appreciation for this brief reminder of an earlier time when Nick Drake was still full of promise and unfulfilled potential. Just another hopeful in a city of hopefuls standing outside a folk club in the rain, having a natter with a fellow musician. Within a few exchanges everyone had brought the conversation back to Nick Drake’s mental health issues. Business as usual.

Rob Chapman is the author of Unsung : Unsaid: Syd And Nick In Absentia; his book can be purchased here