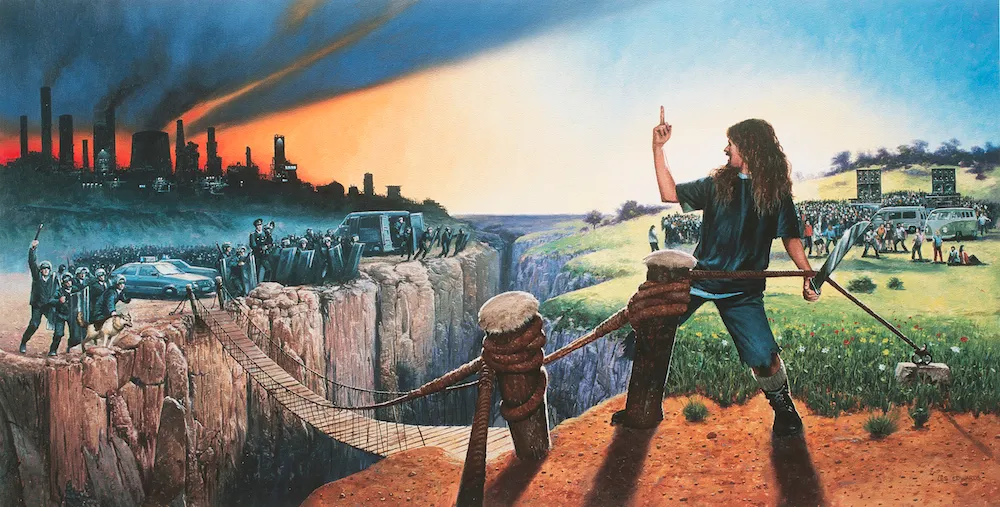

Recently XL reissued Experience: Expanded, the sounds of the bracing first flush of rave, along with More Music For The Jilted Generation, one of electronic dance music’s high water mark releases. Finally, enough time has passed to judge these albums separately from the metal-lite, stadium direction that The Prodigy took (for an admittedly shortish period of time) with Fat Of The Land. The debut sounds as if someone has stuck a DAT recorder straight into the bewildering energy rush coming out of generator powered sound systems all over the South East and taken a psychic field recording of what was happening in the early 1990s. The naysayers stopped listening after ‘Charly’ because of its novelty overtones and the legion of ‘toy town rave’ imitators that came straight afterwards. More fool them. Not only did they miss out on a TUNE but also on the disorientating rave distillation of ‘Out Of Space’ and ‘Jericho’ but they were soon having to eat their words after the release of the sophomore album. Put simply, The Prodigy were one of the few bands/crews to be good enough to make the transition from rave’s frenetic and anarchic birth to becoming a big name during its imperial period with tracks such as ‘Poison’ and ‘Voodoo People’.

Just after the reissue of their first two albums and on the eve of their Invaders Tour, we speak to Liam Howlett, Keith Flint and Maxim Reality, who are in good spirits – albeit hung over.

The last few things we’ve heard from you have been a greatest hits and two reissues. It was well documented that you were going through some rough times before then but would it be fair to say that the last album (Always Outnumbered Never Outgunned) shifted something of a creative blockage?

All: Oh yeah.

Keith: It was necessary and for me it was the best album. It did what it did to get us back on the road. It made us hungry and it woke us up in some respects.

Maxim: And it wasn’t what people were expecting. It wasn’t Fat Of The Land part two.

Liam Howlett: We really downplayed it. It was designed to put us back on the map with a good feel you know. We’d been away for such a long time. For us it was about regaining people’s respect and getting back to playing live again. You need to play live to survive.

I think it’s one of the most consistent pieces of work that you’ve done. You (Keith Flint) say that it’s your favourite album. I’d say it’s mine after Music For The Jilted Generation. Given this, aren’t you annoyed that it didn’t do better?

Liam: No. It all keeps you hungry and we’re still here. Whatever happens happens. That’s down to the audience it’s not down to us. But none of it affects us. If we had’ve sold three million albums off the back of it we wouldn’t have changed anything that we’re doing now. We still would have done all the touring.

