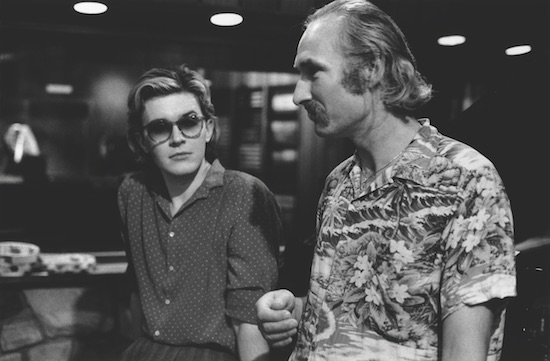

Holger Czukay and I were in constant contact during the 80s so to receive a request from him asking me to come to Köln when convenient wasn’t unusual. Specifically, I’d been asked by Holger to supply a vocal for ‘Music In The Air’, the final track on Rome Remains Rome, which was released in 1987. This places us back in the Winter of 1986. The night I arrived in Köln and drove on out to Can’s studio, Holger was in high spirits.

I’d arrived on a winter’s evening. I probably checked in the little, suitably depressing, pension a short walk from the studio and then we convened at Holger’s favorite restaurant where, as was custom at the time, I watched him consume a plateful of cooked meats while I picked at some bread, the only vegetarian option. We drank some wine, spoke of tomorrow’s recording, and then made our way to the studio. This was likely the first time I’d visited Can’s recording home, the ramshackle, but oddly beautiful abandoned and reconditioned cinema. The walls were lined, floor to ceiling, with mattresses. There was no separation between studio and control room, there was just a large open space in which to work. The words ‘studio’ and ‘control room’ sound entirely inappropriate as I note them here. No such conventions existed. (Holger, giggling at the absurdity of his earlier set up, frequently told the story of how the first console he’d purchased simply had two settings ‘Loud’ and ‘Soft’).

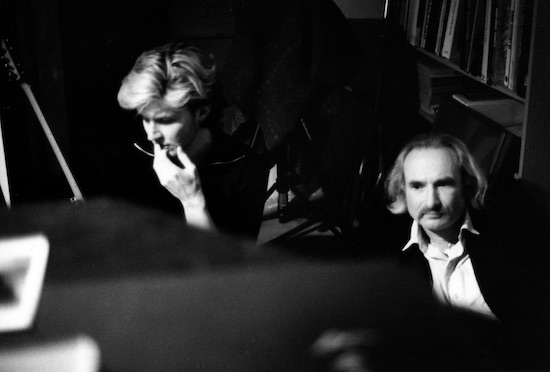

I started to wander around the room. Along the left and right sides of the room, a variety of instruments were lined up. Towards the back was a grand piano and behind that, at the very back of the room, Jaki’s set up. I’d always loved the sound of pump organs but had never had the opportunity to play one. I quietly seated myself and started up a drone of sorts, letting the bellows breathe, an asthmatic wheezing of tones which appealed to my ear. After a short while I heard various orchestral samples being pumped through a fold back system I hadn’t taken stock of, dotted around the open central space of the studio. I fell into a trance as I played along with the ethereal sounds which looped over and over, resounding around the room. After a while I got up and moved to the piano. I dabbled, looking for a pattern to complement the loops, I played for 10 to 15 minutes or so before I found what I was looking for when Holger announced ‘That’s enough David, move onto something else’. It was then I realised that the analogue multitrack was in record. Until that moment I’d no idea this impromptu performance being documented (Holger would often boast that he’d frequently record musicians while they were least aware of it. I thought this highly unlikely considering the self regarding vanity of most of our kind). Holger had cut me short the moment he’d heard me begin to ‘compose’ a line. He’d only wanted the process, the uncertainty, the ambiguity of the searching out of ideas. And so the night went on.

I’d pick up an instrument and play until a figure began to emerge and then the machines would be taken out of record mode. The result gave the unanticipated impression there was no one person dictating the direction of the piece, as if the sounds on tape were created by the ghosts of the instruments themselves.

