While there will never be a consensus on the greatest horror film of all time, the award for the scariest has been sitting on the same femur strewn mantlepiece for fifty years. When it comes to pure cinematic terror The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has no equal. It doesn’t matter how many times you watch it, by the time Leatherface is twirling his sputtering chainsaw in front of the rising sun and poor Marilyn Burns is blood soaked and shrieking with maniacal laughter in the back of that pick-up, the viewer is a quaking, nerve-shot mess. I couldn’t tell you how many times I’ve watched it, but the result is always the same deep and abiding shock. You cannot just throw on another film after it and hope it goes away. It has the same impact on the viewer’s central nervous system that it had on cinemas when first released in 1974: scorched earth. It does not get more frightening than The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

The result of a weekend long filming excursion into the wilds of Texas with a minimal budget, conducted at a fever pitch by a stoner goofball with an EC Comics sensibility and a gross sense of humour, the trials suffered by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s tiny cast are the stuff of legend: a gruelling shoot that resulted in injury, mania, hurt feelings, odours that could awaken the dead and one of the highest grossing low-budget films of all time. One whose name is still shorthand for cinematic depravity decades later. Is it about Vietnam? Vegetarianism? The collapse of the American working class? The failure of the counterculture? That so much can be read into this cheap horror flick speaks to its power as a piece of art, but the reason for its longevity is simple: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is fucking terrifying, and its reputation will last for as long as there are movies.

It’s a shame that the same can’t be said for its director. Tobe Hooper, the shy and retiring Texan wreathed in a cloud of weed smoke behind the camera, has one of the most confusing careers in American motion pictures. Doomed to create in the shadow of his early, unrepeatable masterpiece, he never managed to capture the imagination of the public in the same way again. And is remembered – outside of horror fandom, at least – as something of a failure. A compromised, borderline lazy talent who never again scaled the heights of his greatest success.

How many of these films have you seen? Toolbox Murders, The Funhouse, Lifeforce, Djinn, Crocodile, Invaders From Mars, Mortuary, Spontaneous Combustion, The Mangler, Night Terrors, Eaten Alive. I’m guessing you’ll have heard of a few, but it’s odd that the director of the most hallowed fright flick of all time should have a back catalogue that’s gone borderline unexplored by all but the biggest genre heads. Tobe Hooper’s position as one of the faces on the Mount Rushmore of horror – alongside George Romero, Wes Craven, John Carpenter and David Cronenberg – is established mostly due to the effect of one movie, but an examination of his filmography reveals not a one-and-done chancer, but a director with a deep and compelling artistic vision. One that runs throughout his work whatever meagre budget he managed to scrape together.

(Let’s get this out of the way now: although its proper written title is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the agreed upon abbreviation is TCM. Whether this has contributed to the long held perception of horror fans as borderline illiterate, I don’t know, but that’s the one we’re going to be using.)

On paper TCM doesn’t read that differently to any of the slasher movies that ambled along in its wake: a bunch of kids in a wilderness one-by-one fall foul of a masked, weapon wielding psychopath. What sets it apart is its atmosphere. Whereas in the Friday The 13ths, Nightmare On Elm Streets and Halloweens that followed, the masked killer is an aberration, an unwelcome intrusion into the fabric of reality, in TCM reality is already on the edge of chaos and the killer is an outgrowth of a hopeless, poisoned world.

Over the opening credits garbled news reports breathlessly describe suicides, murders and grave desecrations, while images of disinterred corpses provide the inspiration for every extreme metal album cover for the next 50 years. The film’s extraordinary soundtrack, a kind of redneck musique concrète performed by the director himself, squeals and clangs like an abattoir door in a breeze. Death is everywhere, and it’s hot. Hooper captures the crushing heat of a Texas summer unflinchingly. This world feels like it’s winding down, like the celluloid itself is slowly melting, so by the time we meet Sally and her friends in the back of their camper van, we already know that nothing good is going to be happening to any of them. This land, the film tells us, is death.

And those kids! So resolutely normal. So completely undefined. Not the shopping list of high school cliches cemented in the slasher movies of the following decades – the jock, the nerd, the slut, the virgin – these are very average teenagers. They have few distinguishing characteristics apart from a liking for pot and some egregious bell bottoms. Even wheelchair bound Franklin’s constant whining serves more to heighten the tense atmosphere than to give him any personality. They could be anyone, and this lack of relatability is partly what gives TCM its kick. There’s nothing to gawp at or separate yourself from. They could be you.