Keith: We still would have done all the touring that we did. We still would have gone on stage at festivals at the same time. It doesn’t really affect that much. It didn’t affect the band. There wasn’t a group meeting where we went: “Right. What are we going to do now?” We did what we needed to do anyway which was get the band back on the road and touring anyway and to get the energy – the energy – of The Prodigy back.

Maxim: The pressure from the big expectations has kind of given us the freedom to do what we want to do.

It’s interesting that this album has the most diverse range of influences but it is more recognisably dance based. There is electro, synth pop, rave – you can hear the influence of bands like The Beastie Boys. And Liam, you certainly decided to try and educate people about how diverse your musical tastes were through your Dirtchamber Vol 1 mix album. So given all this and the reissue of the first two albums this would be a good point to ask what first inspired you to make music and get behind the decks yourselves.

Liam: Right in the beginning? The first record I heard that made me think that I could make a record myself was Grandmaster Flash’s ‘Adventures On The Wheels Of Steel’. He was cutting up Blondie and Queen. I knew there was some hope for me to have a record out one day because I knew it was such a punk rock record to release; to be able to do it yourself. Plus I was into the hip hop culture. I wasn’t really bothered about record deals I just wanted to be making records that I liked and to be in a gang. To be a DJ was my way into that. And once I’d learned the DJ stuff with my band Cut2Kill [Essex based hip hop crew[ that’s what got me started. The technology developed and then one day I was in a music shop and I saw this keyboard which was a Roland W30 which had a built in sampler and sequencer built in. It was the future. It meant you could write entire songs on it. I saved up and bought it. It was a grand which was a lot of money.

Keith: He saved up from his paper round!

Liam: That’s right! Seriously – I only earned eight grand a year. It took me ages. So then I locked myself away for about four months learning how to use this new keyboard. And that’s when The Prodigy really started around that and going to raves for the first time in 1989 and 1990. I’d come back from parties really inspired to write music and make records.

Ok, now don’t take this the wrong way because if I’m accusing you lot of being old cunts then I’m saying the same thing about myself because we’re all the same age, but I always kind of hate it when people used to go on to me all misty eyed about punk because I was far too young to have experienced it first hand. By the same token do you think that people of our generation are far too misty eyed about rave in the 1987 to 1992 period? What was it like for you? Was it a revolutionary experience?

Keith: Funnily enough we were talking about this just the other day.

Maxim: People talk about it with so much love and passion. It was a proper scene when it started. People get confused because they think it was all glowsticks and shit like that. It wasn’t like that. It was really hardcore with East London pirate radio, East London warehouse parties.

Keith: It was dirty, it was lawless. It wasn’t known about. People had no idea about where they were going to be going at the weekend. But in the same way, we’re determined not to be snobs about it. “Oh, you weren’t there back in the day, you’ll never understand.” You know what I mean? That’s bollocks. I’m sure there are people going out to grime/dubstep things this weekend. It’s their first time out and they’re only 17, they’ll be in some moody club and doing drugs for the first time. Fucking hell! That will be mega! It must be. But as you mature with it (rave scene) you start to realise that was a movement. That was a proper scene.

Maxim: It was a movement that drew a boundary line between youths and adults.

Keith: It was British. It wasn’t American. It wasn’t sponsored by Burger King. And that’s mega. If you’re down your local skate park – as much as I’m not wishing to knock it – you are kind of wishing that you were in LA or somewhere when you’re actually down Harlow recreation centre.

Liam: It’s true! When I was a teenager I would be down Essex Trainyards wishing I was in the Bronx.

Keith: It’s true. This was real. I remember driving down a big proper mansion road by some industrial estate and the cars were parked from garden to garden blocking the road. Everyone had come out and rammed this warehouse. There were police with dogs there you had to dive to get into this place and the soundsystem was fired up. And there were old men in their pyjamas going ‘Oi! You can’t park there!’ and this one geezer went: ‘It’s alright. We’ll be gone by morning.’ That is lawless and we were involved.

Maxim: The good thing about that scene was there were so many cultures involved in it. It was the same as the ska scene in the late 1970s with the punks and the rastas.

