There are performances that rewire your brain chemistry, forcing you to listen to music and sound in different ways. Roscoe Mitchell’s solo set at the Jeff Mangum curated All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in 2012 was one such performance. At the time, I was familiar with some of the composer and multi-instrumentalist’s work with the Art Ensemble Of Chicago, but I’d yet to hear his unaccompanied solo recordings. I’d experienced some masterful solo saxophone sets before – Evan Parker channelling torrents of tone, John Butcher manipulating feedback, Masayoshi Urabe howling into the void – but Mitchell brought a singular intensity and rigour to Minehead that chilly March day.

Alternating between alto and soprano saxophones and recorder, Mitchell worked through his musical language, spinning short phrases into extended forms. In my review of the festival, I praised Mitchell’s use of circular breathing to “conjure long, exhilarating streams of sound… tight microtonal clusters and freewheeling derives, ascending scalar runs which are punctuated by rude blasts or burn up in a jet of rasping multiphonics.” It was a long way from the fire-breathing expressionism that had first attracted me to free jazz, but just as transporting. There’s something genuinely psychedelic about Mitchell’s stretching of time and space, his epic bouts of circular breathing, the sheer strangeness of his sounds. Tones fold in on themselves, double and triple, forming teeming layers of sound. That one person could create such a polyphony was mind-boggling. By the end I was levitating; Mitchell had taken me somewhere.

Twelve years and several live encounters with the great man later, I still get that same thrill from listening to Mitchell’s solo recordings, not least the famous 22-minute version of ‘Nonaah’ from the 1976 Willisau Jazz Festival, where the saxophonist pulls the initially hostile audience into his sound world. That composition, with its jagged rhythms and intervallic leaps across the alto saxophone’s range, has become Mitchell’s signature piece, reworked for various configurations and reinterpreted by numerous others, including the brilliant Darius Jones on his 2021 solo outing Raw Demoon Alchemy (A Lone Operation). Two succinct versions bookend The Solo Saxophone Concerts, the classic album gathering live performances from 1973 and 1974 (confusingly, the album was reissued in 2009 as The Solo Saxophone Concert). While he’d recorded solo pieces for previous releases, this was Mitchell’s first solo saxophone album. Alongside Anthony Braxton’s For Alto (the first ever solo saxophone album, recorded 1969, released 1971), it’s a foundational text in the solo saxophone canon. As the saxophonist Ken Vandermark writes, “both of these sets of material lay the foundation for a collection of independent vocabulary and grammar that each musician has continued to develop for decades.”

As members of the pioneering Chicago musicians’ collective the Association For The Advancement Of Creative Musicians (AACM), Mitchell and Braxton had been encouraged by co-founder Muhal Richard Abrams to develop original approaches to composition and improvisation, drawing freely from jazz, blues, pop, folk and modern classical. Unaccompanied solo performance was an arena in which AACM members could experiment with new vocabularies and in 1967, Abrams challenged his mentees to perform solo concerts. As a result, solo playing became central to the musical practice of several AACM figures, including Mitchell’s comrades in the nascent Art Ensemble Of Chicago, trumpeter Lester Bowie and bassist Malachi Favors.

Braxton’s experience of these solo concerts famously led to the development of his Language Music concept. Finding that he had run through all his ideas after ten minutes of solo improvisation, Braxton set about cataloguing musical elements (long tones, short attacks, trills, multiphonics etc) which could form the basis of scores and improvisations. For Alto is an early example of this approach, one which he has continued to develop and refine throughout his career. In parallel, Mitchell developed his own compositional system, based on transcriptions of his improvisations. As Abrams related to George Lewis in A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM And American Experimental Music: “My initial advice to Mitchell concerning composition was to ‘write down what you’re playing on your horn. He proceeded to do that – that’s where ‘Nonaah’ and stuff like that comes from – and he’s never looked back since.’ ”

In November 1967, Mitchell recorded a solo piece as part of the sessions that would eventually see light of day on 1975’s Old/Quartet. ‘Solo’ opens with a brief statement on alto saxophone, before Mitchell moves into a music-box melody for tuned percussion and tam-tam. There are short bursts of clarinet and harmonica, before a more sustained engagement with the material on saxophone and a reprise of the percussion theme. It’s a fascinating piece, building on the experiments of Mitchell’s 1966 debut Sound, while anticipating the multi-instrumentalism of the Art Ensemble. There’s a straight-up saxophone solo on 1968’s Congliptious, a transitional recording credited to the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble. Moving from delicate melodicism to overblowing and multiphonics, ‘Tkhke’ is a powerful statement of intent.