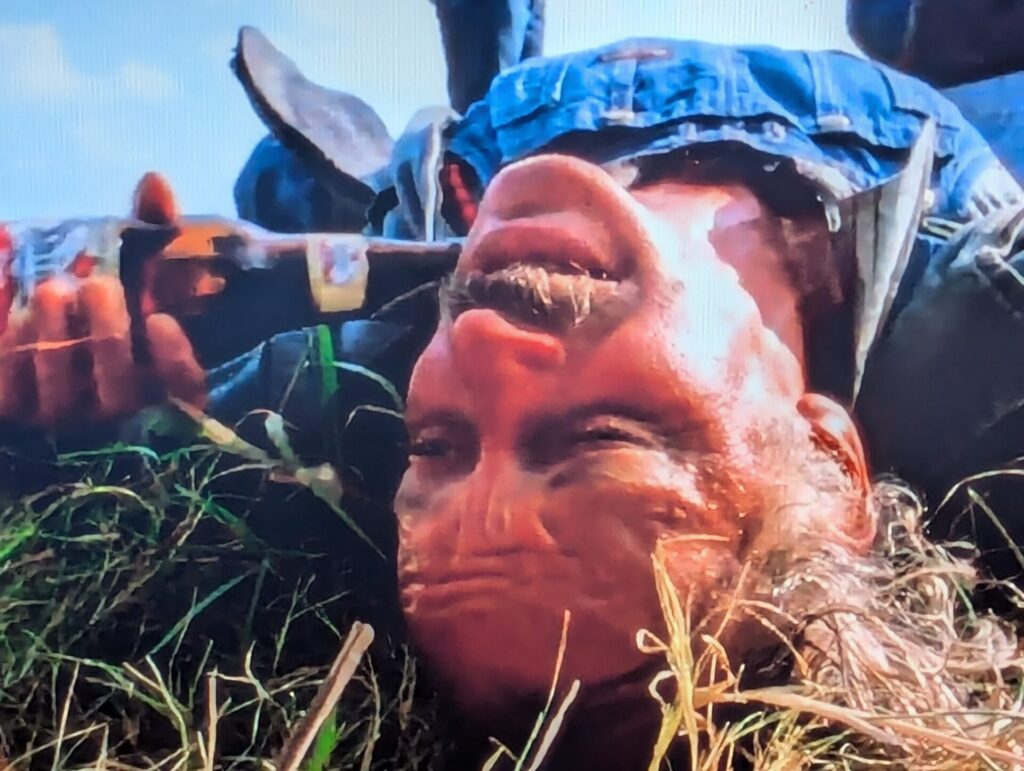

What follows is, by now, lore: the hitchhiker, the tight red shorts, the looming house, the hammer blows, death twitches, meat hooks, dismemberments, screams upon screams upon screams, and the relentless sound of the ever chugging chainsaw. Cinematic touchstones, endlessly parodied and imitated but their power undiluted. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is still a mean movie. Where madness is the only escape from death, and the land itself is locked in all-out war against those who trespass on it.

And its director thought it was a comedy.

One of the major factors that stands between Tobe Hooper and the kind of acclaim that he deserves is his sense of humour. Raised on the EC horror comics of the 1950s, their supernatural morality tales leavened by pitch black wit, and with a naturally cynical streak, Hooper always intended The Texas Chain Saw Massacre to be funnier than its audience thought it was. Edwin Neal’s performance as the hitchhiker is an early clue, feeling like it’s been beamed in from a silent comedy, all rolling eyes and exaggerated redneck ‘hyuck hyuck’ing. And Leatherface and family’s behaviour in the infamous climactic dinner scene is bordering on slapstick. But what Hooper found funniest was the sheer ‘too-muchness’ of it all. The incessant and escalating intensity that could only be broken by a hysterical laugh.

It was this unhinged sense of humour that Hooper chose to highlight in 1986, when his then paymasters Cannon films demanded a late sequel. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 was, for years, regarded as one of the worst follow-ups ever, a testament to runaway cocaine abuse and not much else, but it’s easy to see that, given a bigger budget and a bit more time, the original could have ended up being a lot closer to its belated sequel in tone and ambition. A lot of the intensity of TCM is due to the extreme circumstances and dire poverty of its creation. Everyone involved was somewhere else while they were making it, and it’s this channelled, mediumistic feel – like the film is drawing its strength from the run-down and desecrated country surrounding it – that Hooper found hardest – or was simply unwilling – to replicate.

