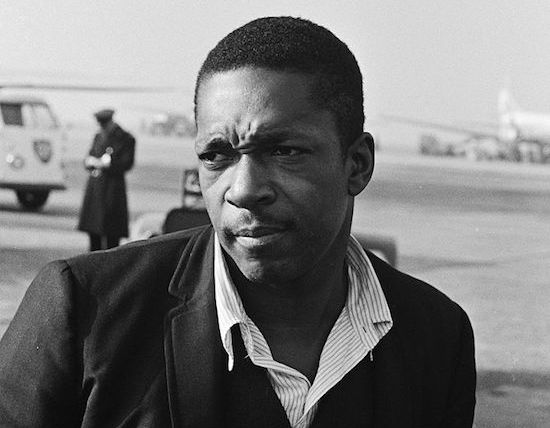

John Coltrane at Amsterdam airport, October 1963 (Hugo Van Gelderen/Dutch National Archive)

It might seem the obvious question no one is asking about this recently rediscovered March 1963 session by the iconic saxophonist: how can a major label lose a John Coltrane record? The answer helps us understand not just the story behind this formidable music, but also the hidden ways John Coltrane reshaped the jazz aesthetics of his era.

The surprising truth is that Coltrane was running a kind of subversive secret society within his own label, Impulse! Records. “My contribution with Trane was to let him record whenever he wanted,” his record producer Bob Thiele later admitted. “Even when the corporate power structure was opposed to it.”

“I believe his contract called for two albums a year to be recorded and released,” Thiele explained. But that wasn’t how John Coltrane operated. He saw every day as an opportunity to advance his musical vision another notch, expand his range of expression, and maybe even record some tracks. “I was always brought on the carpet,” Thiele said. “They couldn’t understand why I was spending the money to record Coltrane, since we couldn’t possibly release all the records we were making… It reached a point where I would record late at night so at least we’d have peace then, and no one in the company would know where I was.”

So you shouldn’t be surprised that label execs at Impulse! could lose an entire album. They probably had no clue it existed even back in 1963. Today, they brag about their rediscovery. But they really ought to do penance at the Church of John Coltrane (yes, that alternative denomination actually exists in San Francisco) for all the obstacles they put in the saxophonist’s way. This remarkable album, Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album, exists today despite Coltrane’s corporate overseers, not because of them.

The background details also guide us in assessing these rediscovered tracks. We need to remember that Coltrane wasn’t thinking about an audience, fifty-five years later, dissecting his music. He probably wasn’t thinking about the audience of 1963. He apparently didn’t even take time to give a name to the most significant tracks here, new compositions that will now be forever burdened with the unfortunate designations ‘Untitled Original 11383’ and ‘Untitled Original 11386’. Coltrane was merely living in the moment. That was, after all, what he did best.

