“People talk about hip hop like it’s some giant living in the hillside coming down to visit the townspeople… Me, you, everybody – we are hip hop.”

Mos Def – ‘Fear Not Of Man’

It’s the late 1990s and hip hop is the cultural and commercial juggernaut it always threatened to become – so vast it’s rendered everything else pretty much irrelevant. But the hip hop that’s dominating the charts, spraying everything platinum and ferrying magnums of Cristal to the velvet-roped VIP section… Well, it’s not the ‘Black CNN’ Chuck D promised us. It’s not the grimily psychedelic hyper-invention the RZA envisaged. And it’s not the super-vivid street poetry of the ‘Gangsta’ era, either – by spring of 1997, both Tupac and Biggie are dead.

No, by the time rap swells to the point where it is everything, hip hop is Sean ‘Puffy’ Combs witlessly half-inching hooks from pop hits you were already sick of and shoeing them in suspiciously funkless beats. Sean fucking Combs, selling you the dullest, most normcore aspirational fantasies. Sean fucking Combs, falling off his motorbike so he can weep some crocodile tears in a promo clip endlessly repeating on The Box. Sean fucking Combs somehow making even ‘Kashmir’ seem dull and, by extension, Godzilla too.

But pop abhors a vacuum, be that of funk, soul or personality. And while the Didmeister was living large, in the gutters of the Big Apple the fightback had begun, the rejection of what Mike Ladd described (on Infesticons’ album-long repudiation of this era, Gun Hill Road) as the “Jiggy man’s paradise”. “It was purist, avant-garde,” El-P of underground visionaries Company Flow (and, later, Run The Jewels) told me. “We weren’t fantasising about houses, cash or cars. We were fantasising about being dragons spitting flames out of our eyeballs.”

This scene of avant poets and footloose beat-conductors grew out of street corner cyphers and Boho coffee bars, flourished on self-released 12-inches and finally broke out into the world at large thanks, in no small part, to James Murdoch (son of Rupert and arguable inspiration for Kendall Roy) and his Rawkus Records. The imprint released key records by Company Flow, former Organized Konfusion luminary Pharoahe Monch and foul-mouthed ne’erdowell R.A. The Rugged Man, along with a slew of 12s from less-stellar (but no less essential) MCs. But the label’s landmark early release was Soundbombing, a smudgy and essential mixtape introduced by Da Beatminerz’ Evil Dee, compiling highlights from the nascent Rawkus catalogue alongside freestyles from its signings. No other record quite captures the chaotic promise of this embryonic New York underground. And no other artist on Soundbombing seemed as primed to rocket this underground to the overground than the mighty Mos Def.

He appears on four of the album’s 17 tracks, first surfacing on ‘Fortified Live’ by Reflection Eternal – vehicle for future Black Star partner Talib Kweli and producer Hi-Tek – celebrating himself as “the interplanetary illuminati” throwing “basement parties on the mothership”, then tag-teams with Kweli again on exuberant freestyle. Soundbombing then reran both sides of Mos’ debut 12-inch for the label, ‘Universal Magnetic’ and ‘If You Can Huh! You Can Hear’. The former opened with another Mos freestyle, so deep in the pocket he can convincingly mimic a skipping record without losing his groove. Then the main event, over hallucinatory electric piano shimmers, Mos using the second verse to place himself firmly within a creative line that includes Tenor Saw, Melle Mel, Richard Pryor and Stevie Wonder without ever letting it sound like an empty boast; as he reminded us, it was in his “chromosomes to rock microphones”.

The flipside was a loose, magical thing, Mos finding his flow over a loop from the Brian Auger Express’ 1974 live reading of ‘Maiden Voyage’. Here, he got spiritual, asking heavy questions like “if time is the asset / how you gonna spend it?” with a lightness, an everyday touch that evoked the soul of the Native Tongues. If Soundbombing lifted up the manhole to peep the magic thriving in New York’s hip hop gutters, in Mos Def it found an emcee looking to the stars.

He had charisma to burn. Born Dante Smith in Flatbush and raised in Bed-Stuy, he learned from his grandmother the self-discipline that would propel his early career as a child actor. Aged 14, he landed his first role in a TV movie; three years later, a regular spot in a short-lived sitcom; five years after that the job of playing Bill Cosby’s sidekick in detective drama The Cosby Mysteries. But it was hip hop that he loved. It delivered him revelations at machine-gun pace: ‘Planet Rock’; Kurtis Blow; Melle Mel. That last one lit a fire within Mos, “The first time I heard Melle Mel, he blew my mind,” he told me in 1999. “He wasn’t just an MC – he was communicating ideas, y’know? He was saying something.”

