“How do you exist in a world that doesn’t line up with your moral code, but also doesn’t line up with any moral code?” asks Lee Buford.

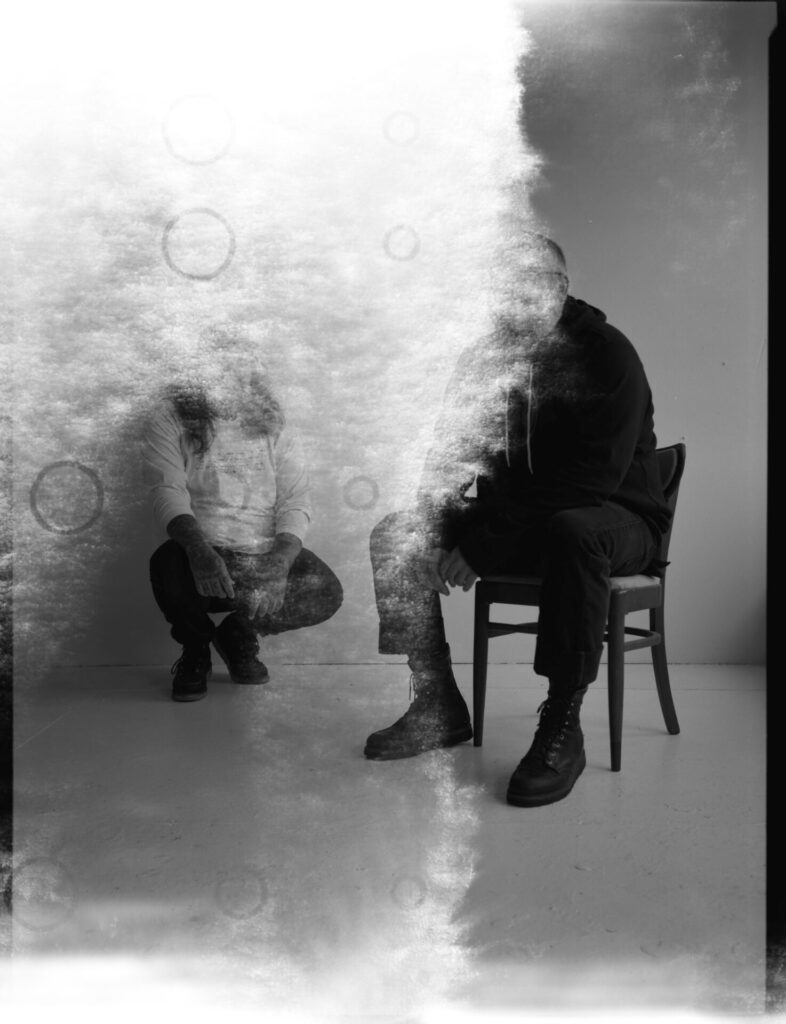

His band, The Body, is less a musical project than a coping mechanism. For a quarter of a century, Buford (electronics/percussion) and Chip King (guitar/vocals) have contended with a world that doesn’t share their values by blocking it out – or crushing it – with their music. Their sound traverses punk, doom metal, electronica and pure noise, endlessly layered and then moulded into their image. It exudes frustration and strives for empathy.

New album, The Crying Out Of Things, is an amalgamation of everything that’s come before it. The Body’s discography is vast, something it has in common with collaborators Thou. Often, Buford and King act as facilitators for others, alongside longtime producer Seth Manchester; they’ve also released collaborative records with Uniform, Big Brave and Full Of Hell among others. This is the second album they’ve released this year, after Orchards Of A Futile Heaven, with Dis Fig (who also features here, on ‘The Building’). The form the pair take is The Body, and its function is to foster community.

“I think it is, in a practical sense, good for us, because it does connect us to so many of our friends, in a musical way,” says Buford.

When I speak to Buford over Zoom, confusingly he is at King’s house in Portland, Oregon. Recently married, Buford has moved from Portland to Connecticut, which is just 40 minutes drive from where The Body records, at the Machines With Magnets studio in Providence, Rhode Island. King is on tour in Europe with Dis Fig. Buford doesn’t fly. He took an aeroplane once, when he was 14 years old, and the experience was enough for him to never want to do it again.