The initial mood was perhaps dictated by the first drone I’d played on the pump organ, but that in turn was influenced by the large space of the room itself, the supposed end of an evening, the bare winter trees (which still now rise up with clarity in my mind) glimpsed on the drive out of Köln and into the country backed by the evocatively barren German landscape as memorably depicted by the painter/sculptor, Anselm Kiefer. The layered earth, patches of dirtied snow, trickles of water, the dried, dusty remains of autumn. Oh and the cold, the biting cold which the heaters in the room valiantly tried to abate. What I’d taken for the end of an evening was far from over and we emerged from the unlit cinema’s exterior as the sun was threatening to rise.

The pension room was cold. I was hungry. I slept as best I could. By the time I woke it must’ve been late the following day. I remember little of what happened before I reached the studio. The smell of burning coal in the air as I took the short walk from A to B. I longed for a coffee and a bite to eat. I found a tiny general store and bought some pumpernickel bread and butter. Holger had some coffee brewing in the studio. We listened back to the previous evening’s recording and felt we’d touched upon something. While we were absent a form of music seemed to have been created by instruments abandoned to the earth and the woods, sounded by the coarse winter elements. This impression motivated us to continue to pursue the same line of inquiry for another evening. Events unfolded very much along the lines of the previous night. Holger’s beautifully manipulated loops created the backdrop to which I’d respond, removing all traces of myself from the ‘performance’ (such an inappropriate term) as humanly possible. I bowed out once the playing became too aware of itself, too knowing.

Next morning I was due to head back to London, the vocal recording for ‘Rome Remains Rome’ entirely forgotten about. We’d stumbled across something far more powerful and rewarding.

This wasn’t my first excursion into improvisation. I think I’d trace that back to a piece entitled ‘Steel Cathedrals’ but working with Holger hadn’t simply ratcheted up the degree of improvisatory content, I’d arrived at a new plateau in my personal musical evolution, a point from which they’d be no turning back. Although Holger wasn’t by any means out of his comfort zone, this recording marked him in a way only he could expand upon. On many pieces that were to appear in his later work you hear him attempting to recreate or further this, let’s call it absence and evocation, over and over again, even reusing some of the samples framed in the original context of Plight & Premonition.

It was to be some time before we got together again to mix the work. In the meantime Holger had made some breakthroughs with ‘Plight’. I imagine ‘Plight’ emerging from the second night of the two sessions. It didn’t stand up as a finished work at the time of my departure. Holger had added some more samples, a minor piano motif, a flute sample, etc., accompanied by some very radical, audible, editing. I thought this very brave. I remember I once played Holger’s ‘Movies’ to an engineer I was working with. He kept laughing, part admiringly, part mockingly, at the seeming technical ‘errors’ in the work. But this was one aspect of Holger’s approach that helped him find and explore his own, I dislike the term idiosyncratic, unique means of utilizing technology for his own innovative ends. His approach to recording, editing, and mixing were unorthodox, apparently self-taught, and adjusted/evolved over time to create a method of working that was unique to himself, the results of which exhibited and confirmed this.

His approach was obviously linked to his almost playful, intuitive, editing of tape, be it two or multitrack. He frequently referenced Stockhausen for whom he had enormous respect (even taking me on a ‘map of the stars’ guide through Stockhausen’s neighborhood) focusing particularly on ‘Hymnen’, which he claimed was the first use of shortwave radio in composition. If one was to applaud his own innovations in sampling (as he was surely the first artist to employ this methodology in the context of popular music, anticipating a technology yet to be utilized and exploited by all manner of machines in the years to come), he would defer to this one composition by Karlheinz, a personal mantra and mentor. But his methods were truly his own. His editing of ‘Plight’ appeared to have more in common with film editing than music. It was as if he was splicing between one scene and the next or from the same scene only from a slightly different angle or perspective. I’d never heard anything like it, never seen anyone approach editing in this manner before.