He began rapping as ‘Mos Def’ alongside younger brother Denard, AKA DCQ, in 1992. Two years later, he and DCQ enlisted schoolfriend Ces to form trio Urban Thermo Dynamics, cutting three 12-inches. Next, he resurfaced as a solo act with features on DJ Krush’s MiLIght, Da Bush Babees’ Gravity and De La Soul’s Stakes Is High (the aptly titled ‘Big Brother Beat’, which posited Mos as restless younger sibling to the Native Tongues posse), all released 1996.

Mos’ energy seemed limitless, his talent and personality magnetic. “I was a fan before I met him,” Talib Kweli told poet/podcaster Jessica Care Moore. “He was a local boy made good. He was definitely different.” Kweli remembered Mos as a blur of perpetual motion, always on his way to the next opportunity, but never able to resist the siren call of the microphone. “We’d be in Washington Square Park, which was a mecca of freestyling. He’d be on his way to an audition, he’d have a suit on, but he’d stop in the park and jump on the cypher.” Their friendship was forged at open-mic poetry nights and spoken word events, where their flow and interplay, forged on the concrete playgrounds of hip hop, always won out. When Rawkus offered Mos what Kweli considered a boggling amount of cash to record twelves for the label, Mos was quick to ensure the label also picked up Kweli. No man left behind.

Rawkus recognised what it had in Mos Def. Labelmates like Company Flow delivered the shock of the new, the hardest edge, but Mos Def humanised New York’s underground sound, tapping into hip hop history as he drew power from the spoken word scene, then insurgent via Marc Levin’s acclaimed 1998 movie Slam. There was a warmth to Mos, an everyday-guy vibe that was engaging, that allowed him to communicate rather than simply orate, that invited ears to listen. He eschewed the self-conscious difficultness that made many early Rawkus twelves so electrifying, but also guaranteed to remain the province of only the deepest heads. Mos sought to educate, to elucidate, but, most of all, to entertain.

His debut 12-inch was a modest masterpiece, but was only a shard of the story: he was vast, he contained multitudes. And this multifaceted quality marked Mos Def as a rapper built for the album format.

A year before Mos Def’s debut album hit the shelves, Rawkus released the first full-length from his collaborative project with Kweli. Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Blackstar was a fine showcase for this well-balanced partnership, Kweli all blunt edges and hard polemic and sharp syllables, Mos smoother, warmer, loose and irresistible; their yin and yang was impeccable. The record was rooted in Black history: Weldon Irvine, jazz stalwart, street mensch and lyricist on Nina Simone’s civil rights anthem ‘To Be Young, Gifted And Black’, played keys on opening gambit ‘Astrology (8th Light)’; lead single ‘Definition’ – their salute to fallen heroes Tupac and Biggie, and castigation of rap’s perceived death wish – doffed baseball cap to Boogie Down Productions; while the duo also rewrote Slick Rick’s ‘Children’s Story’. However, the album was also anchored by what was happening right then, hooking the pair up with kindred spirits like Common and Vinia Mojica. With wit and grace, it rejected the unthinking machismo and chauvinism that had latterly become rap’s rote. The standout was ‘Brown Skin Lady’, a rejection of misogyny and a celebration of Blackness that was as dulcet and irresistible as a Stevie ballad.

But even as the album seemed set to break the duo to a larger audience, an interview with MTV suggested they understood that the media landscape wouldn’t offer Mos Def and Talib Kweli an easy ride. “People always say we’re ‘progressive rap’ or ‘purist hip hop’,” Mos told the channel. “Okay, so what are the alternatives, like to ‘purist’: ‘watered down’?” “‘Progressive’, as opposed to ‘stagnant’ rapper,” added Kweli. “We’re rhyming about what’s sincere and real to us,” continued Mos. “We feel like we have a responsibility to be mindful of what we be saying.”

