“There is nowhere to turn, but to yourself,” said Dory Previn. “Instead of repeating, I’ve come to myself.” In late 1969 the three times Oscar-nominated lyricist, and sometime chorus dancer, experienced a public breakdown on a jumbo jet parked on a runway, and pulled off her clothes in the seats, a reaction against a cataclysmic event in her personal life – her husband having an affair with her friend, a romance she found out about from the newspapers. Ejected from the plane, she was committed to an asylum. It wasn’t her first visit, yet this moment marked the beginning of a rejuvenated version of the artist – this middle-aged woman emerged from the crisis with a new set of songs written in therapy, and for the next seven years Previn would record seven albums’ worth of acerbic, spiteful, exhilarating and often heartbreaking material, songs so elegantly crafted that they easily stand alongside some of the most revered female musicians of the era, such as Carole King, Carly Simon and Joni Mitchell. Although highly regarded for her soundtrack work, her solo legacy runs through contemporary acts such as Tindersticks, Ren Harvieu, Fat White Family and Jarvis Cocker. Previn is still relevant, but until now, has remained firmly in the ‘cult’ camp.

A long overdue documentary, Dory Previn: On My Way To Where, explores her life and work, hopes and fears, and revisits that day on the runway with clarity and conviction, expanding on what came before and after – focusing on her diaries (read by Succession’s J. Smith-Cameron), lyrics and interviews in a way that allows the subject to speak. Previn’s own view of her mental health is sensitively rendered, encompassing her various points of disintegration, upheaval and renewal. Her relationship with three imaginary characters throughout her schizophrenic episodes is handled with care. For Previn, this alternative reality was just as important as ‘real life,’ and over time, she made friends with them, using them as guiding symbols. They are illustrated by animation in the film, but this does not feel trite or sickly in any respect, merely a tender representation of the affection she felt towards ‘Mama’, ‘Max’ and ‘The Lion.’ Using archival footage, songs and recollections of those who knew her, this illuminating portrait weaves together the interior and exterior life, giving a compelling account of the artist’s creative impetus. As an introduction to her work, it captures the rare essence of one of the most underrated singer-songwriters of her time, who believed: “There is no war like the internal war of the psyche.”

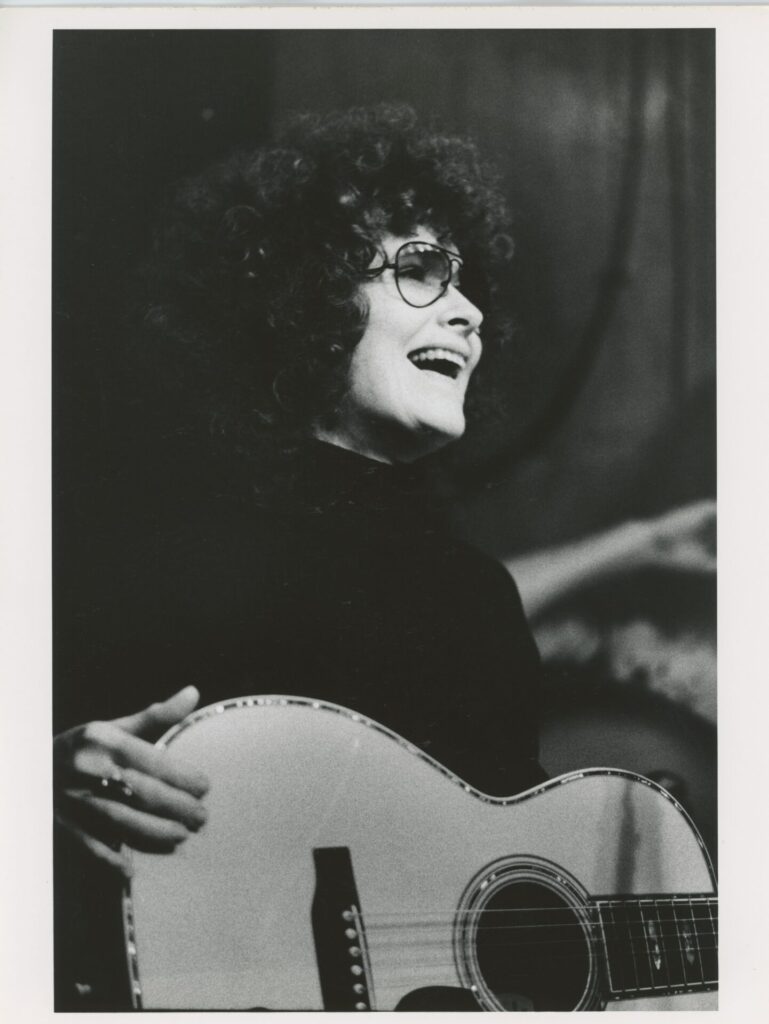

Born into an Irish Catholic family at midnight in Rahway, New Jersey, on 22 October, 1925, Dorothy Veronica Langan’s personality would be forever divided according to superstition. “I was twice born,” she wrote in her autobiography, Midnight Baby. A left-handed child who was forced to use the right, she was told it was another affliction, or “Satan’s special mark”. It was in her formative years, that her father – who had been gassed digging trenches in World War One – became convinced his daughter was not his own due to doctors telling him the gas attack could render him infertile. His paranoia about his eldest child (who clearly resembled him, with red curly hair and freckles) resulted in her trying hard to win his attention, her singing and dancing the only way in which she could form a bond with him. “I danced to please him,” she told the BBC. “It was known I would not have an education, the only place the poor could go without one was into showbiz. You didn’t need credentials.”