To this we can add his use of dictaphone. He’d brought two large machines with him to the Berlin sessions for ‘Brilliant Trees’. He’d discovered these antiquated machines dumped outside of an office building in the city. He’d recognized their potential and, back at the studio, started to explore the possibilities they presented. As he later said during our first meeting, “I’ve so much more flexibility with these machines than any sampler on the market” and, in general, this was most certainly the case. He could improvise with samples, running the playback head of the dictaphone over a broad expanse of tape which he’d prepared with all manner of samples and sounds, many taken from his own studio environment, incorporating the use of the varispeed function which, as far as I’m aware, was the only other that the dictaphones had. But it proved to be enough, in terms of flexibility, to produce sounds from which one frequently couldn’t determine the original source. On my material you can hear this approach employed on such tracks as ‘Weathered Wall’ and the coda to ‘Brilliant Trees’ both from the album of the same name. On these songs, time was spent placing and occasionally repeating these unique elements to create motifs or meld together raw material into something that made sense within the context of the composition, but it was the beauty of the raw material that made this possible. After all, Holger himself would edit and rework his own material for extremely long durations. He frequently said the tracks or sketches he’d been working on would reach a stage in their development that necessitated their temporary retirement, at which time he’d file them away, "let them mature like wine", only later taking the tapes from the stacked shelves, bringing them into play. A means of forgetting context and content perhaps. Memories of evocations tied to uncertainties. I’m sure this is how some of the orchestral samples in both ‘Plight’ and ‘Premonition’ were created. He’d brought them out of the ‘wine cellar’, into the light, for just this purpose.

‘Premonition’ was and is presented as it was played – a layered performance, spontaneous composition. There’s no editing involved; it was a complete work come the end of the night we’d spent creating it. There were no references to genre spoken of throughout the recording. At this point in time, i feel the most relevant touchstone might be ‘Sculpting in Time’ by Andrei Tarkovsky for reasons I feel are obvious, which I’m sure you can glean for yourself.

The material isn’t in search of visual accompaniment. It provides all the ‘visuals’ needed via evocation. Nothing is absent. It’s living, has an earthy component at its core, a grounding, which couldn’t be conceptualized prior to its creation. It came about, as so many things do, via process. We spoke, naively, of its potential healing properties. Not a term I’d use at this point in my life but, around 10 years after its release I did receive a letter from a teacher of a class for the mentally handicapped who offered thanks for the album which he said was played on a daily basis when it was time for the class to take their positions on the floor, in a darkened room, and relax, rest. He said the music hadn’t failed to have the desired effect.

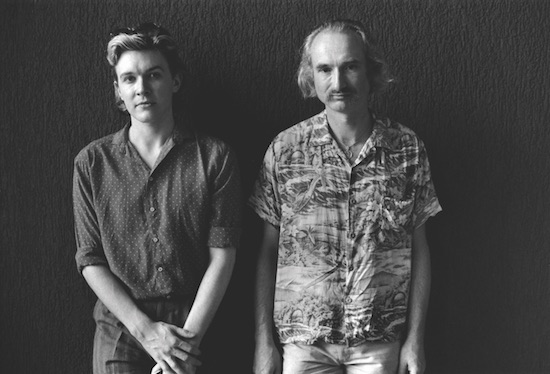

After a dispiriting solo tour in 1988 I returned to Köln to record a follow up to the previous release. It would’ve been futile to try and recreate the same set of circumstances that produced the first. Even the mood in the studio was markedly different from before. A new mixing console had been installed with an amenable, knowledgeable engineer, René Tinner, occasionally on hand. Even the lighting had changed, or so it seemed to me. Everything was brighter.

After the tour, I’d set up a system in my home in London where I’d play off of a looping sequence created on a Prophet VS, accompanying myself on guitar which I’d become more attached to as instrument of choice. I also set up a looping system, not so different from those used on the instrumental portion of ‘Gone To Earth’, which allowed me to build upon a seemingly ever ascending sequence of chords with solo lines upping the almost keening nature of the content.

Prior to setting off for Köln, i’d asked Holger to hire a VS just in case it might come in useful. I’d used the studio’s PPG on ‘Premonition’ and loved the results, but didn’t know how much more I could get out of the machine. I found Holger in predictably high spirits but these were aided and abetted by a temporary addiction to cocaine which, although I’d been clean for some time, I felt partially responsible for. Holger was witty, conversational, filled with anecdotes and jokes at the best of times (he claimed he’d discovered a sense of humour at aged 40) but on the drug the chatter was ramped up to the point where little work was getting accomplished. At one point I plugged in the VS and my guitar and just started to cycle around the patterns I’d been using to help me meditate or lose myself in for periods of time. Again, Holger had the multitracks in record without my being aware of it. At the end of the cycle he said, "perfect, let’s start from here". We began to think about a pulse for the piece and Jaki, who’d often drop into the studio, was asked to supply something appropriate. He played a high pitched, handheld drum. I found the pitch to be problematic and so lowered it with the aid of a harmonizer. More overdubs were created but the process felt less uninhibited than on our previous venture. We were ‘composing’ the work with, what I guess one could describe as, fully consciousness faculties at work; self editing, second guessing. But this wasn’t outperforming the virtual somnambulistic, trance-like, creation of our prior work. Michael Karoli dropped in and added guitar to Flux, and later still, Marcus Stockhausen, who seemed bemused that so little was being asked of him as a performer "No Marcus, you’re playing too much harmonic variation with unnecessary expressiveness…” but who was gracious and humble throughout.