They weren’t standing in judgment of the gangsta paradigm – indeed, they were celebrating Tupac and Biggie – but neither were they going to play it themselves, like a charade. But there is a sense here that in not performing the P Diddy pantomime – the fantasies the white media machine expects young Black male artists to fantasise – Black Star will be perceived as suspect. I saw this in action myself in 1999, pitching a story on Mos to NME in advance of his solo album. “We don’t like ‘mummy’s boy rappers’,” the features editor snorted. The inference was, by not performing the role of dealer or street hood or gunman, Mos was a ‘mummy’s boy rapper’. Even though Smith had grown up in the same housing projects as Jay-Z, on the same streets as Biggie. The tone-deafness, the privilege and entitlement, to stand in judgement of his blackness from the ivory tower, left me speechless then and still enrages me now. It wouldn’t be the last time white media gatekeepers slammed doors in Mos’ face.

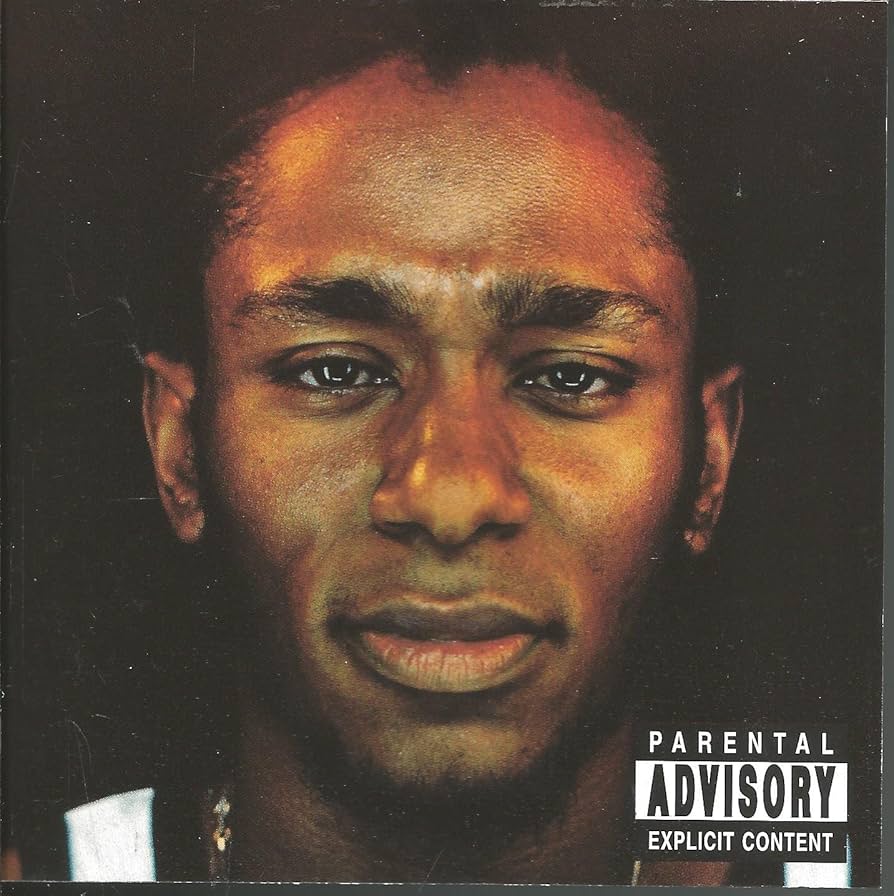

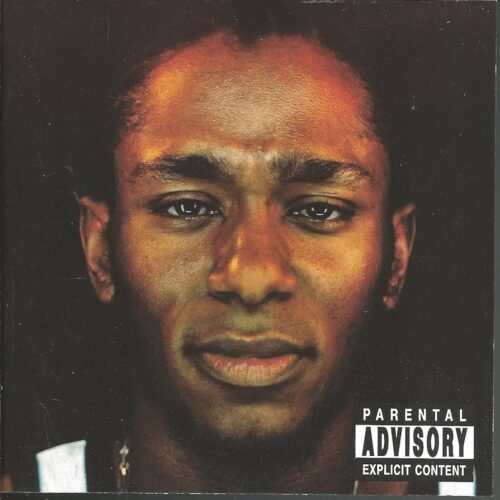

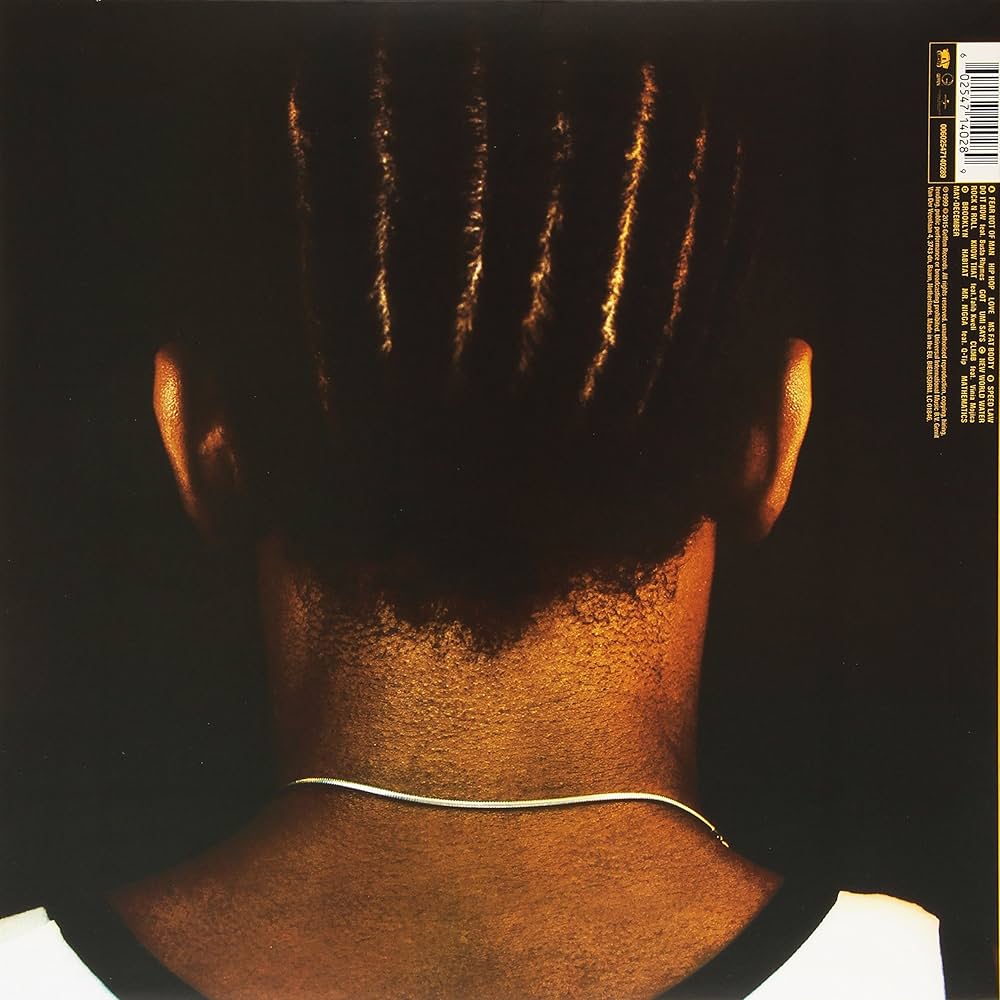