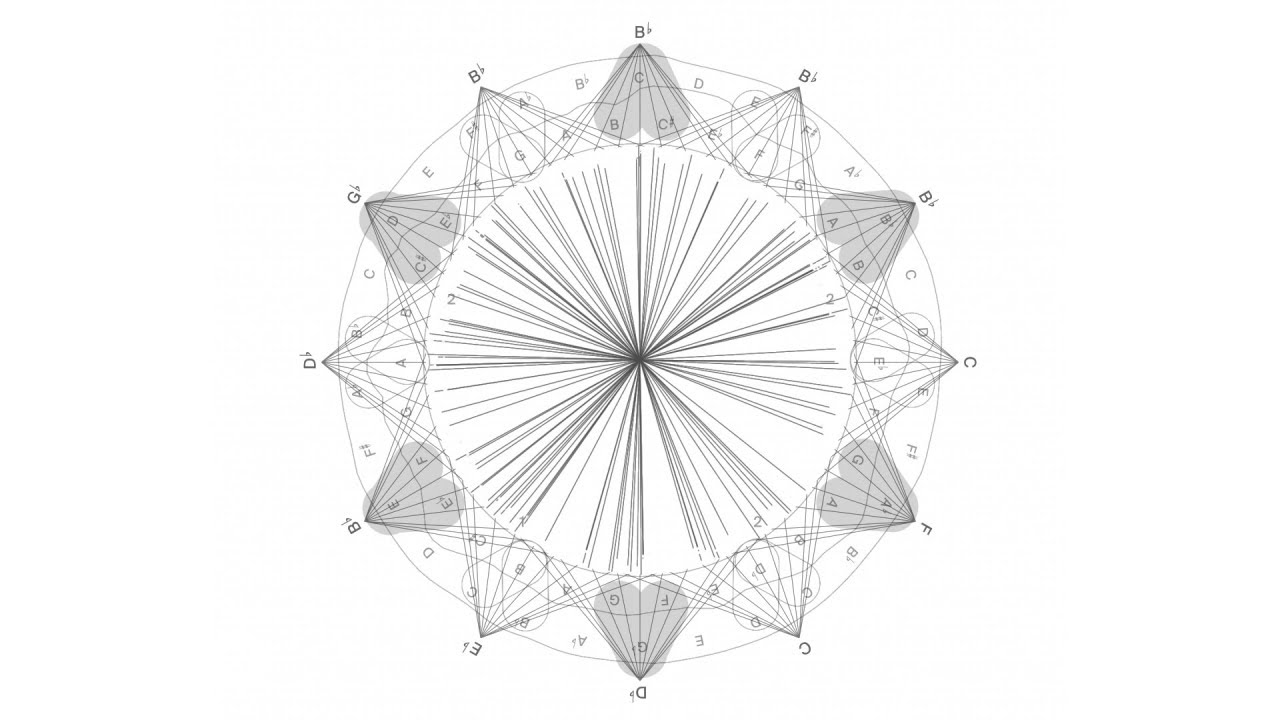

The first new composition, which opens our ‘lost’ album, is simply a twelve-bar blues. But nothing is really simple in the universe of John Coltrane, and from the start he pushes outside the typical constraints of that traditional idiom. What sounds like a solo sax intro is actually the opening of the blues form, and the arrival of the rest of the band at the end of bar two is a jarring surprise – who plays blues like that? But pianist McCoy Tyner knows what the boss likes, and immediately starts pushing the blues chord changes in directions never envisioned by the Mississippi Delta pioneers of the genre. And then – boom! – Tyner stops playing entirely, even as Coltrane hurdles onward through another two choruses. At this juncture you can hear hints of the motivic development of short patterns, turbocharged music memes, that would figure so prominently in this artist’s A Love Supreme 18 months later.

Coltrane’s solo on ‘Untitled Original 11386’, recorded that same day, features an even more adventurous soprano sax solo. Here the use of those same short motifs, with their rigorous logic, is juxtaposed with less tempered phrasing that keeps trying to escape across the border into a freer realm of shrieks and moans. It’s almost as if the Apollonian and Dionysian archetypes decided to go out together on a date, and this song is their naughty lovechild.

Other tracks here will be familiar to Coltrane fans. The version of ‘Nature Boy’ sounds fresh and prickly, but is less fully realised than the more rhapsodic version he would record in 1965. The saxophonist also serves up four different takes of his often-played ‘Impressions’, which matches modal chord changes from Miles Davis with a melody from symphonic composer Morton Gould. Coltrane had already recorded this work both live and in the studio, and these new versions won’t supplant the earlier versions. But take 3, which leaves out the piano, helps us grasp how Coltrane, at this juncture, was starting to view chord-driven accompaniment as a limitation as much as a support.

Perhaps the biggest surprise here is the appearance of ‘Vilia’, from Franz Lehár’s 1905 operetta The Merry Widow. This is about as light as light opera gets, but maybe Coltrane had been listening to the 1963 Columbia release of the work or remembered Jeanette MacDonald singing the piece in the sentimental 1934 movie version of Lehár’s work. The whole band behave decorously here, and show surprising respect for the chord changes. This track is a good reminder that Coltrane was at a crossroads during this period, pushing ahead into uncharted territories but also willing to take a pop culture tune and play it relatively straight, much as jazz musicians had been doing for decades.

Perhaps that’s why the label decided to give the title ‘Both Directions at Once’ to this newly discovered project. That’s what this album represents: a look back at the tradition and a push forward into uncharted territory. Coltrane was always a moving target – critics during his lifetime would try to assess what he was doing but before the ink dried on their reviews, he would have advanced into the next phase of his ever-evolving career. We can now grab hold of this moment from 1963 and savour it. But Coltrane himself would never have done that. For us, it’s a masterpiece; for him, just another day’s work.

Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album is out this week on Impulse!. Ted Gioia is the author of ten books, including The History of Jazz, Delta Blues and Love Songs: The Hidden History. His most recent book is How to Listen to Jazz from Basic Books