It wasn’t an easy work to mix. I now wish Holger had been left alone with it, to go to town on the material in the way he had with ‘Plight’. I’m not sure he was in the right frame of mind to do so but I believe that, given time, he’d have wielded a greater magic. I anticipate there being attempts buried someplace in his archive.

Once again, I found standing centre studio playing guitar, looping fragments, accompanying myself, creating a mood of comfort and yearning as was my inclination at the time. Again, the machines were rolling. I asked to record numerous overdubs of single guitar lines at the end of which Holger suggested we invite Jaki back in to add some flute which appears at the opening of what became ‘Mutability’. That’s all that constitutes the track, completed and mixed as it stood with the hum from the guitars pickups resulting from the poor grounding of the studio setup. "What shall we do about the buzz and hum from the pickups?” “What buzz and hum. Oh that? I like it” . The sessions, unlike those for P&P, had a little proved exhausting. A certain lack of focus, the constant banter, took its toll. I wasn’t certain we’d achieved what we’d set out to. Once mastered I never listened to the album again so my recollection here in terms of content might be a little faulty. However, I’d been intrigued by this notion of spontaneous composition and began to wonder how I could pursue this notion further with a larger grouping. Not long after, I formed Rain Tree Crow.

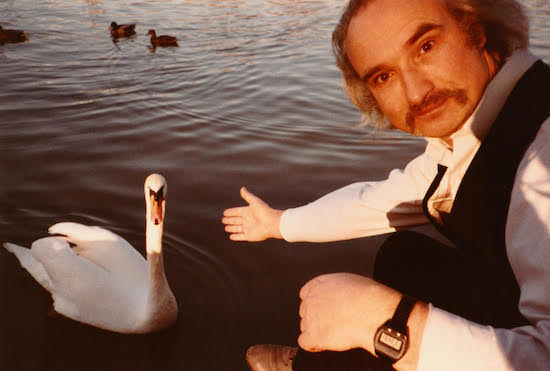

Holger was spontaneous, excitable and enthusiastic. His humour was usually very good, high spirited, unless he’d felt a slight from someone regarding the business aspect of his relations with others. A individual might be ostracized, the reasons for which they might never fully fathom. Holger was supremely surefooted but generous in his approach. The studio was his home and he knew it as intimately as if it were an extension of his own body and senses. He had a somewhat playful relationship with Jaki ("He’s always told me I was the worst person to play with, that I had no idea how to play bass. But I love to wind him up, it’s how you get the best out of him once he reaches a point of utter frustration”). We both knew relatively little of one another’s backgrounds. There’s few people I loved more than Holger and I’m not talking about his role in my life as musician or collaborator. He blossomed with an attentive audience and I was a good listener. The stories came fast and furious. Some involving the supernatural, others, his time in Can and, in particular, the period post Can where he’d suffered something akin to a nervous breakdown which eventually led to his rebirth as the man we remember today. I’ve never liked the ‘mad genius’ tags attached to him. He played up the buffoonish image for reasons of entertainment and self amusement but there was an acute sensibility at work as sober as any i’ve witnessed. Up until his marriage, his entire focus was on the creation of new, groundbreaking work. The melding together of the most unlikely elements was a challenge he couldn’t resist. The results tickled him and he’d giggle with characteristic playfulness as he’d share the results with others. The degree of insightfulness, musical knowledge, and hours of labour that went into creating the material was downplayed.

Plight & Premonition is one of the few works I’ve been creatively involved in that I could return to and objectively enjoy as listener. I found I had greater success in creating something, not of a similar nature, but born of a similar inclination with building a sense of nonlinear narrative born of the influence of film, musique concrete, and an admiration for the foley artist with ‘When loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima’, and more recently, ‘Playing The Schoolhouse’. These are direct descendants of what was unearthed over a period of two nights, animated by a primal spirit, in a converted cinema on the outskirts of Köln, over thirty odd years ago.