During the making of The Crying Out Of Things, which was before his move, Buford embarked on several four-day drives from Portland to Providence. The recording process was disjointed, but he thinks that played in its favour. Originally, The Body had intended to record with a choir as they did on their second album, All The Waters Of The Earth Turn To Blood. The process for that earlier record had been painstaking; they used so many overdubs it took them a year to finish it. For The Crying Out Of Things, however, they soon found themselves reverting to an established approach of starting with samples and building songs out of them. They then honed the sounds further, layering and layering once again. “I think it feels more like it’s a bunch of different stuff from all the albums smashed into one,” says Buford. “I think it’s more cohesive in that regard, but I also think it makes it pretty strange.”

On the dubby ‘Removal’, Buford sampled an MC yelling between songs at a 90s soundclash and went from there. Dub and reggae is a sonic meeting place where Buford, King and Manchester can all congregate. “Seth doesn’t listen to heavy music, and that’s why we get along with him so well, because we don’t really either,” says Buford. “We don’t really care about getting those kinds of sounds – of heavy metal.”

The spoken-word samples on the album open up something akin to what the lyric to ‘A Premonition’ describes as “a doorway into dark”. On ‘The Citadel Unconquered’, a disembodied male voice speaks of his feelings of detachment: “The truth is I’ve been in a bad way for a long time. Not wanting to do anything […] I had a wife and kids, they meant nothing to me. I have money – means nothing to me. I have life, that means nothing to me.”

The album’s essence of apparent hopelessness connects most strongly to 2014’s I Shall Die Here, produced by the Haxan Cloak. More metallic and straightforwardly bleak than The Crying Out of Things, at times it sounded outright suicidal. “If I go through with it I die, as I must at some point. If I don’t go through with it, my choice is essentially to suffer, and to inflict suffering on my family…” says the sampled voice on that album’s ‘Alone All The Way’. This smacks of what Nathaniel Hawthorne said of his last meeting with Herman Melville, who set the opening of Moby-Dick in the port town of New Bedford, itself now 40 minutes drive from Machines With Magnets: “[he] informed me that he had ‘pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated.’”

The decade that’s passed since I Shall Die Here has seen a shift in The Body’s perspective. They have moved through what Buford calls “a nihilism that was forced on us” by living in the modern world. In 2010, they told tQ that civilisation was “doomed to utter failure”. But eschatological ennui is exhausting. And recognising that life is something we walk through together has helped.

“I think that’s always been a thing we’ve had, where there is a lot of frustration [that comes with] living life in a meaningful way and a good way,” says Buford. “And in doing that, the hardships of personally what you go through, and what the world goes through. It’s tough being alive and bearing witness to how the world works and not having it affect you, if you have any empathy towards life in general.”

One of The Body’s t-shirts depicts a Christian cross with a shroud draped over it and a skull on the ground alongside; Jesus is absent at his own crucifixion. “I am tired of this world,” reads the t-shirt’s slogan. The use of Christian imagery, here and elsewhere amid the band’s output, reflects the hypocrisy of moralising religious authority figures. “This is the world they created,” Buford says of the major religions. “But [they] can’t even abide by… just the human decency of what [they’ve] even created. And I think that’s where the frustration comes through.”

As we speak, I notice a small framed photograph of downtown Manhattan at night hanging behind Buford, taken before the destruction of the twin towers of the World Trade Center. It feels like a miniature portal to a world about to come down, and evokes the continual irruptions challenging its worldview that the West has withstood since. As much as The Body plough into such ideas thematically, they also do it musically. ‘Careless And Worn’ sounds like a song exploding out of itself. After repeated listens, you pick through the ruins created by its blown-out beat to find the vestiges of precious melody, even if they are see-sawing, funereal horns.

Buford grew up in the 80s, drawn to the dark musicality of The Cure and Depeche Mode. Now, when he listens to pop music, it tends to be “sonically complex”, like The Beach Boys. Even though it’s very listenable, there’s a lot happening. For him, The Body is a “dumbed down” version of that.

