Unlike the Son of God, it took the acronymic Julian Cope three years to undergo resurrection. While on stage at London’s Hammersmith Palais in 1984, promoting debut solo album, World Shut Your Mouth, he lacerated his chest, stomach and back with a broken microphone stand. This was a bloody act which exacerbated a reputation for mortal folly already fuelled by the berserk mythology surrounding his former band, The Teardrop Explodes. In their final days, during an ill-starred recording session at Rockfield in September 1982, David Balfe locked bandmates Cope and Gary Dwyer out of the studio, leaving them to indulge in dangerous, intoxicated games involving speeding jeeps; and things reached a head when, Dwyer – allegedly, disputably – chased Balfe through the surrounding countryside with a loaded shotgun. There would be no third LP for The Teardrop Explodes. But after the literally performative self-harm, Cope’s appetite for psychedelic excess hadn’t visibly waned by the time he released Fried, his own second record. Released at the end of the same year as World Shut Your Mouth, its front cover featured a confused looking Cope prostrate atop a slag heap staring at a toy van, naked bar the giant turtle shell, which he apparently sometimes wore in the studio.

If this sounds like the nervous exhaustion of an acid casualty, it won’t be surprising to learn that in December Cope began an interview weeping in front of NME’s Jack Barron. Afterwards, he withdrew from touring and recording for eighteen months. “I was Mr. Paranoid”, he told Spin in 1987. “I never opened the door.” In the meantime, he was dropped by his label, Phonogram, after his debut merely grazed the charts – “that sad and weary thing,” NME concluded, “another rock album” – while Fried was even less successful. Afterwards, he confessed in the same interview, “My A&R man said, ‘These songs are shit, go away and write some more.”

Clearly, Cope wasn’t surrounded by Yes Men, and Yes Men are arguably a necessity when cultivating a budding God Complex. From Liam Gallagher’s “Every time I look in the mirror, God looks back” to Kanye West’s “God chose me”, such utterances are normally enabled by those around an artist trumpeting their brilliance, something the artist can easily take as a sign of infallibility rather than sycophancy. But Cope had Cally Callomon, who, after becoming manager and signing his charge to Island Records, encouraged a more responsible approach to verifying his immortality. Cope called time on the debauchery, and, among other things, took up speed-walking with weights around Tamworth, where he’d lived as a child and returned in 1982. “Such an uncool way of doing it,” he told The Guardian in 1986.

Even if he was less corruptible, by 1987 Cope still wasn’t “more popular than Jesus”. Sure, he’d enjoyed multiple, notoriously spangled Top Of The Pops appearances in 1981 with The Teardrop Explodes, performing Top 10 hit, ‘Reward’, not to mention chalking up two Top 30 albums with the band, but his career, at least commercially, seemed to be in decline. Indeed, to all intents and purposes – as former manager Bill Drummond had it in his response to Fried’s ‘Bill Drummond Said’ (from 1986 LP The Man) – Julian Cope was dead. His only hope for glory, the future KLF co-founder gloated, would literally mean him taking his own life, turning him into a martyr “with holes in his hands/ A halo round his head.” Fortunately, Cope had better – albeit comparable – ideas.

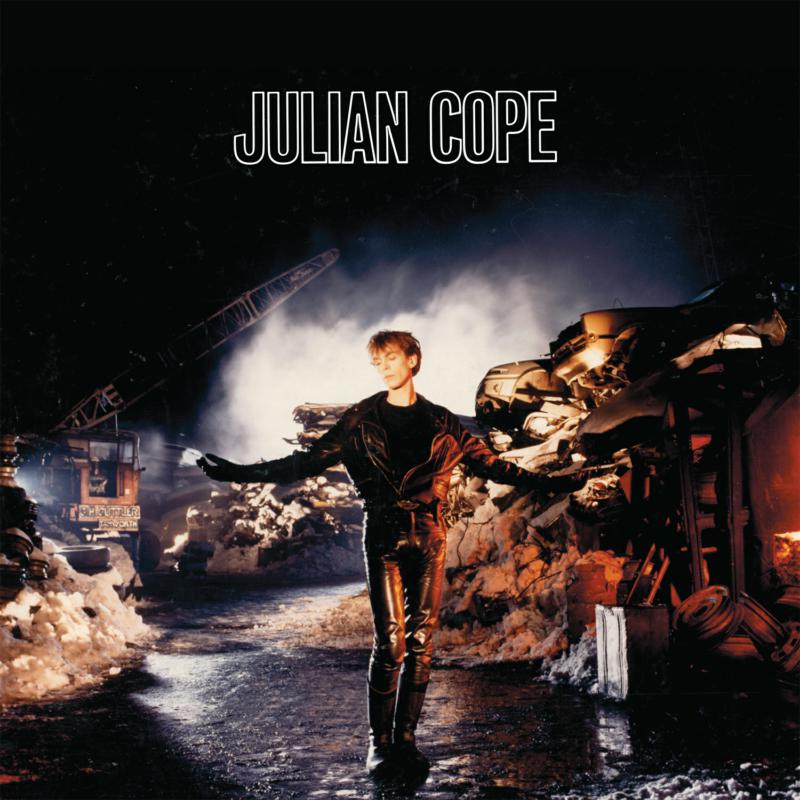

But Saint Julian strolled out of the tomb. The cover featured a trim-looking Cope stood in a junkyard at night, spotlit from behind, arms outstretched as though crucified, black gloved hands gesturing, as if to say, ‘Come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough’. In his wake lay a trail of melted snow, lined by rubble and wreckage. The location was revealed by a plaque illuminated on a battered crane indicating the Tamworth scrapyard in which the portrait was taken. (Its owner, Richard Cuttler – also bassist for Tamworth’s uncouthly named The Cheesy Helmets, who opened for Wolfsbane at the local Arts Centre that February – appears on the back cover, stoking the fires.) The message was bold, its intent was blunt: Cope was back from the dead.

