Films about exorcisms suffer from much the same problem as any movie in which the antagonist is a shark. Try as they might, such pictures can never seem to surpass a milestone moment in cinema; one that nailed the genre back in the 1970s and to which any subsequent toothy venture will be inevitably and unfavourably compared. Whereas special effects have evolved since the making of Jaws with its lumbering plastic sea creature, that movie’s pace, tension, music, atmosphere, cinematography, characters and script, in all likelihood, cannot be bettered.

The same goes for anything that dares to follow in the smouldering hoofprints of The Exorcist. Filmmakers keep churning them out, regardless. Sometimes the footage is grainier or the action gorier. The budget might be on the higher side or the lower. Rarely do these efforts add many fresh ideas to the well-worn yet presumably bankable formula. The fact that each attempt has such a similar storyline to the last could be part of their appeal. What do people find comfort in? Religion and routine. Familiarity, too, when it is not breeding comtempt. Viewers of exorcism films should know that their expectations are not going to be challenged any more than their faith or lack of.

A young girl is possessed by The Devil or else one of his diabolic helpers. Maybe the child is making it up! It could be she’s just gone a little bit loopy. (Spoiler alert: she hasn’t. People can’t levitate in real life or survive rotating their head like a featherless owl no matter how mentally frustrated they are at the time.) More often than not, the audience is informed via the opening credits that the events are “based on a true story” because humanity has the long and inexcusable tradition of conducting these purification rituals in real life despite the fact that demonic possession has never actually existed.

A priest or two will be enlisted to rid the poor girl of her scourge. One or more of these collared heroes will have lost their belief in God or be questioning it. The girl’s behaviour will gradually worsen from pretty creepy to a level that’s unintentionally comical, especially to sceptical viewers, leading to a completely over-the-top third act in which all hell breaks loose, almost literally. She floats several feet above the bed. Her contortions are accompanied by snapped celery sound effects. She breaks through her restraints with superhuman strength. There is some blood and a lot of swearing. The actress’s voice will now be dubbed by a male actor. There’s manky skin. Horn growth, sometimes. Vomiting galore. Eventually, the demon is cast out of its host. Or is it? No! Because a sequel beckons.

On a personal note, although I admire the set pieces in 1973’s The Exorcist, I never found them to be particularly scary. There are a few reasons for this. For one thing, I didn’t grow up in a religious household and we never went to church so demonic possession has never been high on my long list of major fears. I can’t remember at what age I first saw the film but I must have been already too old and cynical for it to fully freak me out. What’s more, it had been referenced so often in popular culture that its shocks were not new to me. The power of parody to puncture the pomposity of serious works seems particularly potent when one is exposed to the spoof version before its source material. Once you’ve seen Dawn French puke pea soup into the eyes of an irritated Jennifer Saunders, that’s all you can think about when Regan MacNeil or one of her many facsimiles does the same to a man of the cloth. Alas, sketches such as that one did nothing to curb the genre.

Fast-forward through decades of largely lacklustre rip-offs to 2023 when Linda Blair returned as MacNeil in The Exorcist: Believer. The narrative centres around a couple of possessed girls this time, instead of one individual. As far as innovative thinking goes, that’s up there with Look Who’s Talking Too.

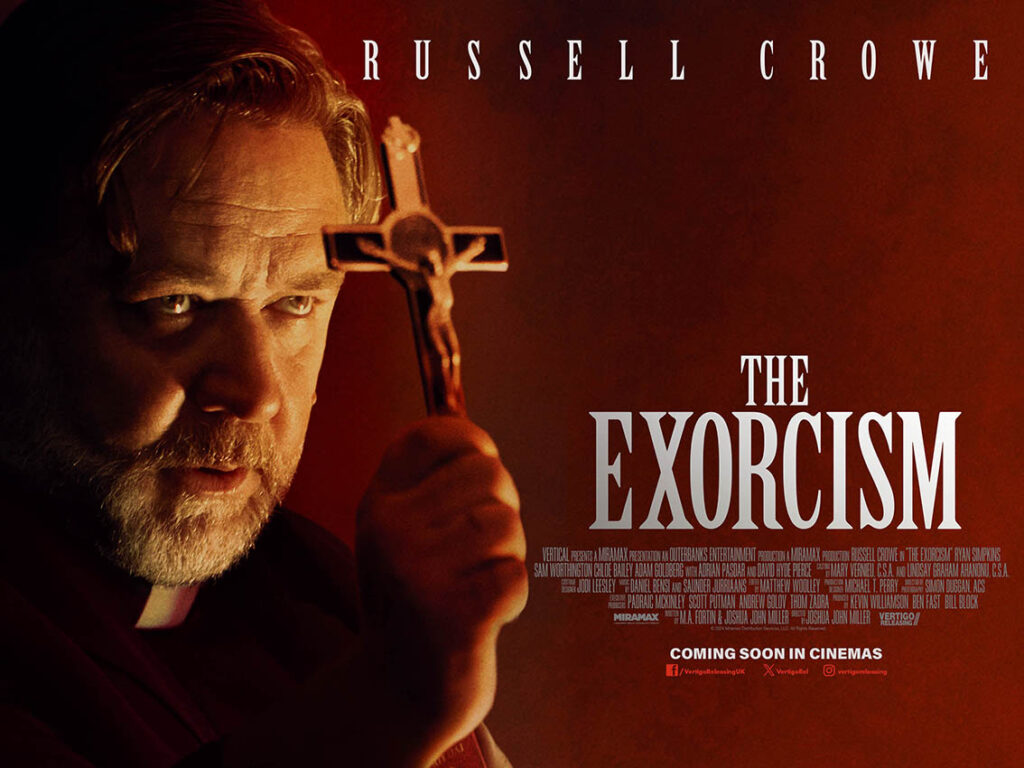

Step up, then, Russell Crowe, who’s lately developed a penchant for these kinds of movies. (Well, it could be the malevolent entity that’s pulling the actor’s strings. In industry terms, they’re known as an “agent”.) Although its filming was completed first, The Exorcism‘s release follows last year’s The Pope’s Exorcist in which Crowe played Father Gabriele Amorth (1925–2016), the non-fictional performer of over 50,000 exorcisms or, as non-believers would call him, a completely shameless fraud. In Crowe’s twinkle-eyed portrayal, Amorth is a wise-cracking, hipflask slugging and Lambretta riding enemy of Satan whose accent regularly matches that of the puppet “Papa” from the “Dolmio Family” advertisement campaign. A sequel has been greenlit.