The title of Mos’s debut album, which arrived in October 1999, seemed to anticipate and pre-emptively reject this kind of insulting fuckery. Black On Both Sides was, by the standards of late-90s underground hip hop, an inarguably ‘big’ project. Just look at the talent involved: production from DJ Premier, Diamond D, A Tribe Called Quest’s Ali Shaheed Muhammad, The Beatnuts’ Psycho Les, 88 Keys and more; features from Busta Rhymes and Q-Tip, along with old friends Kweli and Mojica. In an era of bloated, big-name-heavy albums from major label artists, Black On Both Sides seemed a product designed to prove Rawkus could swing with the big boys.

But Mos is the star throughout, a fact intimated not through big-voice bragging but a beguiling, soft-throated intensity that draws the listener in. It’s a bolder project than ‘If You Can Huh’ might’ve had you predict, but that looseness and playfulness still pervades: ‘Fear Not Of Man’ opens the album with a conversational preamble, vamping on Fela Kuti’s ‘Fear Not For Man’, ruminating on hip hop itself, a theme that continues throughout the album. And this era of underground hip hop – the dawn of the backpacker rap phenom – was thick with hip hop about hip hop, and much of it was tedious. So it speaks to Mos’s skill and soul that he’s able to reinvigorate the subject, to reconnect the beats and rhymes to life.