In 1968, Mitchell and his comrades moved their operations to France, settling on the collective name Art Ensemble Of Chicago. During their two years in Europe, the group recorded classic albums like A Jackson In Your House and People In Sorrow and collaborated with Fontella Bass and Brigitte Fontaine. Following his return to the US in 1971, Mitchell made a new home in Bath, Michigan, where he chartered the Creative Arts Collective, an organisation that shared many of the principles of the AACM. The relative isolation of his rural surroundings gave Mitchell the opportunity to “slow down and do a lot of composing.” Around the same time, as Sam Weinberg notes in his perceptive overview of Mitchell’s life in music for Sound American, Mitchell intensified his focus on solo composition and playing, leading to the US, Canadian and Finnish performances collected on The Roscoe Mitchell Solo Saxophone Concerts.

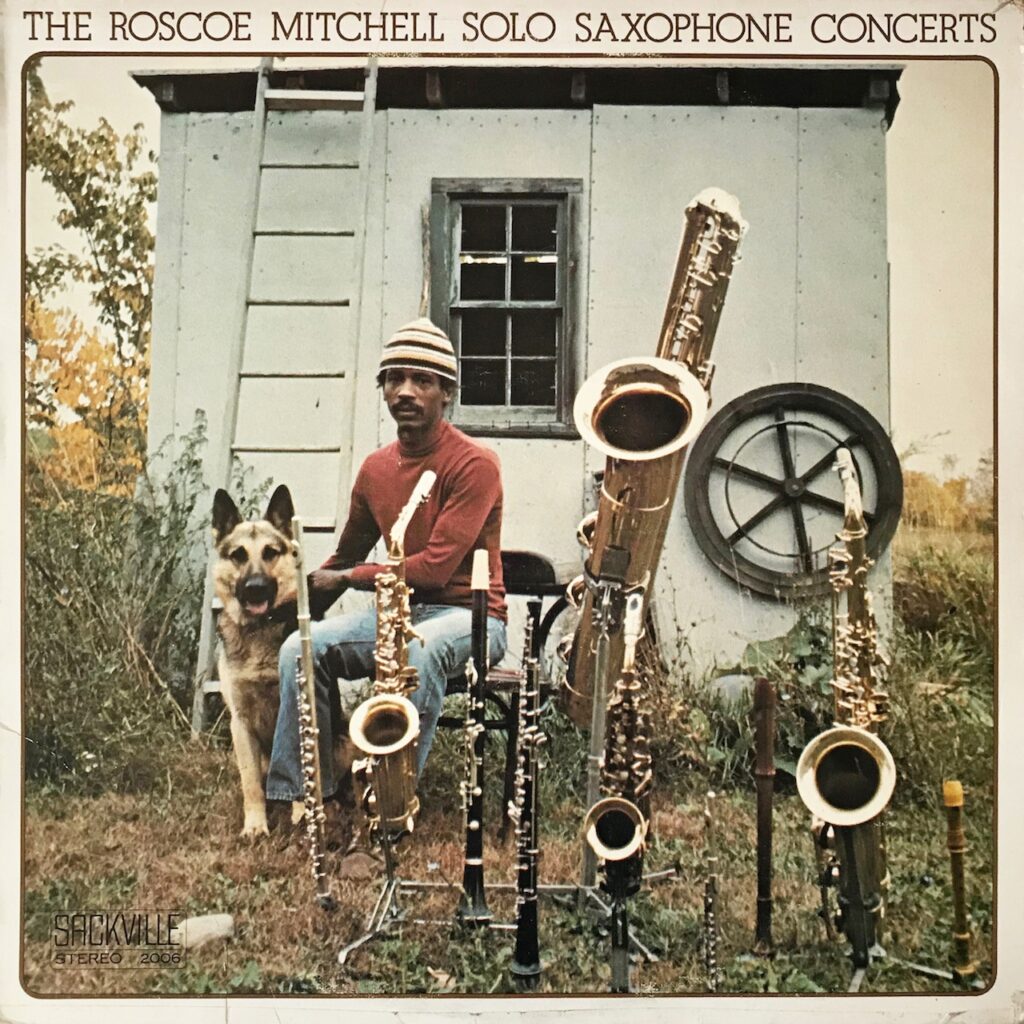

The famous album cover captures the musician’s world at the time. With his dog Io by his side, a casually hip Mitchell sits in his garden at Bath, surrounded by an array of wind instruments: saxophones, clarinet, oboe, recorder and flute. On the album itself, he plays soprano, alto, tenor and bass sax, his facility on each instrument remarkable. At this point, it’s worth acknowledging that solo saxophone, particularly in an avant-garde idiom, isn’t the most accessible format. There’s no rhythm section for the listener to hang onto, or the kind of interplay that animates most jazz and improvised music. The trick is to think of it as a dialogue between the soloist and their instrument.

