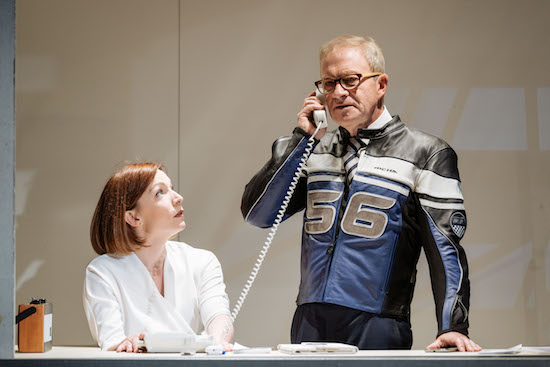

Kirsty Besterman and Harry Enfield in Genesis Inc. at Hampstead Theatre. Photo by Manuel Harlan

Dear Friend

I apologize for the slight delay in replying to your kind and respectful letter: I have been plagued by a malaise during this long hot summer, and the distractions of international sport, but feel recovery is imminent. First let me offer you my congratulations at your recent success; how glad I was to hear that your play is up and running on a main stage in a prominent theatre. I know how hard you have worked towards this end. But your letter also indicates your disquiet – nay, at times, your turmoil – at the conflicting feelings in your heart. You wish to know how best to survive this intensely public reckoning; how to navigate the choppy waters of critical reception; in short, how to survive it with dignity and grace. Now, since you have allowed me to advise you, I have some suggestions that will, I hope, provide some respite.

But let me start by addressing the foremost question burning at your brow. You ask me whether your play is any good. You ask me, you have asked others before. You compare it with other plays and you are dismayed when certain critics reject your efforts. I beg you to put all of this from your mind for the time being. Fear not, I am not one of these new-fangled modern relativists who feel that no individual assessment of a work is meaningful. Nor am I a gatekeeper of some long-established and outdated cultural value system. I am, above all, practical, as all playwrights must be if they are to survive. My first piece of advice is this: do not read any of your public critiques, good or bad, during the run. Your adrenalin, fear and hope, along with the intense collective efforts required to get the show up on its feet is exhaustion enough. Do not run the risk of being tipped into despair or hysterical elation. Wait a month or so and then read the ‘good’ critics – that is, those people that you trust to give an intelligent, considered response, whether or not they like your cherished play.

A word on them, the estimable theatre critics – paid or unpaid, broadsheet-validated or voluntary essayist. They are the people whose experience and intellect and enthusiasm for theatre can enhance the audience’s experience as well as your own understanding of your work. You will know them by their passion, which has not become soured by disappointment; their equal consideration of the play for children or the black-box studio show as the West End revival offering gourmet interval snacks. Their role, as one such estimable critic has said, is more midwife than gatekeeper; their intent is not to rip the newborn play from the birth canal and loudly drown it in a basin, but to briskly slap its dimpled arse and encourage it to breathe and grow. So remember that in these times of frothing public rage, we more than ever need the thoughtful opinions of clever, experienced, passionate lovers of culture, who want to reflect on art, enhance audience experience and encourage civilized debate.

As for the inestimable ones – those self-styled provocateurs who tend towards bigotry masquerading as satire – pay them no attention. They are as Mr Statler and Mr Waldorf, those elderly Muppets heckling from their plush theatre box; more invested in their own wit and vitriol than the merits of demerits of the work. Do not be misled, for they do not always resemble old men with unpruned nostrils – there are Statlers and Waldorfs with bosoms and state educations. You will know them by their tone, redolent of bleak boarding school dormitories in which small boys learned that sardonic cruelty was the fastest way to avoid further beatings. They will reveal themselves in their frequent lament of taxpayer’s money badly spent on tasteless subject matters or experimental form, and their love of plays that feature some kind of military conflict, even more so if they can approve the authenticity of any featured firearms. But they do possess one powerful weapon of their own, which can wreck writers’ lives, and that is shame. Shame is the deadliest force for any creative artist, and you must learn to turn your cheek, dear writer. Never feel embarrassed by your attempts to create something meaningful and put it out into the world. To do so would be to let the Statler Waldorfs win, and this cannot be permitted.

Of more importance now is your understanding that the reckonings of either tribe cannot answer your question about your play’s worth, dear writer. There are only two true judges of its value. The first is yourself. We writers are necessarily always our own harshest critics, but remember that we operate in a creative bubble – at first while writing the play and then when crafting the production in rehearsal. As soon as the play is up before a live audience, our snowblindness instantly melts, and only then do we truly understand what we have made, and whether or not it works. This is where the second judge becomes of great import – the audience. You must learn to listen to her, to watch her, to absorb her energy, for she will tell you what you have achieved and where you have failed. You will quickly learn that she is far cleverer, more instinctual and perceptive then you might have imagined. Like a pre-verbal infant with good hand to mouth coordination, she will quickly show you when she is stimulated and just as equally when she is bored. She, your expectant witness, is the being who will give your work its true life, and she will change every single night, depending on her collective whim; mood, hunger, a satisfactory bowel movement. All of this is beyond your control, and in this letting go lies both the thrill and the terror of making live theatre.