Track two draws tight the amiable slackness of the opener; Mos is a man of many modes, and on ‘Hip Hop’ he’s at his most assertive. It’s a history lesson of sorts, opening with Mos reciting the lines to Spoonie G’s foundational 1979 anthem ‘Spoonin Rap’, then compressing several centuries’ progress into a handful of lines (“we went from picking cotton / to chain gang line chopping / to be bopping / to hip hopping / blues people got the blue chip stock option”), then balancing that with some ‘stakes is high’ wisdom (“You can either get paid or get shot / When your product in stock, the fair-weather friends flock / When your chart position drop, then the phone calls… [stop])”, then musing on hip hop’s role in laundering the once down-and-out Big Apple into a real estate bonanza (“luxury tenements choking the skyline”), then slyly tweaking the movement’s recent history (“hip hop went from selling crack to smoking it”) while, in the same breath, championing it as redemptive life-force (“medicine for loneliness”).

‘Love’ closes this opening hip hop-indebted trilogy, shuffling like the Daisy Age blurring into New Jack Swing and invoking Rakim’s deathless lines from ‘I Know You Got Soul’ from 12 years earlier (“I start to think and then I sink / into the paper, like I was ink”) to offer a more personal take on rap history. The focus now is on Mos’ own relationship with the artform, the narrative swinging from Mos’s own conception, to avidly listening to Rap Attack on the radio as a 10-year-old, to suggesting why Mos didn’t fall victim to a life of crime like some of his peers in the Roosevelt Projects, instead focusing on his nascent rhyme skills (“It was love for the thing that made me stay in the house”). The track is a paean to Mos’ love for hip hop, the energy he draws from that love and the feedback loop initiated by pouring that energy into making hip hop. The second verse is a deep rumination on the artform itself, both in spiritual and esoteric terms and the beauty of its raw nuts and bolts: “speech align with the rhythm / designed with the rhythm / ears and eyes keep in good time with the rhythm”.

Then the record drops the hip-hop-about-hip-hop angle (itself a method to speak about so much more) for the album’s Big Hit Single. ‘Ms Fat Booty’ was Mos’ mainstream breakthrough, musing on the complexity of attraction. Mos negotiates a relationship with a woman who initially shoots him down, who he later initiates a tryst with and who, nine months down the road, kicks him to the curb saying “commitment is something… she can’t manage”. The joy of the track comes from Mos’ insecurity throughout; that her power within the relationship doesn’t make her a villain within the song; the radiant pleasure of the long-delayed consummation (along with constant references to lovers rock and even a sliver of Gregory Isaacs’ ‘If I Don’t Have You’ in his trademark sing-song); and that final image of Mos rubbing his sore ego as she leaves him in the dust. It’s a subtle, complex masterpiece, which also doubles as a club banger.

And so Black On Both Sides rolls, its strut all killer and no filler. There’s ‘Umi Says’, a soul-jazz burner, Black Eyed Peas’ Will.I.Am on Fender Rhodes and Weldon Irvine on Hammond, tapping in again to that righteous Fela vibe inaugurated on ‘Fear Not Of Man’ and suggesting, with its infectious, revolutionary rumble, there’s nothing Mos can’t do. There’s ‘Do It Now’, all malfunctioning robot funk and note-perfect interplay between Mos and Busta Rhymes. There’s ‘Brooklyn’, an ambitious three-part tribute to his home borough long before it went bougie, its triptych of beats taking in Milt Jackson vibes, Roy Ayers’ atmospheric ‘We Live In Brooklyn, Baby’ and, in the final segment, Biggie’s ‘Who Shot Ya?’. There’s ‘Rock N Roll’, Mos expanding Chuck D’s “Elvis was a hero to most” line to song-length and reclaiming rock from the white guys in the name of Bo Diddley, Jimi, Fishbone and Bad Brains, before collapsing into a thrash-metal breakdown that takes no prisoners. There’s ‘Climb’, a dreamy duet with Vinia Mojica that plays poignantly with Diana’s ‘Mahogany’ melody, propelled by Dilla-esque drunk drums. There’s ‘Know That’, a powerful reunion with Kweli that “strikes the empire back”, centred on a loop from Dionne Warwick’s ‘Anyone Who Had A Heart’. There’s an imperial collab with Q-Tip on ‘Mr N*gga’, a sequel-in-spirit to Tribe’s own ‘Sucka N*gga’. And there’s the closing ‘May-December’, an instrumental with Mos on vibraphone and Irvine on piano that closes the album on a resonant note.