Not related to that or any other film-cum-franchise, The Exorcism offers two variations on the theme of its unimaginative title. It has a vaguely postmodern quality in that its story takes place during the making of a horror film. This touches on the notion that the set of William Friedkin’s original The Exorcist was cursed. Funny how a hex is never diagnosed when someone injures themselves during a stunt on Spy Kids 2 or dies shortly after wrapping a film about wisecracking anthropomorphic bears.

The Exorcism‘s director and co-writer is Joshua John Miller. He is the son of Jason Miller, who played Father Damien Karras in The Exorcist, so perhaps some repeated family anecdotes are being drawn on here. Even so, the people behind the Scream franchise would have had added more fun and wit to the idea, given their knack for making self-referential movies that don’t quite tumble into full lampoon.

Crowe plays the world weary Anthony Miller, an actor cast to replace another man who died in the middle of filming a picture that looks very much like The Exorcist. Miller has unresolved traumas, both recent and distant, and has been to rehab for drug and alcohol issues. He is also trying to reconnect with his estranged teenage daughter (Ryan Simpkins). This is where the second interesting, if not exactly revolutionary, idea comes in.

Basically, The Exorcism inverts the traditional dynamic of a parent being concerned about their possessed child. The original trope has long been interpreted as a metaphor for puberty. In place of their precious little darling, families are suddenly confronted by a newly unrecognisable and ungrateful so-and-so who swears at them, vomits, bleeds, expresses sexual desire and is driven by other strange and irrational-seeming impulses. Instead of offering any support or empathy to the adolescent in question at this difficult time in their teen or preteen life, a Catholic priest is hired to hurl holy water around the bedroom and shout Bible passages into their greasy face.

In The Exorcism, however, it is the child who has to fret about her father. This film arrives at a time when it has been reported that young people, for at least once in modern history, are behaving more sensibly than older generations did and their elders often still do. It’s obviously a generalisation, but there are reports that younger people don’t drink as excessively these days. Many eschew nightclubs, for better or worse, preferring to stay in with Netflix and a pot of herbal tea. Recreational drug use is also down. (At one point in this movie, Simpkins takes the tiniest toke of a small spliff, out of politeness. Then it’s back to the business of keeping an eye on dishevelled Dad.) How novel that the kidz might be concerned with their personal health as well as that of the planet; a whole generation tutting like Saffy from Ab Fab at the embarrassing indignity and selfish sight of their elders, as well they ought.

Only this week did I witness a group of lads alight a train at gone midnight. Not the most typical sight on late-night British public transport, they took care to sweep their cans of lager (or possibly fizzy pop) off the four-person table and immediately place these in the bin on the station platform, saving the carriage crew a thankless job and proving themselves to be responsible and upstanding citizens.

Speaking of which, I’d just been to see Fat White Family in Leeds. Frustrated by incessant audience requests for ‘Cream Of The Young’, singer Lias Saoudi impatiently explained that most of his current lineup didn’t play on the early material. “They keep getting younger…” he noted, paraphrasing David Wooderson’s love of high school girls in Dazed And Confused. At this point it struck me that the band itself is tighter, more skilful, less shambolic and, dare I say it, more sensible than it’s ever been or sounded before. Then again, it’s easy to look relatively sensible when you’re accompanying a frontperson who’s got a loaf of bread wedged into the crotch of his ladies’ Spanx.

Anyway, after Crowe’s character is found sleepwalking in a trance, his behaviour escalates along the lines viewers would expect. Is he unravelling because he’s not taking his meds and is back on the bottle? Is he taking the Stanislavski system to outrageous extremes? Does he need a cuddle? Therapy? Or is something more supernatural occurring? Take a stab in the dark. And it will be dark because we’re all familiar with the Devil’s unbreakable hold over light switches. Needless to say, there is also a priest on the set of this film whose tasks quickly begin to exceed those listed in his job description as a religious consultant. When Crowe starts spitting out the inevitable expletives in a deeper voice than his character’s daughter is used to hearing, it’s much more laughable than frightening.

That said, you do feel for Crowe’s character because he doesn’t need to be put through this palaver at his ripe age. Unlike some of the fresher faced heroines who’ve littered films such as this, when Miller’s bones are bent backwards you don’t think, oh well, he’ll be all right after a run around the park and upping the calcium intake. This poor fellow’s got a lifetime of chiropractor appointments ahead of him. If he survives his fiendish ordeal, I might add.

The Exorcism is commendable for trying to do something slightly different with this hackneyed format, even if this isn’t pushed far enough to avoid the usual clichés and predictability. Clearly this isn’t the final word on scabby possession and not even the last we’ve seen of Russell Crowe flogging the dead horse of bedevilment. To quote the demon Asmodeus from The Pope’s Exorcist, who continues to taunt Father Amorth as the final act is dragging on and cinemagoers have already waited long enough to release their bloated bladders, “We’re not done yet.”

The Exorcism is on general release today