King spent the early 2000s playing alongside Sleep ripoffs in the stoner rock scene and got thoroughly burnt out on guitar riffs. Buford thinks this explains King’s tendency to “bury the melody as much as he can”.

“I mean, not just in the doom/stoner scene,” adds King over email from the tour with Dis Fig. “The repetitive riff-to-riff format got pretty old in a lot of guitar-centred music. But so many bands just seemed only to look backwards and based the entirety of their sound on one of four or five records from the 70s and 80s.”

The Body believes the world isn’t an easy place, and that music shouldn’t be easy either. The Body is keeping the score. When a naked, sonorous guitar rings out on album closer ‘All Worries’, it feels like a reward for making it this far. Stripped of the sonic ferocity elsewhere, it allows for other, insidious horrors to seep in, with its sampled chanting and King’s screeching electro-howl of a vocal: “the weariness of the horror/the awareness of complicity”.

The genocide in Gaza hangs over The Crying Out Of Things like an immense shadow, where “flames reflect on the low cloud” (‘A Premonition’). As ‘Removal’ puts it: “whither shall you wander/when your home is levelled”. Whereas the apocalypse is forever delayed in the West (appearing in flashes), it is ongoing in the Middle East.

Buford says that the Israeli treatment of Palestinians has been “a big sticking point” for The Body for years, turning down gigs in Israel as far back as 15 years ago. For him, the plight of the Palestinian people is “a perfect example of how the world can pick and choose what lives matter”.

“I remember right after 7 October, I was like, I feel like I’m going crazy,” says Buford. “It’s like Palestine didn’t exist until 7 October, and to not put things in any sort of context, honestly, I was like, I feel like I’m going insane. Because people I like, even respect, [were] acting like this [is a] crazy thing, and they’re so surprised it happened. And it’s kind of insane to not think that this would be the end result of life over there.”

King tells me that the lyrics were actually written before the current conflict erupted. “But they are about the conditions that have led to this ongoing nightmare that the Israeli regime and the United States are perpetuating, not only in Gaza and the rest of Palestine, but all over the region,” he writes. “They are about Sudan, about the Congo, about Cuba. About everywhere. The wealthy and powerful create instability as much as possible in order to leverage conditions to keep raw materials as cheap as they can. All to the detriment of the majority of the world. I feel like I have much more in common with a cobalt miner in central Africa than a fucking billionaire, even though our situations are greatly different.”

Perhaps this album could have been called The Carrying On Of Things. The most uncomfortable emotional truth of The Body’s music seems to pivot on a couplet from ‘The Building’: “wringing hands in worry/is nothing”. That “nothing” could mean that hand-wringing is inadequate in the face of humanity’s suffering. Or that it’s the very least one can do. Or that it’s meaningless.

“I don’t think there is a moral code applicable to the world at large,” says King. “The disparity in conditions between all of us speaks to that […] All the consolidated wealth and power in the world is bleeding the working people and poor and disenfranchised of us all dry. The disappearance of a highly consumer middle class is destroying the illusion that success of any kind is possible. Of course, this is mainly the United States that I know, but since we export all the worst parts of our culture worldwide, I wouldn’t expect things to really get better. We believe in things like fairness and justice and equality, but most evidence I see points [to the fact] that those things don’t really exist unless you can afford them, which sadly most of us can not.”

The Body seeks out catharsis through connection. Buford points out that the only tour they’ve taken which wasn’t with one or more of their significant network of friends was with post-black metal act Alcest. That network is a who’s who of innovators in sonic extremity, from Uniform to Full of Hell to Big Brave to Kristin Hayter. It’s simple: working with their friends helps them feel better.

But how would they like us to feel after listening to this new album?

“Ideally, I would like it if everyone who listened would give me a little kiss on the forehead,” says King, “arm themselves and then hand-in-hand we tear down every border, foundation and artifice of wealth-centric human culture.”

The Body’s new album The Crying Out Of Things is out now via Thrill Jockey