It’s a fierce, game-changing record, a savage display of talent from a young artist ready to take it all on. It’s aged extremely well, its blend of hip hop and neo-soul prescient, its lyrical and philosophical content of a piece with the modern-era thinking that the same clueless chodes who derided Mos then as a “mummy’s boy rapper” would now dismiss as “woke”. But Black On Both Sides is woke, as in alive, as in thoughtful, as in restless and ready to fuck shit up. Who wouldn’t have gambled on Mos Def as a star of the future, if not already the right now?

But it didn’t quite play out like that. A second album wouldn’t surface for another five years, during which time Mos juggled music and movies, and detoured with Black Jack Johnson, his heavy rock side-project furthering the mindset sketched out on ‘Rock N Roll’, and featuring members of Bad Brains, Living Colour and Funkadelic. Mos intended his second album to be a Black Jack Johnson album, but the gatekeepers spoke again and MCA Records, who picked up Mos from Rawkus, nixed that, wanting instead More Of The Same. Mos’ eventual sophomore full-length The New Danger was a curate’s egg, with fleeting and frustrating flourishes of the Black Jack Johnson material, some fine and hard-edged hip hop tracks, one visionary masterpiece track (the epic ‘Modern Marvel’, where Mos seemed to perpetually inhabit one bar of Marvin’s ‘What’s Goin’ On’ to ruminate on life and art and a musician’s responsibility and ability to change the world), but little of the pop-adjacent perfection that made Black On Both Sides such a phenom.

His subsequent moves were chaotic. He left MCA for sister-label Geffen, though his sole album there, 2006’s True Magic, was so half-hearted it didn’t even have a sleeve. His fourth LP, 2009’s The Ecstatic, was stronger, but it’s his last to his record shelves to date (a fifth album, ንጉሥ (pronounced Negus), exists, but Mos has no intention of releasing it, intending instead to have it played “at installations across the world”). He toured with Robert Glasper, changed his name to Yasiin Bey in 2011, started his own clothing label, UNDRCRWN, moved to South Africa and then ended up on the country’s ‘undesirable persons’ list, and announced his retirement from showbusiness in 2016. A new Blackstar album with Kweli, No Fear Of Time, produced by Madlib, dropped in 2022. It’s pretty good.

But it’s not where you might’ve expected Mos to end up, not the trajectory set by Black On Both Sides. The industry fucked with him, no question. He could possibly have done with a sage managerial presence to guide him through the minefield. He had seemingly limitless talent, and it burns that he’s been so stymied in his attempts this last quarter century to give that talent expression. Speaking to the LA Times in 2004, as The New Danger finally saw release, and having tasted the gatekeepers at his label slamming the door on his vision, telling him who they expected him to be, he seemed to anticipate how this game would play out: “The tragedy is with good artists who don’t believe in themselves and become disillusioned and disenchanted. That’s the real tragedy, when a guy starts with something that he really believes in, and then stops believing in his own taste or his own gut, that’s really sad.”

I finally interviewed Mos late in 1999, the success of ‘Ms Fat Booty’ proving to NME that it did like ‘mummy’s boy rappers’ when they sold hundreds of thousands more records than the mummy’s boy indie rockers who mostly populated the paper. He was smart, funny, charismatic and engaged, even as he fought jet-lag and the kind of exhaustion that kicks in when everything’s starting to happen and your feet seem to no longer connect with the ground.

He spoke most passionately about his reasons for making music – and, specifically, for making conscious music. And what he said makes sense in terms of how Black On Both Sides is music about ‘issues’, but also music about a human, and that in being music about a human and about how that human is affected by those issues, the record is infinitely more powerful than mere polemic.

“It’s the only thing that makes it all worthwhile, man,” he said, “the only thing that makes you feel like you’re actually doing something. It’s far more useful to do that than to just try and manipulate people to buy my record. You have to speak out against oppression; language is powerful, man. If I’m in a position where people listen to what I’m saying, I just wanna talk about more than just myself.

“I’m just one dude,” he added. “I can only be so interesting.”