Saint Julian had willed himself into being, donning sunglasses and leather trousers, matching Iggy Pop’s comical savagery with Jim Morrison’s absurd solemnity and early Alice Cooper’s vivid vaudeville, claiming crucial ingredients of musical folklore as his own. This was the sort of canonisation he understood: the subtitle of his celebrated 1981 compilation Fire Escape In The Sky was The Godlike Genius Of Scott Walker. But if he cast his mythical self as a new kind of Rock Saviour, there was a welcome grit to this incarnation, plus a self-awareness confirming Cope knew he was play-acting. It was as though he’d designed himself as a satirical antidote to Bono, who, in the wake of U2’s The Joshua Tree, was busy beating his bare chest in a leather waistcoast while pontificating about God’s country, locust winds, thorn bushes and the like.

The Irishman, in other words, had gone full method, starting to believe his own hyperbolic press during his crusade to bestride the globe like a colossus. In contrast, Cope The Idol wasn’t to be taken entirely seriously. After all, his new album’s title track began with lines delivered with the convivial astonishment of a man who’d run into an annoying neighbour while shopping at the Co-op: “I met God in a car in a dream in Ankerside/ And I was very unkind”. He’d also ordered a custom-made ten-foot microphone stand he named Yggdrasil – after the Old Norse for ‘Odin’s Horse’, also a word for ‘gallows’ – around which he could sprawl, lizard style, by his standards a curtailment of earlier messianic onstage indulgences.

Saint Julian was heralded by ‘World Shut Your Mouth’, his solo debut’s confrontational title rehabilitated as an anthemic stomper with Ramones producer Ed Stasium at the desk. The brilliance of this single justified the flippant designation he bestowed on his backing group, the Two-Car Garage Band. The similarly leather-clad group, featured Fried veterans Donald Ross Skinner on guitars and Chris Whitten on drums, alongside James Eller, who had played bass on Wilder, The Teardrop Explodes’ second album. ‘World Shut Your Mouth’ became Cope’s biggest UK single to date as well as his only US hit, while ‘Trampolene’ became another no-nonsense, successful 7″ to trail the album, stopping just short of the UK Top 10.

It’s true it wasn’t immaculate. Although Stasium was also responsible for the pummelling ‘Pulsar’ and carnal one-chord-wonder ‘Spacehopper,’ Cope later turned to producer Warne Livesey, who, fresh from The The’s Infected, occasionally over-egged the pudding with contemporary technical tropes across the seven tracks he helmed. The snare drums are, for instance, unmistakably of their era, and though ‘Eve’s Volcano (Covered In Sin)’ is appropriately theistic with a frivolous but self-aware chorus of “Doo doo doo doo doo”s – it tries too hard to please the crowd with its masturbatory revelry. In addition, there’s frankly no godly excuse for the Seinfeld-like slap bass solo on ‘Planet Ride’, however brief, nor drums machines better suited to That Petrol Emotion’s ‘Big Decision’, released around the same time. Even these slips, nonetheless, were redeemed by one of the most brillliantly unlikely declarations of commitment ever recorded: “I love you, sweedeedee, I love you/ Come and hang ‘em on the line next to mine.”

In the end, St Julian’s sheer scale, not to mention such reminders of Cope’s irreverence, overwhelm nitpicking niceties. ‘Shot Down’s vigorously grinding riffs and brooding, extended bridge offer a built-for-arenas vehicle for messianic revelations like, “On my cross I beg and cry a million mouths”, while the title track unites him with Kate St. John’s cor anglais for a largely joyful, succinct rejection of a one true God: “Then my flailing arms smashed your face”. Furthermore, ‘Screaming Secrets’, originally written for The Teardrop Explodes, was perfectly titled, its drums relentless, firing like machine guns towards a breathless climax, yet it was also home to wry, religious iconography which couldn’t help but raise an amused eyebrow: “I see you’re careless/ Even you were circumcised”.

It’s the epic finale, ‘A Crack In The Clouds’, that lifts Saint Julian to its most sublime peak. Opening with more plaintive cor anglais, as if recorded in a decrepit, rainswept church, its noble swagger is built upon a simple acoustic guitar riff, with Cope touting apocalyptic imagery: “I stand and sigh, weighed down with chains/ They follow me in columns”. That’s until the chorus which explodes with a redemptive emancipation further heightened by its ultimate, major key reprise and a grand orchestral outro. God was now in his heaven. All was right with the world.

Admittedly our hero would reemerge a year later with My Nation Underground, a more clumsily earthbound, chart-minded collection (also available once more on vinyl), considerably less sure of his newfound identity as a pop star. But on Saint Julian he elevates himself in his own, unique image; an act of self-anointing deification still as thrillingly convincing as it’s ludicrously entertaining. Whosoever believeth in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life. As for those who lack such faith, put your head back in the clouds and shut your mouth.