Bruce Springsteen was never a punk. He was too good for punk, not in the sense that he was too skilled an instrumentalist or too talented a songwriter. He was too good for punk because he didn’t want to shock. He didn’t take drugs, he barely drank, and he was interested in rock & roll as a force to bring people together, not divide them. For all that he would indulge in long onstage monologues about his fractious relationship with his father, Springsteen was no one’s idea of a son to be ashamed of. Quite the opposite: he was sober, diligent, driven. He respected his elders, even if those elders were Elvis and Otis Redding and Mitch Ryder, rather than the fellas at the factory.

But punk intrigued Springsteen. Of all the major American stars making records in the prepunk age, he had the closest relationship to it. He shared some of its impulses – to simplify, to democratise – and he admired its musical directness, which reminded him of the effect rock & roll had on him as a kid. "I loved those early Buzzcocks records, all the Clash records, the singles – because you couldn’t get the records you had to try to go and get the singles," he told Elvis Costello for the TV show Spectacle in 2009. And he was fascinated with the musicians of punk: with Lou Reed, with Suicide, with Patti Smith, with the Ramones.

You might not have been able always to hear that fascination in his songs – the idea that ‘Hungry Heart’ was earmarked for the Ramones until Jon Landau told Springsteen to keep it is baffling not for the fact of Springsteen writing for the Ramones, but because the idea of Joey Ramone singing of that lyric set is impossible to compute. ‘Hungry Heart’ sounds no more like a Ramones song than ‘Hungry Like The Wolf’ does – but it was there, and there were ways it emerged in his music, and in others’, a generation down the line.

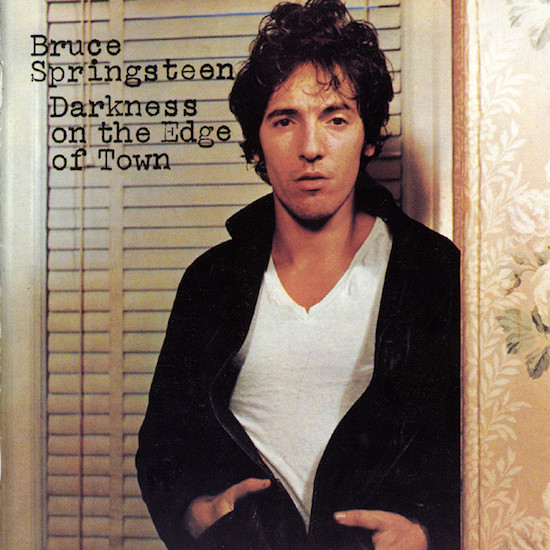

The "punk" Springsteen album, logically, is Darkness On The Edge Of Town, released on 2 June 1978. In the three years since Born To Run had finally broken him as a major artist, he had been forced into silence as he tried to extricate himself from his contract with his manager Mike Appel, and had watched and listened as music changed around him. And as he recorded Darkness, between October 1977 and March 1978, the ferment captivated him.

"Out went anything that smacked of frivolity of nostalgia," he wrote in his autobiography, Born To Run. "The punk revolution had hit and there was some hard music coming out of England … Pop needed new provocations and new responses. In ’78 I felt a distant kinship to these groups, to the class consciousness, the anger. They hardened my resolve. I would take my own route, but the punks were frightening, inspirational and challenging to American musicians. Their energy and influence can be found buried in the subtext of Darkness On The Edge Of Town."

It’s not so much the subtext, as the text. The songs on Darkness displayed a completely new way of writing for Springsteen. Gone were the self-mythologising street epics, in which 357 characters with ridiculous nicknames go off on wild goose chases around the Jersey shore (in fact, shaggy dog poetry was never again to be part of Springsteen’s MO). Instead, these were taut, compact songs, designed to to amuse and amaze, but to pummel at real emotions. You would never mistake them for "punk" songs, because the emotions are more complex than any of the punk writers were yet approaching (ambivalence and ambiguity, the enemies of punk’s bald statements, were constants on Darkness On The Edge Of Town). The emotions are complex because Springsteen’s background was that of the people he sang about: poor, prospectless and uneducated, in a place where arguments might well be settled with fists. In Born To Run he describes the memories that fed into the songs on Darkness: "I never saw a man leave a house in a jacket and tie unless it was Sunday or he was in trouble. If you came knocking at our door with a suit on, you were immediately under suspicion." And there was the abusive relationship next door. "He beat his wife and you could hear it happening at night. The next day you’d see her bruises. Nobody called the cops, nobody said anything, nobody did anything." This was not the world of the art school kids, the diplomat’s sons, the painter’s sons, that so much of punk was. Where bored suburbanite middle-class kids imagined their empathy for dead end lives, Springsteen felt it, because without rock & roll he would have had that life, whereas Joe Strummer or Billy Idol or Ari Up or Siouxsie Sioux almost certainly wouldn’t.