When you were working on early tracks like ‘Charly’ which is on the reissue of The Prodigy Experience, what were your actual ambitions? What did you think you were going to achieve?

Liam: Our only ambition at the start was – you’ve got to remember how early this was – to go out raving.

Keith: I used to plague Liam because he used to play the best records. I used to go up to him going ‘Ah geez! Play that fucking record!’ I mean, I wasn’t a dick or anything. [Liam and Maxim start laughing] I’d go on to the after party and I’d be mangled off my head saying ‘Ah mate, play that one that goes whoop! whoop! whhhahey!’ And he’d say yes. I just really digged what he was doing because he had the beats and the buzz. That’s how we met. So one day I was walking down the road – twatted – and he pulled over in his car and handed me a tape and said it was a mix on one side and his own tunes on the other. Thank God I didn’t lose it. On one side there were all my favourite tunes and then I turned it over and – Christ! It was amazing. I was just wondering why he wasn’t playing stuff like that! So I took the tape to Leroy [Thornhill – member of The Prodigy during the first three albums] and said let’s start a PA. And we went up to Liam and said ‘Look mate, we don’t want to be blagging off you or anything like that but do you want to start something. And that was it.

Maxim: We were four geezers who were really tuned into what we wanted to do.

Keith: Really we understood the ethic behind it. To have the loudest beats, the best bass lines and the biggest sounds.

‘Charly’ still sounds great now if you ask me but do you feel any responsibility for any of those terrible tunes that came out in the following months, like the Sesame Street one or the Trumpton one?

Liam: All I can say about that is I met the guy who did the Sesame Street one once and he came up to me at the Astoria and he told me that he thought it was a laugh and that he’d earned a bit of money off it. And I told him he was a bit of a twat and walked off. I dissed him because I thought ‘God. Has it come to this?’ I did ‘Charly’ for me and my mates. It was supposed to have a bit of humour in it but it wasn’t meant to be a novelty record. It’s got a wicked tune.

Maxim: You can’t be responsible for what everyone else does. Every piece of shit on the bandwagon. It was a bit weird around then and only a few people survived outside of the rave scene. There was us, Orbital and not many others. Natural selection.

Maxim, how did you first become aware of The Prodigy?

Maxim: When I was on stage with them!

Keith: I lived in the same town as Maxim and he’d decided it would be good if he managed us! This was before we had a record deal. He knew a few promoters, he knew the scene, he could talk the talk.

Liam: I was like, well there’s three of us, we could do with someone to run things. Keith said he knew someone who was involved in the reggae scene. We were supposed to be meet him at a record shop and he didn’t turn up.

Keith: But then he just turned up an hour before the gig and said ‘Right, I’m ready to go.’ He went on stage with us and pissed it.

Maxim: It was just a matter of getting on the stage. I didn’t have a clue what I was going to do. I was just going to freestyle some lyrics like I would have done at a reggae gig. I didn’t have a firm idea what I was supposed to be doing.

Keith: That was alright because we didn’t have a clue what we were doing! We’d never done a gig before. New band. Wet behind the ears. Didn’t know how to set the gear up. We got to the venue, The Four Aces in Dalston [Hackney, London] at midday. We weren’t on until 2am. We talked to the owner who asked us what sort of band we were and we said we wanted to be like one of the greats like The Pistols or The Clash or Pink Floyd. He said that they didn’t usually have bands on. They’d had a band on once but they got dragged off stage and beaten up. We said ‘That’s nice. We’re really looking forward to our first gig.’ That was the Friday night and straight away afterwards he asked us back to do the Saturday night. And that week we were offered two months worth of work and we never really stopped touring for eight years.

Off the first two albums which are the singles that you are most proud of and why?

Keith: I think ‘Poison’ is definitely one.

Liam: Yeah, I’d say ‘Poison’. It came out at the time when everyone was getting into fast beats. Things were getting faster and faster and we were flipping it back and dropping it right back down to a hip hop tempo. It still had the heaviness and the toughness though. It had a great video as well. Everything was right about that track. It wasn’t a massive hit but it was . . . proper. We realised a lot of things about ourselves around that time.

Experience: Expanded and More Music For The Jilted Generation are out now on XL.