The “practiced solo improvisations” of Solo Saxophone Concerts are stunning examples of this, with Mitchell working rigorously through compositional structures and instrumental techniques that he had honed over time. “The point of playing solo is to prove you can sustain a structure for longer and longer periods of time,” he explains, “so I develop exercises to increase my power of concentration, starting off with small sections at first, and while I’m doing that, I’m also working on technique – things like… breathing and fingering.”

There are few better examples of this than ‘Nonaah’. Composed in 1972, the piece made its first recorded appearance on the Art Ensemble’s incredible 1973 album Fanfare For The Warriors, the horn frontline presenting the jagged melody in counterpoint and unison, before guest pianist Muhal Richard Abrams takes it into a rhythm section feature. After a few minutes, the horns re-enter, improvising around elements of the written material. It’s an exhilarating performance, testament to the adaptability of Mitchell’s composition. As Mitchell put it in a recent interview, the piece is his “own system, a particular set of mathematics” with huge generative potential. Or as he wrote in the sleeve notes to the 1976 Nonaah, “once you put yourself in that atmosphere you can ride on forever.” The versions on Solo Saxophone Concerts are short and sharp, yet no less complex.

The first comes from a November 1973 performance in Montreal. Mitchell’s alto tone is characteristically taut and acerbic as he launches into the opening phrase with its wide scalar intervals and angular rhythms. The original score has no set tempo or bar lines, giving Mitchell the freedom to play with duration and pace. He takes it at a fair lick here, the peppery interplay of minims and triplets steadied by greasy honks. There’s something of the farmyard to the middle section, as Mitchell answers his squawking and clucking with hoarse brays. In the final moments, Mitchell rapidly ascends from gnarled roots to thin green shoots in the alto’s upper range. It’s all over in 70 seconds, a concentrated burst of radical sound. The polite smattering of applause that follows is in stark contrast to the exuberant clapping and stomping that opens the second version, recorded eight months later at the Pori Jazz festival in Finland. Mitchell takes that energy and runs with it, initially playing off the crowd’s rhythm before moulding it into his own elastic form. His articulation is sharper, the tone rugged, leaving the Finnish crowd thrilled.

Placing these versions at either end of the album is a smart move, establishing a narrative in which Mitchell’s bold experiments find their audience. It’s also a neat framing device to the longer pieces, which run between three to nine minutes, that make up the rest of the album. On Malachi Favors’ ‘Tutankamen’, Mitchell brings a rare sensitivity to the bass saxophone. He strolls through the bluesy melody at his own pace, anchoring the delicate mid-range phrases with warm bass tones that are more whale song than foghorn. Mitchell jumps between soprano and bass on ‘Oobina (Little Big Horn)’, his wobbly trills and gently probing tones punctuated with rude blasts on both horns played simultaneously. Rather than play it as an exercise in contrasts, Mitchell maintains a careful balance across the range of tones and timbres: it’s a delight to listen to.

The soprano gets its own moment on ‘Jibbana’, Mitchell filling the air with wispy staccato phrases and legato tones that curl at the end. As Mitchell tests the limits of the form, the notes curdle and strain, fluid licks coming and going in a flash. The two-part ‘Eeltwo’ is an arrestingly tender meditation for tenor saxophone, a susurrus carrying pre-bop jazz lyricism into the future. It’s a joy to experience Mitchell’s virtuosity across the horn family, but ‘Enlorfe’ and ‘Ttum’ underline that the alto is the truest representation of his idiosyncratic voice. A tribute to John Coltrane, ‘Enlorfe’ illustrates that the best way of honouring a master is to be original. With a hushed intensity, Mitchell maps out a new language for the alto saxophone, exploring a series of upper-range whelps, peeps and quivers. Every note is keenly considered, each small variation in timbre carrying considerable weight. It’s beautiful. ‘Ttum’ sits somewhere between the quietude of ‘Enlorfe’ and the angularity of ‘Nonaah’, pinched legato phrases curling upwards into scratchy tones. Mitchell punctuates all this with parps and honks, clucks and whorls, before breaking it all down to a pellucid melodic figure. It’s a disarmingly intimate moment, all the more affecting for its brevity. Tough, gnarled tones follow, yet Mitchell pulls back from all-out free blowing, continuing to mould the dynamics and timbre with remarkable control.

Mitchell might describe his solo music in mathematical terms, but its emotional impact shouldn’t be overlooked. There’s something deeply moving about hearing a great artist testing the very limits of technique and form to push into the unknown. Mitchell is a conductor of magic and chaos, seducing the open-minded listener with his spell. The Solo Saxophone Concerts might not be the easiest place to start with his music, but if you dig the Art Ensemble then you should jump in without hesitation. Mitchell maps out new constellations of sound, setting the standard for everything he’s done since, from solo epics to orchestral compositions. It’s a portal to one of the most significant musical minds of our time.