There are flashes of this madness throughout his filmography – no director has ever been able to present unchecked hysteria with the same gleeful edge – but it was TCM’s follow up, 1976’s Eaten Alive, that was to provide the blueprint for most of the career to follow. Filmed entirely on shabby sets, the rundown motel owned by main protagonist Judd – proprietor, scythe wielder, keeper of hungry crocodiles – is a wretched creation in various shades of puke, populated by some of the largest performances in the history of horror. “Wither the stripped down, in your face naturalism of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre?” the fans and critics said, when confronted with this white trash Suspiria. “Where’s the reality?”

But is TCM really all that naturalistic a movie? With the exception of the kids the performances are all extremely stagey, it features a whole bunch of artfully constructed sets, and there’s no verité sloppiness to the gliding, confident camera work. Tobe Hooper was already a skilled filmmaker with a full length feature (1972’s Eggshells, a forgettably of-its-time hippy commune drama) and a host of commercial experience behind him, and he knew what he was doing. Who can blame him for not wanting to recreate the circumstances of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s traumatic birth on later films? Trying to put lightning in a bottle twice is just going to burn your fingers, and probably ensure that no one would ever want to work with you again.

It was this sense of heightened artificiality that Hooper leant into for most of his career, almost completely leaving the critics behind. Verité is a far more critic-friendly attribute than theatricality, after all. One gets the feeling that the things that Hooper liked about TCM weren’t necessarily what everyone else did, and it’s to his credit as an artist that his later films stuck to their guns. From the carnivalesque atmospherics of The Funhouse to the feverishly sexualised alien invasion narrative of Lifeforce, to The Mangler’s furious detonation of American industrial capitalism, Tobe Hooper said what he wanted to say, the way he wanted to say it, as far as any given budget would allow.

While this refusal to stay in his appointed box would forever mark Hooper as ‘difficult’, it was the mess that resulted from his involvement with Poltergeist in 1982 that would shape the reception to the rest of his career. Invited to direct by Steven Spielberg, then the world’s most acclaimed movie maker and at that point looking to make a break into film production that would result in the creation of Amblin Entertainment, varying accounts from the set as to the nature of Hooper’s involvement, or lack thereof, would tarnish his name for the rest of his life.

Googling ‘Who Directed Poltergeist’ unearths a slew of hypothesising YouTube videos, contradictory statements from actors and crew, and good old groundless theorising as to how much Hooper actually directed. Even an open letter to Hooper from Spielberg via the pages of Variety, hoping to put the issue to bed and thanking him for his “unique, creative relationship” has done nothing to stop rumours of his inaction behind the camera. But while Poltergeist has many elements of a film presented by Steven Spielberg – the Jerry Goldsmith score, the middle class suburban setting – and while it’s doubtless that Spielberg contributed more than most producers would have (who can blame him, given how much the film’s success or failure would decide the future of his career?) that Tobe Hooper is the director can be proved simply by watching the movie. If you think Steven Spielberg directed the entirety of Poltergeist then you’ve only seen one Tobe Hooper film, and I’d venture that you’re not that smart on Spielberg either. But dirt sticks, and so one of the most relentlessly creative and unique voices in American cinema is often remembered as a borderline fraud, and his early masterpiece as a sign pointing down a road that went nowhere. When he died in 2017 the Oscars didn’t even place him in the annual ‘In Memoriam’ section.

So, for the 50th anniversary of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre I’m going to suggest you do something unconventional. Don’t watch The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Instead watch Eaten Alive, Hooper’s maniacal tribute to the horror comics of his youth, that predates the style of George Romero and Stephen King’s Creepshow by half a decade, or the borderline psychedelic grime of The Mangler, or the balls-out lunacy of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, with its rabid Dennis Hopper performance, or Lifeforce, one of the most bizarrely imaginative and underrated films of the 1980s. Instead of again watching the most venerated horror film of all time and asking what might have been, make your way through the filmography of one of the most misunderstood directors in the genre’s history and celebrate what we have.