During childhood, Dory witnessed her father’s unravelling. “When the devil’s in him, he’s not responsible,” her mother would say, explaining his violent behaviour as shellshock. The most traumatic moment came when he locked the family in the dining room and held them at gunpoint for four months, not allowing them to leave until a priest had him committed to an asylum. It eventually provided grist to the lyrical mill, the shattered assumption resulting in the perniciously brilliant ‘With My Daddy In The Attic’ many years later. For Previn, it was essential to keep the music palatable and light, so she could deliver the darkness through her lyrics, catching listeners unaware, forcing them to play it again to make sure they really did hear those lines: “with his / madness on the nightstand / placed beside / his loaded gun / in the terrifying nearness / of his eyes.” These are words that would not be out of place in verse by Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, or Sylvia Plath, such is their innate power.

Growing up, Previn was schooled in the Irish folk tradition but was also enamoured with country and western (the music her father adored), and French chansons. There was scant exposure to literature, until she met a struggling actor, who gave her books by Gertrude Stein and James Joyce. “I immediately understood them,” she said, “I had no preconceptions.” Both writers gave her impetus to begin writing lyrics, and within four months of writing the first, she was under contract at MGM. In many respects she was a child of Modernism, applying a raw literary approach to mainstream culture. Previn’s talent for writing was spotted early on by Arthur Freed (writer of Singin’ In The Rain and Gigi), at the time she was a jobbing actor living on canned beans and was surprised to be offered a job. At MGM she met André Previn, becoming his writing partner. Her stage name was Dory Langdon, not Langan. Her family were “Bogtrotters” from New Jersey and came from poverty. He was a Jewish Berliner and highly trained music scholar from a young age. Together, they formed a hugely successful partnership – writing soundtracks for Valley Of The Dolls, Inside Daisy Clover, and John Lennon’s favourite musical, Goodbye Charlie, which The Beatles sang together in a blissful haze, floating down the Ganges with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Harold Arlen, who co-wrote ‘So Long, Big Time!’ with her, once noted of her talent: “She knew how to write pain.”

According to Previn, those years were essential to the writer she eventually became, where she learned how to craft a song. Yet after her breakdown, she learned how to write in a different way, reprogramming herself, using the palatable aspects of traditional melodies (with arrangements reminiscent of Van Dyke Parks) combined with some of the most devastating lyrics of their time. Hilariously funny in places (and written in lowercase) such as: “mine was a bloodless death / not grim and gory / more like ali mcgraw’s / new enzyme detergent demise / in ‘love story'”, her words also had the capacity for an unsurpassed depth and poignancy, as displayed in her poem, ‘Broken Soul’: “you will become entangled / in the simultaneous vision / of sea floors / and far stars / one eye pointed up and out / the other pointed down and in / and your / self / groping stunned and unbalanced / between the two.”

It was, however, her relationship with André Previn that proved to be the catalyst and detonator of the second period of her career. Following a ten-year marriage, the partnership entered rocky terrain, with her admitting: “I don’t know how he stayed so long; he left me for another woman after I had left him for another reality.” When the actor Mia Farrow entered the equation, via a visiting Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate, she observed of the interloper, “the skin was translucent, as if she were wrapped in the gauze of a placenta.” The two became friends, with Previn confiding how terrified she was of flying, and how she was afraid her husband would leave her, thus opening the door for her new friend to fly to Europe and pay her husband a visit.

Describing her condition as ‘madness-sadness’, there was always a part of her observing and remembering whatever chaos was playing out in the other part of her life. While undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy, her condition no doubt exacerbated by the Farrow saga, she wrote ‘Beware Of Young Girls’, her devastating attack on the waif: ‘She was my friend / she sent us little silver gifts / oh what a rare / and happy pair / she / inevitably said / as she glanced / at my unmade bed.”

Following her clinical discharge, musical collaborators were reluctant to take on her songs, believing Previn, now in her 40s, to be too old to market as a ‘fresh product’, and finding the lyrical content too candid and disturbing. At this point she decided to write the music herself, enlisting Nick Venet (former producer of the Beach Boys, King Curtis and Stan Getz amongst many other luminaries) to assist with her vision. Her explicitness was seen as detrimental by many in the music industry, but to others, her honesty was catnip. Personally, there was no regret for the path she chose. “I hate secrecy,” she once said. “If you keep it in, it festers.”

Writing from her home in Laurel Canyon, and touring infrequently, she was a prolific but reluctant performer, and finally gained a new sense of self through her work, remarking: “I suffered myself back to life.” Her reason for writing was not for fame or money, it was simply a creative impulse that she could not turn off, an obsessive and compulsive act. She had a devoted fanbase, many who came from feminist consciousness-raising networks and considered her a hero, believing her to be speaking the truth about womanhood, a history that could be traced back to her 1961 song, ‘Control Yourself’, where she sardonically observed, “always let tranquillity be your goal.”

In her later years, she married the actor Joby Baker, moved to the country, wrote a series of books and plays, renewed her friendship with André, became an anti-nuclear war campaigner, and lectured at American universities.

As noted by the filmmakers of On My Way to Where, there have been several acclaimed documentaries about overlooked women musicians recently: Karen Dalton, Judee Sill and Fanny. Unlike some of those narratives, there is no addiction or early death (unless the death of the self can be considered) in Previn’s life, and she was still productive well into her 80s. In the current climate of conversations in the music industry about mental health, her experiences provide some context and light for how female artists can seek a fulfilled creative life against the odds. This insightful film reveals how she learned to live with voices in her head, despite societal and institutional pressure to ignore them.

When her eyesight failed, Previn continued to write songs, including her final recorded album Planet Blue, which she released for free distribution in 2003, with the closing lines: “I’m going away, I heard her say / I’m going away, won’t someone say goodbye…”