Throughout the album, Springsteen’s protagonists are filled with rage and confusion at their circumstances – be those circumstances their jobs, their relationships, their own inability to make adulthood work for them (unlike so much punk, this was grown-up music, not teenage music). These are people "caught in a crossfire that I don’t understand" (‘Badlands’), who "inherit the sins … inherit the flames" (‘Adam Raised A Cain’), who "tear into the guts of something in the night" (‘Something In The Night’). In ‘The Promised Land’, Springsteen lays down in just four lines – in a song about a kid pumping gas in a nowhere Utah town – what was the entire premise of punk: "Sometimes I feel so weak I just want to explode / Explode and tear this whole town apart / Take a knife and cut this pain from my heart / Find somebody itching for something to start." I find it hard to read that without picturing the teenaged John Lydon in his bedroom in Finsbury Park waiting for the chance to detonate in public, to throw shards of emotional shrapnel into the faces of the millions of people to whom people like him had no worth.

On the album’s most musically violent moment, ‘Candy’s Room’, Springsteen – not always, if we are honest, a great writer about desire – flung himself into sexuality with a startling fervour. And in the subject of the narrator’s affections – a prostitute – there’s punk’s dalliance with transgression brought into heartland rock, but with a tenderness and adoration that punk would have struggled with, and in the moment of ecstatic musical release there’s a line that sounds as though the Springsteen was engaged with a dialogue with the musicians who were telling him that there could be more to his music than Van Morrison and Bob Dylan and Stax and Hank Williams: "She says, ‘Baby if you want to be wild / You got a lot to learn /Close your eyes, let them melt / Let them fire, let them burn / ‘Cause in the darkness there’ll be hidden words that shine."

Punk cast its shadow over Springsteen through 1978 and the subsequent years. There was ‘Because The Night’, the half-finished song he decided to leave off the album, and which his engineer Jimmy Iovine thought was too good to leave on the studio floor, and so gave to Patti Smith, who was also recording Easter at The Record Plant in New York at the time. There was ‘Hungry Heart’, even if the Ramones never recorded it. There was his monologue on Lou Reed’s ‘Street Hassle’. And there was Suicide, who would become a thread that unfolded through Springsteen’s subsequent career ("You know, if Elvis came back from the dead, I think he would sound like Alan Vega," he told Mojo‘s Phil Sutcliffe in 2006).

You can hear Suicide, of course, in the cover of ‘Dream Baby Dream’ that became a Springsteen live staple in solo shows (a 2005 recording became Springsteen’s unlikeliest release: a 10" single on Blast First Petite), and you can hear it in the haunted, strangulated yelps on ‘State Trooper’, from Nebraska. You can hear punk in the way that primitive rock & roll became an increasingly common staple in Springsteen recordings from 1978 onwards, even if the actual songs were often outtakes and castoffs that would only emerge on box sets and compilations. This was the door punk and Darkness On The Edge Of Town opened for Springsteen: the realisation that directness and brevity could be virtues.

It doesn’t seem at all remarkable now to observe the conjunctions between Springsteen and punk. But when I first started listening to independent music, in the mid-1980s, it did. That was when Springsteen was at his imperial pomp, filling stadiums, and nothing could seem quite so far removed from the immediacy of punk as his bombast. Yet this Springsteen, the Spokesperson For The Ordinary Man (And Sometimes Woman), was winning admirers among kids who would become a different generation of punks, not in the big city scenes, but in the suburbs, in the flyover states – the kids who were divorced geographically from the promise of the lights and the clubs. These were the kids who were never going to be cool and whose bands were never going to be cool or press darlings (often, honestly, because they weren’t very good), and who made music for the same reason Springsteen did: because they wanted people to feel good about themselves. It was bands like the Hold Steady, the Bouncing Souls, Dropkick Murphys, Against Me!, the Menzingers, the reformed Social Distortion. It was especially, the Gaslight Anthem, whose singer Brian Fallon swallowed the Springsteen songbook so thoroughly he might as well have renamed his group the Emo Street Band. And Springsteen contacted and nurtured a great many of these young bands who idolised him, singing on their records, appearing at their shows.

And you can see the very things that Springsteen has long preached in the very foundations of punk practise: keep control of what you do; break down the barriers between yourselves and your audience; behave with integrity; support local causes; treat people with dignity. Above all, as he put it to me a couple of years back, displaying certain character traits: "dependability, strength, wilfulness… put in the service of something good". Which is why, perhaps, his journey through punk, starting with Darkness On The Edge Of Town, took him from Patti Smith and Suicide to the Dropkick Murphys and the Gaslight Anthem, rather than to, say, Liars. He wasn’t seeking the complication of the lives of the people in his songs, but the simplicity of redemption. Which is perhaps why ‘Dream Baby Dream’, not ‘Frankie Teardrop’, was the Suicide song that haunted him all those years.

Bruce Springsteen was never a punk. But there’s a lot of punk in Springsteen. And, in the right light and from the right angle, there’s a whole lot of Springsteen in punk.