The cast of Genesis Inc. at Hampstead Theatre. Photo by Manuel Harlan

A note of caution, next; if your play is based on your own lived experience, then a harsh critique from audience or reviewer can sting sharper than it might do otherwise. You must trust that these responses are not intended as a personal comment on your life (excluding those of the Statler Waldorfs whose aim is often just the opposite.) Your art is merely being taken on its face value – that is the critic’s job, so respect it and do not succumb to fear and resentment. Remember too that is highly likely that nothing can be said about the work that is worse then the experience it was based on, e.g. spending many an hour with one’s legs in stirrups having one’s ovarian follicles graded like a defective drama. Likewise, remind yourself that to aim for ambition in form and subject matter takes courage, although the risk is that your play may fail harder and further. But so be it. Be strong, my friend. The only benefit of not writing the play you so desire, is that you avoid becoming a fly ensared on the stickiest of theatrical Möbius strips, one side of which laments the lack of ‘ambitious new writing’, especially by women, and the other which damns ambitious new writing, especially by women.

Equally, do not expect or ask to be rewarded just for your hard work, dear writer. Only you and your creative team will ever know how much sweat, blood and tears were shed in its development, how many Hobnobs eaten, how many brilliant speeches excised from the script, and that is as it should be. Remember that it is, if I may be frank, hard enough to write a mediocre play, let alone a fucking good one (please forgive my lapse into crude linguistics) – in the interests of quality control you cannot allow yourself to be blown off course by the noise that surrounds your play. It is an imperfect product, of course, but it is now alive. Is this not miracle enough, after the months and years it has been confined to paper, to bear you along on a river of hope towards your next production? Your play was precious to you as a manuscript, yes, but would you rather it stayed trapped in its perfection on the page, or given the chance to live? You will either try and die trying, or you will not bother at all. And all art, my sensitive friend, stems from being bovvered.

Oliver Alvin-Wilson and Ritu Arya in Genesis Inc. at Hampstead Theatre. Photo by Manuel Harlan

A word next on the great public forum, nay, the slithering snakepit which is now called Social Media. Do not go looking there for praise or damnation, for you will find both in overwhelming numbers, along with Partisan views or clever quibblings in which today one view wins and tomorrow the opposite. It is not all bad, however. There are many humans working hard to drag our beloved art form into the bright pixelated glare of this still new century. Their cry is for diversity in experience and expression; for calling out bigotry and elitism; and for challenging the dominant narrative of the London-centric, white, male, middle class perspective that has reigned for so long in every aspect of theatre craft. (Fear not if many of your best friends are white, male and middle class. I predict they will come back into fashion before the end of this century.) Many of these cultural dissemblers are excellent writers, and most of them are doing it without payment, and that takes grit and dedication. If at times some of them appear to have taken on the mantle of the Statler Waldorfs in their damning tone, trust and hope that their rage will settle. They may learn in time that anger about the historical failings of a privileged elite can and should lead to cultural activism. But that didactic arrogance does not make for good cultural criticism, even if the writer’s politics are liberal and inclusive.

Oh, my dear friend, let me pull back a moment, for I feel the exhaustion settling ever heavier on your shoulders. I understand your weighty sorrow. I too know that it may seem as though the entire critical arena around our beloved theatre has become a depressing industry echo chamber: the essays and reviews on all sides read and discussed in the main by theatre professionals, deepening the existing tribal divides and preventing any real or honest dialogue between practitioners and their critics.

The heaviest burden is that we are all of us having to pretend. Playwrights must pretend not to care about our critiques. Theatres to pretend that it doesn’t hurt ticket sales. Paid critics to pretend not to fear being usurped by younger writers desiring to be modern cultural gatekeepers. But ask yourself, dear colleague, what exactly is behind the oh-so-carefully guarded gate? An empty field full of cowpats dropped from the bowels of Statler Waldorfs bloated on self-importance and acrid Press Night wine? A group of young bloggers poking the rotting corpse of traditionalist theatre with a stick whittled from the femur of Kenneth Tynan? The non-existent perfect play?

I will tell you in confidence who is not behind the gate – and that is audiences. They wandered away from the field years ago and found their own seats in the theatres all by themselves. Because ultimately, they simply want a good night out. And that is down to you, my friend. You must focus on the work, the work, always the work. Creating art is a work of infinite loneliness; so be glad that after your hours of solitude, you were given the chance to crawl out of your work cave and frolic with your company among the paradisiacal bean bags and chipped mugs of the rehearsal room.

The cast of Genesis Inc. at Hampstead Theatre. Photo by Manuel Harlan

Let me end with a reminder that the theatre is the most paradoxical and complex of the dramatic arts. It is a popular art form (if one can afford the tickets) with a tradition of academic discourse; a self-professed art of the ‘now’ and a commercial industry dominated by revivals of old plays; it is both literary tradition and performance art. Its old guard protects the old and fears change, and its inheritors have hard-won political agendas. No wonder then, that any playwright dipping her tender toes into its waters might find sharp objects underfoot that make her squeal. But dip she must, if she is to wade into the water and feel its delicious coolness; or else forever watch from the shore of cowardice, safe in her ignorance about what it is to be a real writer.

And now a final word of advice, dear fellow artist and kindred spirit. Be kind. To yourself, to other writers, to your detractors as well as your admirers. Respect those with integrity, and avoid engaging with those who do not. Remind yourself that playwriting and playmaking are acts of love, commitment and dedication, on all sides. When in doubt, look inward. Reconnect with your passion. Search for the reason that bids you write; find out whether it is spreading out its roots in the deepest places of your heart, acknowledge to yourself whether you would have to die if it were denied you to write. And if this should be affirmative, then build your life according to this necessity.

And finally, to answer your outstanding anxious question, ‘what is a dramaturg’? My answer is, do not concern yourself with this. It doesn’t matter that you do not know, for nobody else knows either.

All success upon your ways!

JK

Jemma Kennedy’s play Genesis Inc. runs at the Hampstead Theatre until 28 July